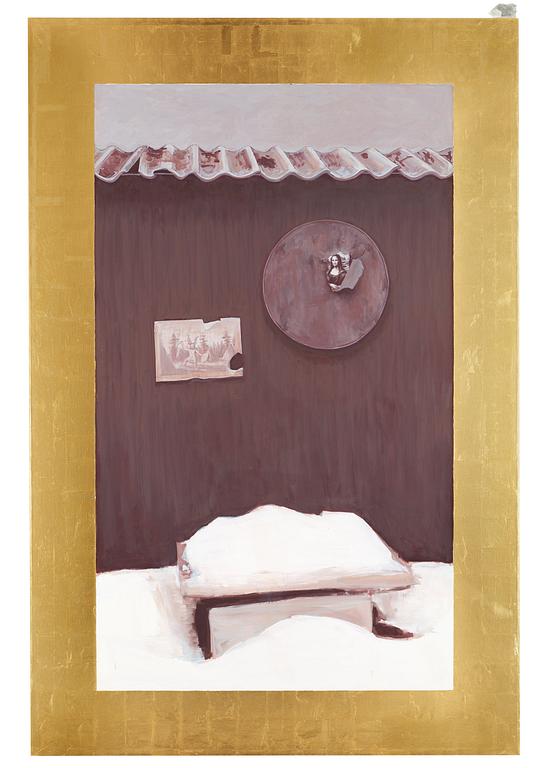

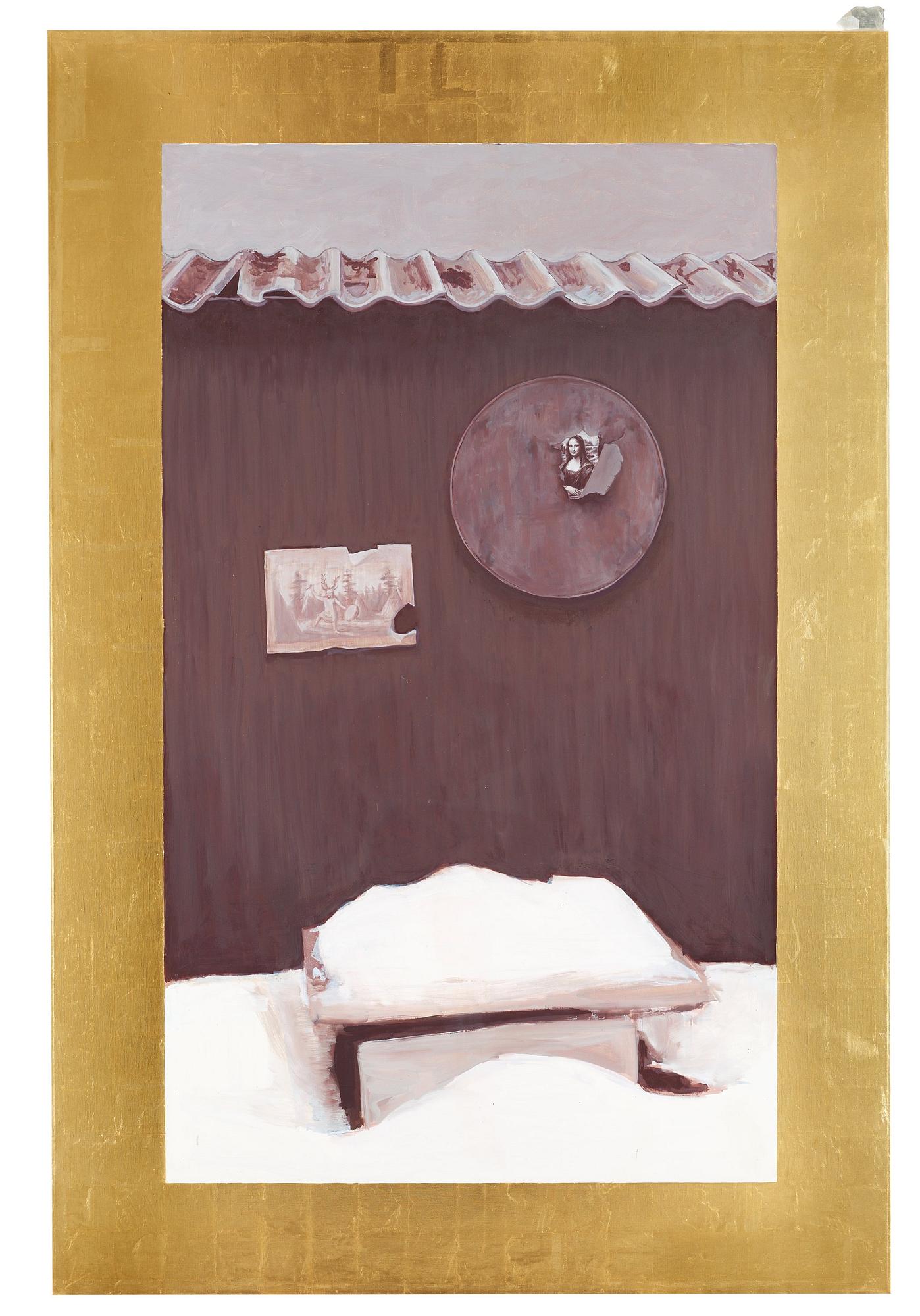

Ylva Snöfrid (Ogland)

