MINNESHÄFTE, Peter Wrangels begravning, Belgrad 9 oktober 1929.

Rikt illustrerat. WRANGEL, PETER NIKOLAYEVICH

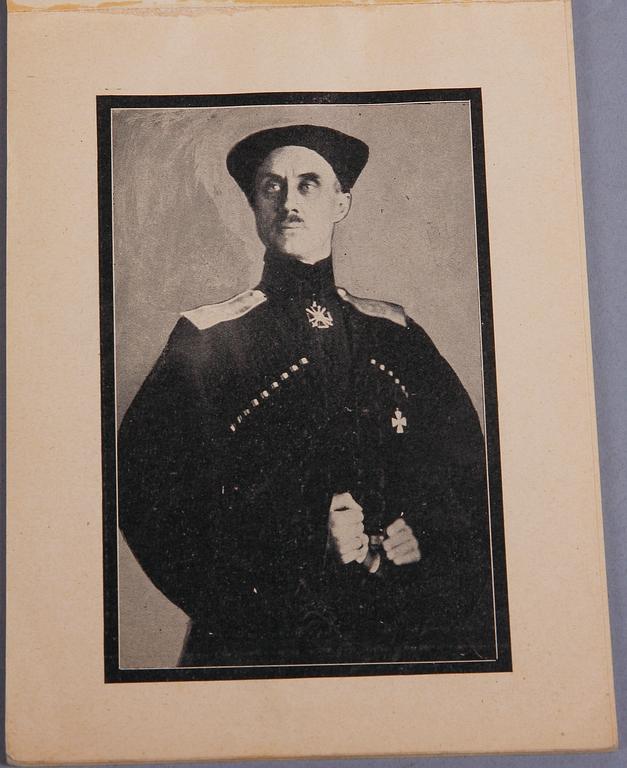

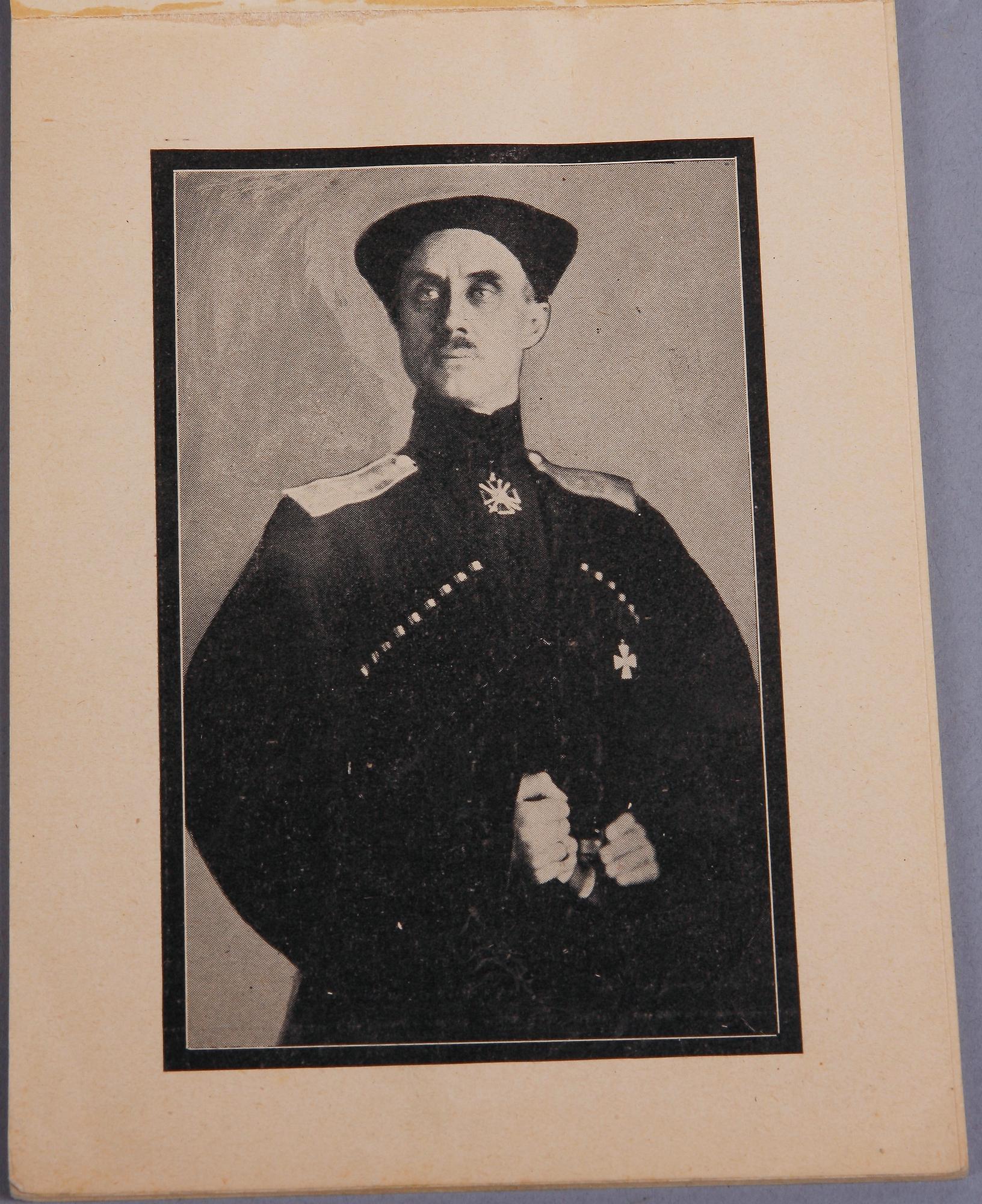

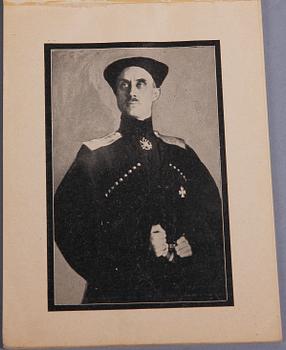

(1878–1928), general and commander-in-chief of the anti-Bolshevik forces in South Russia and leader of the White emigrant movement.

One of the most talented, determined, and charismatic of the anti-Bolshevik generals (and one of the few who was authentically—and unashamedly—aristocratic), Peter Wrangel was born in St. Petersburg into a Baltic family of Swedish origin. He graduated from the St. Petersburg Mining Institute in 1901, but then joined a cavalry regiment as a private before volunteering for service at the front during the Russo-Japanese War, where he served with a unit of the Trans-Baikal Cossacks. In 1910 he graduated from the General Staff Academy and in World War I commanded a cavalry corps. He took no significant part in the events of 1917, but after the October Revolution he went to Crimea, where he was arrested by local Bolsheviks and narrowly escaped execution. He joined General Mikhail Alexeyev's anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army in August 1918 and rose under General Denikin to command the Caucasian Army (largely made up of Kuban Cossacks) of the Armed Forces of South Russia. In that role he led a successful offensive against the Red Army on the Volga, capturing Tsaritsyn in July 1919. However, the haughty Wrangel never liked the plebian Denikin and, after a fierce quarrel with him over strategy during the Whites' Moscow offensive of the autumn of 1919, he was accused of conspiracy, dismissed, and exiled to Constantinople. Following the collapse of Denikin's efforts, Wrangel was recalled and found enough support among other senior generals to be chosen, in March 1920, to succeed Denikin as commander-in-chief of the White forces in South Russia, which were now largely confined to Crimea.

