Kjell Anderson

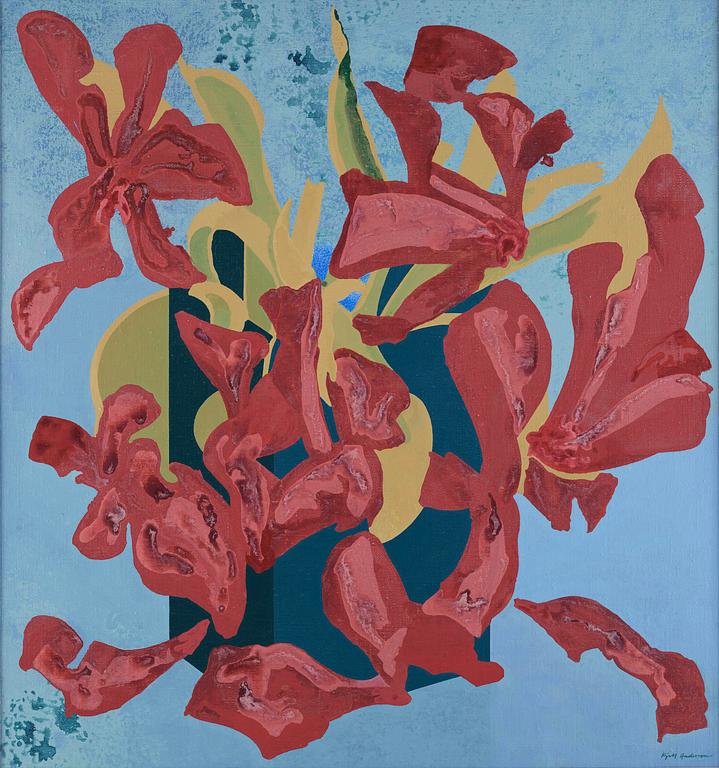

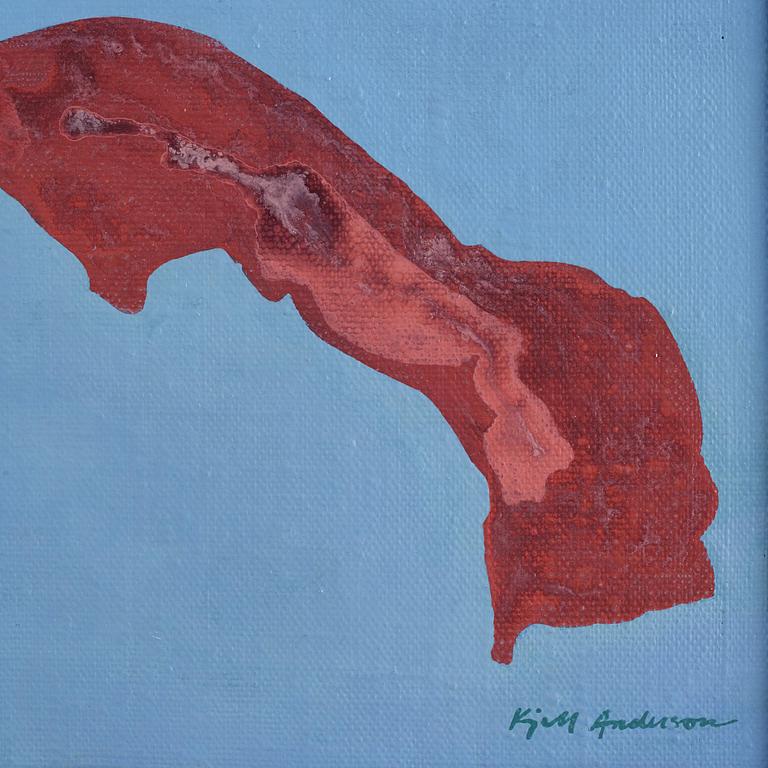

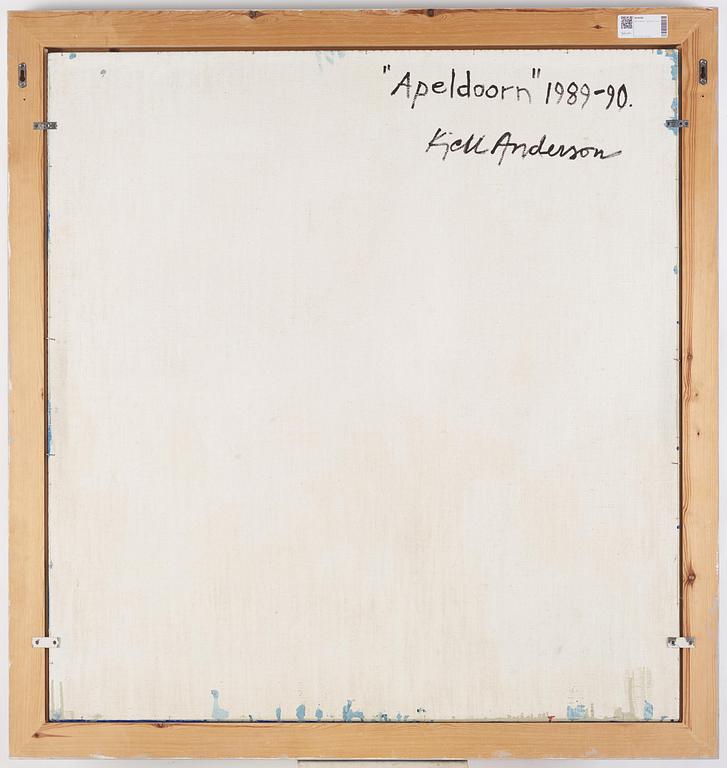

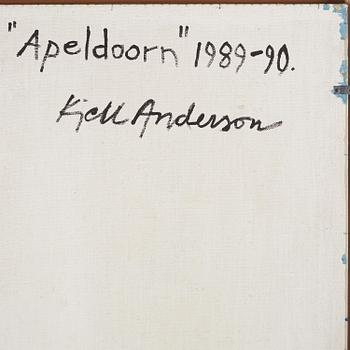

Kjell Anderson, "Apeldoorn"

Signed Kjell Anderson and dated 1989-90 on the reverse. Canvas 119 x 111 cm.

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Sivert Oldenvi Collection

Näyttelyt

Prince Eugen's Waldemarsudde, Stockholm, "Thirteen Contemporary, 26 December 1990 - 10 March 1991."

Kirjallisuus

Prince Eugen's Waldemarsudde, Stockholm, Exhibition Catalogue, "Thirteen Contemporary", p. 33.

Muut tiedot

Kjell Anderson, born in 1937, worked as a decorator and stagehand in Stockholm for many years. With a background as a trumpeter in the orchestra "Lobsters" in Karlskoga, he spent his free evenings at the jazz club Nalen. Studies at Anders Beckman's school led to a position at an advertising agency and a budding interest in art. The Moderna Museet exhibition "4 Americans" in 1962 had a strong impact on him. Oil paints were purchased, and he completed a painting that was subsequently accepted at Vårsalongen at Liljevalchs konsthall. Anderson applied to the Royal Institute of Art but was not admitted. He continued to apply each year until he was finally accepted in 1967. The disappointment of not being admitted directly to the Royal Institute of Art led him to later perceive being an artist as a privilege.

His first exhibition took place at Galerie Burén, and a few of years later, Anderson exhibited together with his co-founders and friends Bo Larsson and Kjell Strandqvist at Konstnärsbolaget. In the 1980s, Konstnärsbolaget was dissolved, and Anderson got a new studio in the Münchenbryggeriet in Stockholm and became associated with Galleri Olsson, with recurring solo exhibitions from 1982 to 2011.

The ideals of modernism and the contradictions between painting and installation were hotly debated throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The art market was characterised by oversaturation as the supply had developed explosively. Among those who stubbornly continued to challenge and develop the logic of modernism were Kjell Anderson, the friends who had founded Konstnärsbolaget, and its successors.

Mårten Castenfors writes in the essay ‘In the Wake of Modernism’ (SAK publication 110):

“Even Kjell Anderson applied his colour in a restrained and balanced manner during the 1990s, but unlike Strandqvist, there were small retained references to nature and objects in the works. It grew like flowers on the surface, but the flourishing was merely a pretext to explore the possibilities of painting, where colour and form created their own nature. In Anderson's controlled dryness yet simultaneously subtle colouration, there was a shadow of the elder Lennart Rodhes' formal demands, with a pictorial logic where the thematic and formal improvisation could not take too many extravagant leaps.”