"Loka med Mona Lisa nr 1"

Signerad Ylva Ogland och daterad 2003-2006 a tergo. Olja på duk med bladguld, 200 x 133 cm, med tillhörande bergskristall.

Proveniens

Galleri Brändström & Stene, Stockholm.

Privatsamling, Stockholm.

Utställningar

Galleri Brändström & Stene, Stockholm, "Loka/Ylva –85/Press Through", 30 mars - 30 april 2006.

Övrig information

NICOLA TREZZI ON YLVA OGLAND

Rooted in the language of painting, the practice of Ylva Ogland represents one of the most interesting attempts to build a bridge between autobiographical details and fictional fable-like elements in order to create what could be defined as “personal mythologies.” In doing so the artist explores all the facets of painting, which alphabet and grammar she has been mastering since the very early stage of her life. The result – which could be called “expanded painting” – not only encompasses traditional oil on canvas but also installations, performances and large-scale environments. Albeit contemporary and absolutely informed about its surroundings, the work of Ylva Ogland – its dark melancholia and esoteric spiritualism – represents an indisputable example of a Nordic sensibility that links her practice to figures such as Edvard Munch and Hilma af Klint but at the same time it bears traces of artists as diverse as Marcel Duchamp and Tracey Emin. The Loka series (2003-06) represents a turning point within her practice. The daughter of an artist, Ogland studied painting already when she was a child and then she was accepted at the Royal Academy of Fine Art at the age of 19 and successively had a recidency at Iaspis when she was very young. During these formative years, influenced by the dynamic scene in Stockholm and by feminist thinkers, the artist decided to abandon painting – from which she felt saturation and repulsion – and started to work as a curator and specifically as one of the directors of Tensta Konsthall. Painted during this less active period, Loka nr1, which belongs to the series with the same title, became one of the keys for her return to painting and also one of the earliest examples of what is widely known as her signature works, which consist of figurative paintings mixing details from her childhood, personal legends and elements from the history of art rendered with a unique technique which includes the use of a very strict palette spamming from grey to pink. In fact after this series the artist begun to be again active in the art field as a practicing artist, a choice, which went hand-in-hand with the conclusion of her curatorial experience. However it is important to understand that this more conceptual and intellectual side of her practice was never fully put aside because all her artworks have, since her return to painting, been deeply influenced by the notion of display and exhibition making. The title of the painting and related series comes from the name of an old manor in the north of Sweden where the father of the artist lived – whose portraits in different phases of his turbulent life are a recurring subject within her practice. Although the scene seems to depict a detail of the garden outside the house, with the little roof and the bench covered by snow, when inspected more in detail the scene reveals to be the super-imposition between the outside of the manor and its inside, which is represented by two objects hanged on what would be otherwise an empty wall. On a closer look we realize that these two objects are in fact the reproduction of two paintings, which give a meta-linguistic value to the work and confirm Ogland’s deep interest in the language of painting since the very beginning of her path as a mature artist. The two ‘paintings’ in the painting are respectively reproductions, assembled in dada style, one of them being a circular object featuring a detail of Leonardo Da Vinci’s masterpiece La Gioconda, which we can see from a hole on this tondo-like object. Here again the artist uses her skilled technique to reflect on the very history of the medium. These trompe-l’oeil ‘paintings-of-paintings’ are also a manifesto of what still dominates Ogland’s practice: on one hand the personal, embodied by the images belonging to the world of her father, which she diligently copied; on the other hand the history of art here symbolized by La Gioconda. The most interesting side of this analysis is the fact that what at first sight appears as a dichotomy, is in fact an intercourse. In other words the personal is here presented through a work of art, an installation at her father's home, while the art historical is brought in the picture through an artwork, which has been the subject of many speculation regarding the life of his author, Leonardo. By creating this intricate web of references, Ogland invites us to ‘enter the painting’ and discover a parallel reality in which all certitudes must be reconsidered through the eyes of the artist as Demiurge.

Nicola Trezzi

US Editor, Flash Art International

Curator, Prague Biennale Foundation

Critic in painting/printmaking, Yale University School of Art