As a political leader, he was intolerant of opposition, distrusted all liberals, and remained a convinced monarchist, but he nevertheless promulgated a radical land reform in a belated attempt to win the support of the population (and the western Allies, who were by then despairing of the Whites). As commander, he was a strict disciplinarian, and he successfully reorganized the army (renaming it the Russian Army). However, a quarrel over command undermined a projected alliance with Pilsudski's Poland. Although Wrangel's forces managed during the summer of 1920 to pour out of Crimea into Northern Tauria, once the Bolsheviks had made peace with Poland in October, the Red Army was able to concentrate its vastly superior forces on the south and to drive the Russian Army back into Crimea. In November 1920 Wrangel organized a very remarkable and orderly evacuation of over 150,000 of his men and their dependents to Turkey, which was then under Allied control. They were poorly treated by the British administration of the Constantinople district and were subsequently scattered around Europe but remained unified through their shared experiences, their resentment of the Allies, and their veterans' organization, the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS), forged by Wrangel in 1924. Through ROVS Wrangel hoped to offer financial and social support to his men and to keep the émigré soldiers battle-ready and pure of political affiliation, while striving to unite monarchists and republicans under the banner of non-predetermination (i.e., by not prejudging issues regarding the future, post-Bolshevik, government of Russia). However, in November 1924, he announced his recognition of the claim to the Russian throne of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich. Wrangel died in Brussels in 1928, just as he and his associates were planning the creation of terrorist organizations to

