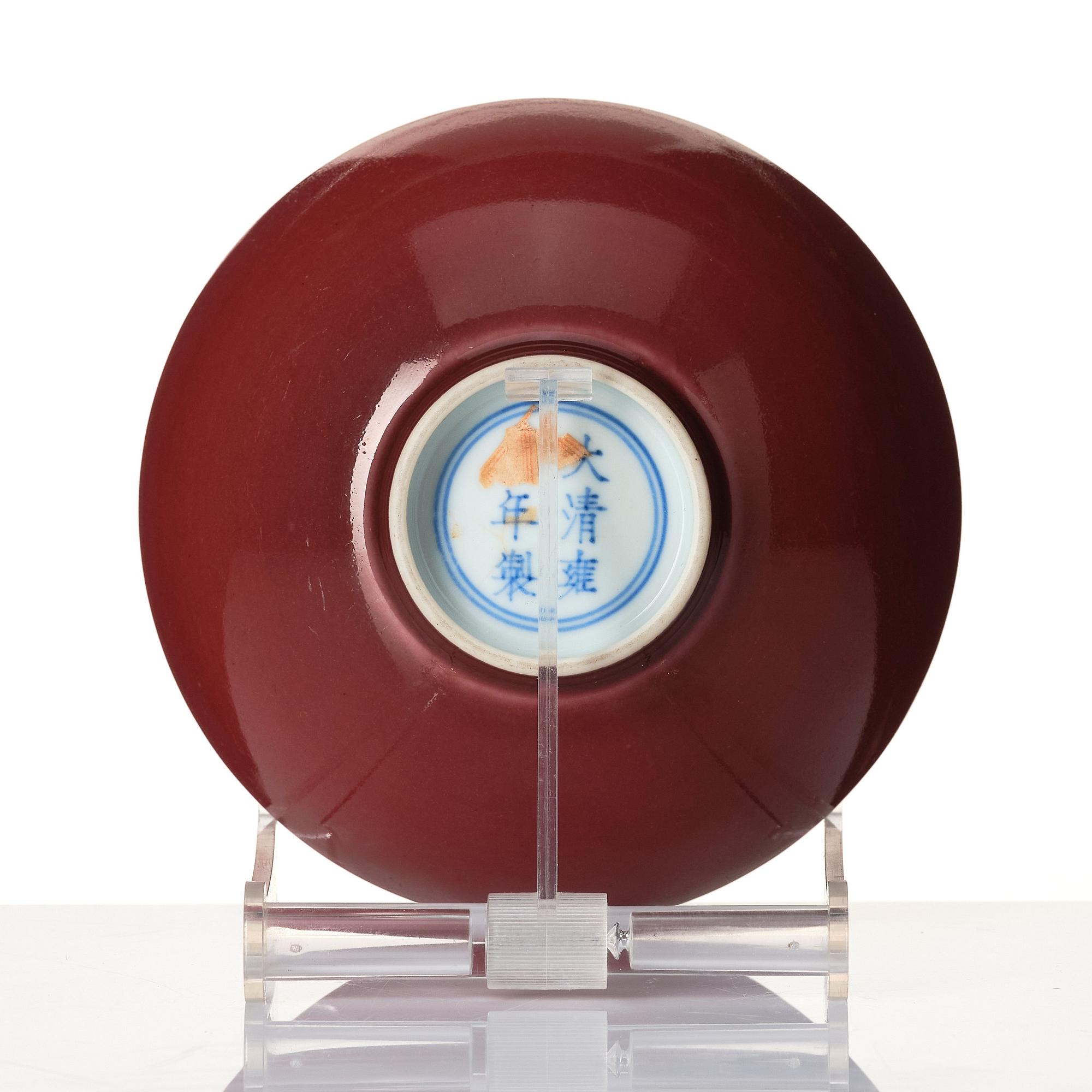

Skål, porslin. Qingdynastin, Yongzhengs märke och period (1723-35).

Djup med rundade sidor på en kort fot, exteriören glaserad i en djup kopparröd glasyr som övergår mot en vit kant vid fot och mynning. Undersidan med Yongzhengs märke i underglasyrblått inom dubbla ringar. Diameter 11,7 cm.

Spricka, slipad kant.

Proveniens

Gustaf Wallenberg (1863-1939) was Swedish businessman, diplomat and active politician. He was the son of André Oscar Wallenberg, founder of Stockholm Enskilda Bank (today SEB, and grandfather of Raoul Wallenberg (1912-47?). After a career in the Swedish Navy he turned to the business world and was very active in striving to better the transoceanic shipping industry. Something that came in handy when he in 1908 successfully negotiated with the Qing court in Beijing about a friendship, trade and navigation treaty. The collection was acquired between 1906 and 1918 when Wallenberg was the Swedish Envoy in Tokyo. From 1907 he was also accredited for Beijing and came to spend time in both countries as the Swedish Ambassador. Mr Wallenberg came to be in China in dramatic part of its history, when a lot of items came on the market and when the golden era of collecting Chinese works of art started in Europe.

It is visible in the communication that is kept at the Östasiatiska Museum in Stockholm that Gustaf Wallenberg and his good connections with the government came to mean a lot for all the Swedish engineers and businessmen who were in China at the time such as Johan Gunnar Andersson, Osvald Siren, Orvar Karlbeck, Erik Nordström and many more.

Bukowskis sold a part of this collection at Bukowskis Sale 554 in 2009 and Bukowskis Sale 556, 2010 as well as Bukowskis Sale 641, in 2022. These lots have remained with the family and are now offered at auction for the first time.

Övrig information

This bowl is notable for its vibrant copper-red glaze and its even tone which accentuates the graceful curves of its elegant form. A notoriously difficult pigment to fire, the use of copper was largely abandoned after the 15th century as the slightest irregularity in any stage of the production resulted in an undesirable and uneven color. Yet, with the technical advances made at the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen from the early Qing dynasty onwards, by the 18th century, potters were able to accomplish a previously unattained command over the pigment to successfully create a number of monochrome vessels with a strong and even red tone, such as the present bowl.