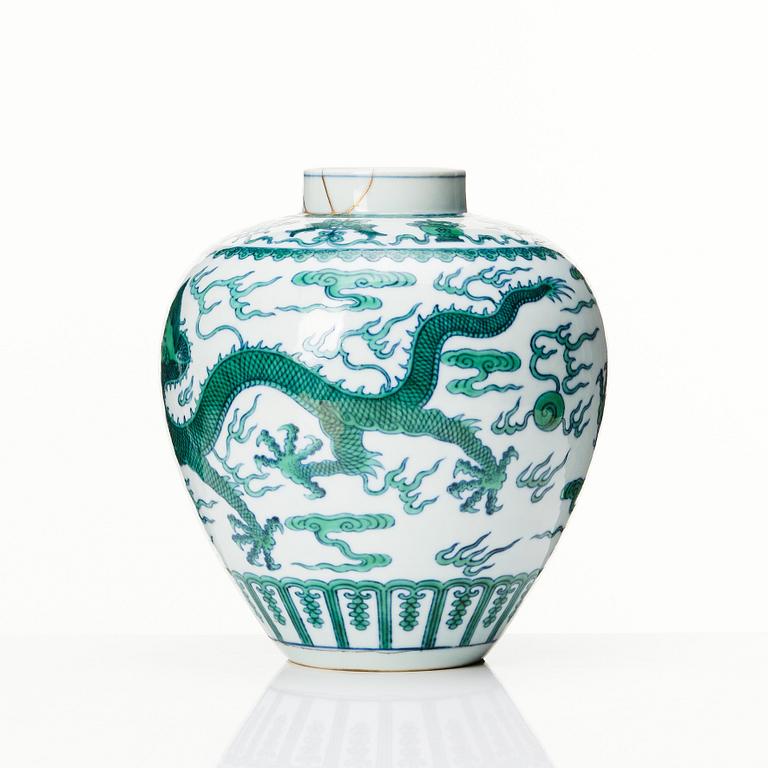

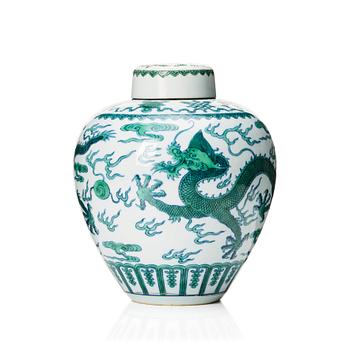

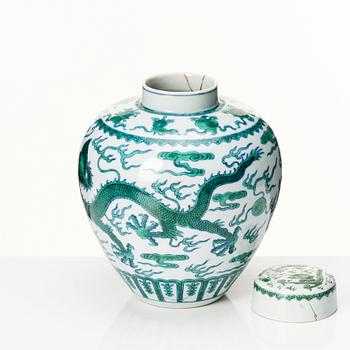

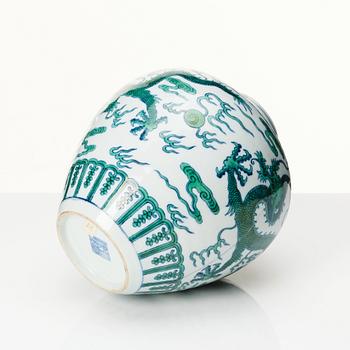

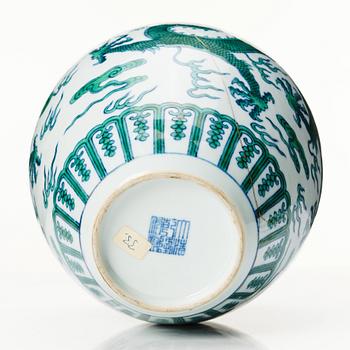

Urna med lock, porslin. Qing dynastin med Qianlongs märke och period (1736-95).

Rundad ovoid kropp med indragen fot och kort hals. Utsidan dekorerarad i grön emalj med femkloade drakar jagandes den flammande pärlan. På skuldran en ruyibård följt av de åtta buddhistiska emblemen s.k. bajixiang. Undersidan med Qianlongssigillmärke i underglasyrblått. Höjd 21,5 cm.

Lagad. Locket skiljer sig i glasyr.

Proveniens

From the Collection of Gustaf Wallenberg (1863-1939). Gustaf Wallenberg was a Swedish business man, diplomat and active politician. He was the son of André Oscar Wallenberg, founder of Stockholm Enskilda Bank (today SEB, and grandfather of Raoul Wallenberg (1912-47?). After a career in the Swedish Navy he turned to the business world and was very active in striving to better the transoceanic shipping industry. Something that came in handy when he in 1908 successfully negotiated with the Qing court in Beijing about a friendship, trade and navigation treaty. The collection was acquired between 1906 and 1918 when Wallenberg was the Swedish Envoyé in Tokyo. From 1907 he was also accredited for Beijing and came to spend time in both countries as the Swedish Ambassador. Mr Wallenberg came to be in China in dramatic part of its history, when a lot of items came on the market and when the golden era of collecting Chinese works of art started in Europe. Thence by descent.

Utställningar

Compare a Qianlong mark and period jar and cover, in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, published in Enamelled Ware of the Ch’ing Dynasty, vol. II, Hong Kong, 1957, pl. 13.

Compare another is included in Chinese Porcelain in the S.C. Ko Tianminlou Collection, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1987, cat. no. 114.

Several Qianlong jars with covers from private collections include one from the collection of Edward T. Chow, sold at Sothebys, 19th May 1981, lot 537; another from the W.W. Winkworth collection, illustrated in Soame Jenyns, Later Chinese Porcelain, London, 1951, pl. XCI, fig. 2, and sold twice at Sothebys, 29th November 1977, lot 128, and again, 1st November 1999

Litteratur

Imperial porcelain wares painted with vigorous dragons in green enamel against a white ground were first produced during the Chenghua period (r. 1465-87), and continued to be popular throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties. While in the Ming period dragons were generally incised and reserved in the biscuit, and after the first firing enameled in green and black, in the Qing dynasty the dragons are invariably painted over a layer of transparent glaze.

See a Kangxi prototype, from the Qing Court collection and still in Beijing, published in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, Hong Kong, 1999, pl. 190.

Bukowskis sold a part of this collection previously at Bukowskis Sale 554 in 2009 and Bukowskis Sale 556, 2010.

Övrig information

The pieces are repaired in Japan in a technique called Kintsugi (translates to ‘golden joinery’), also known as kintsukuroi ‘golden repair’. It is a Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending areas of breakage with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver or platinum, and it treats breakage and repair as a part of the history of an object rather than something to disguise.

One can clearly see in the academic collection of Gustaf Wallenberg, that he appreciated the items for their quality and the rareness of the pieces, and that he very confident and appreciated this way of taking care of the magnificent cultural heritage of China.