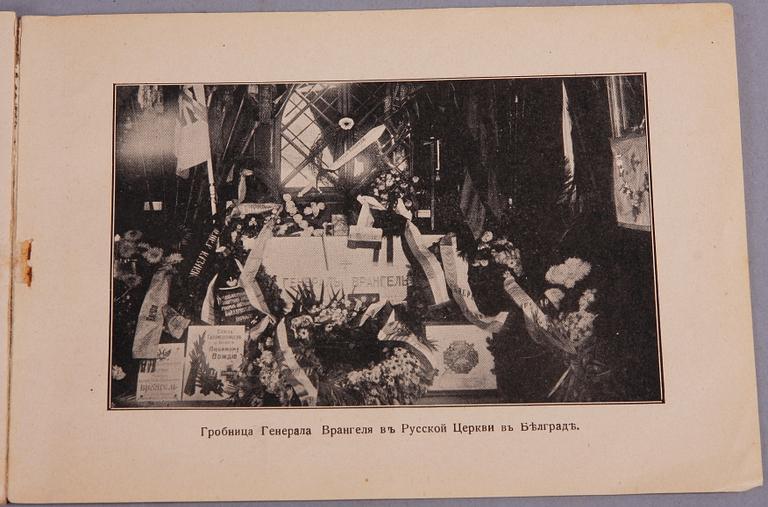

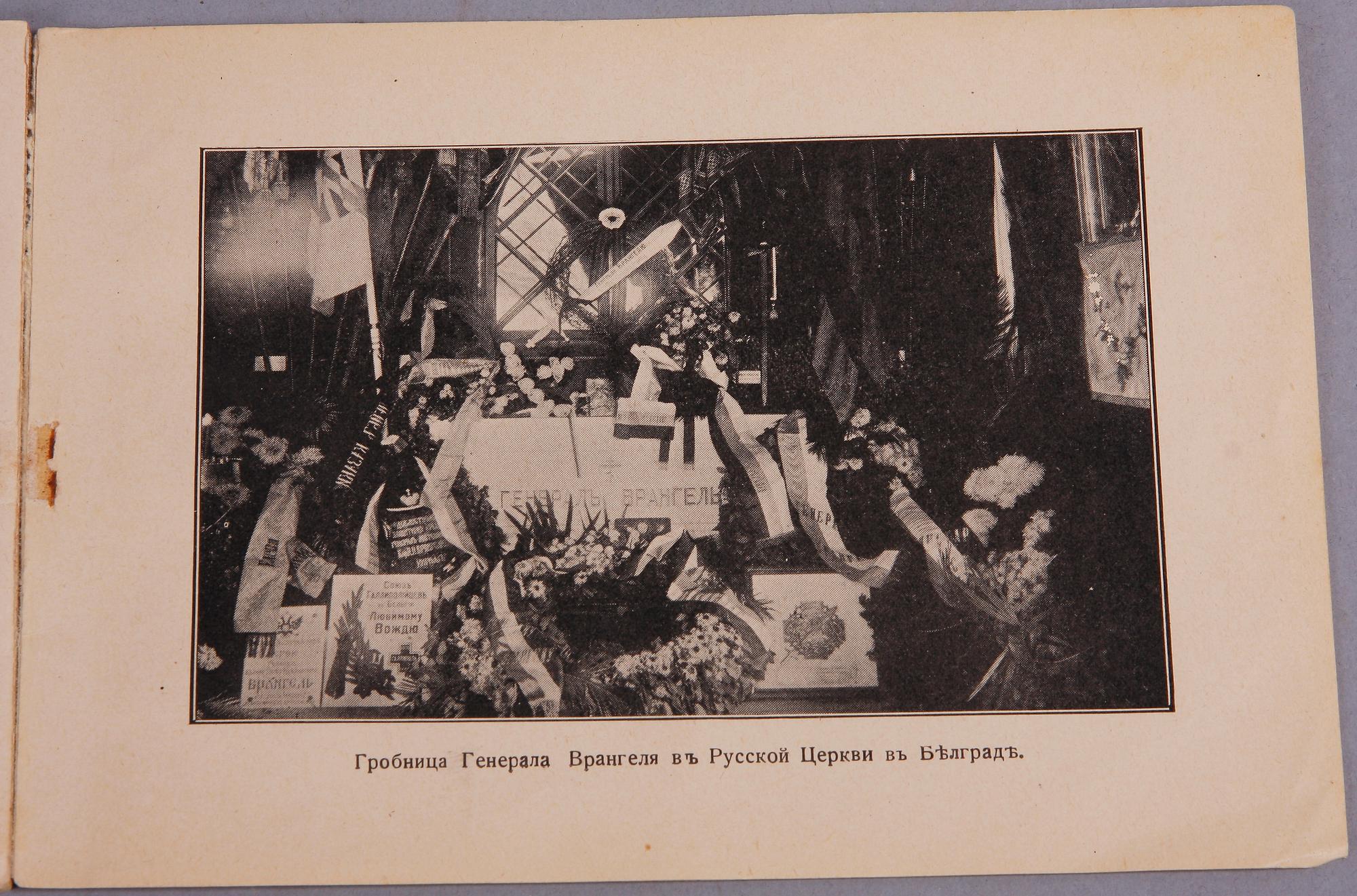

be sent into the USSR. His children believed he had been poisoned by the Soviet secret police. He is buried in the Russian Cathedral in Belgrade.

Slitage, smärre skador, fläckar.