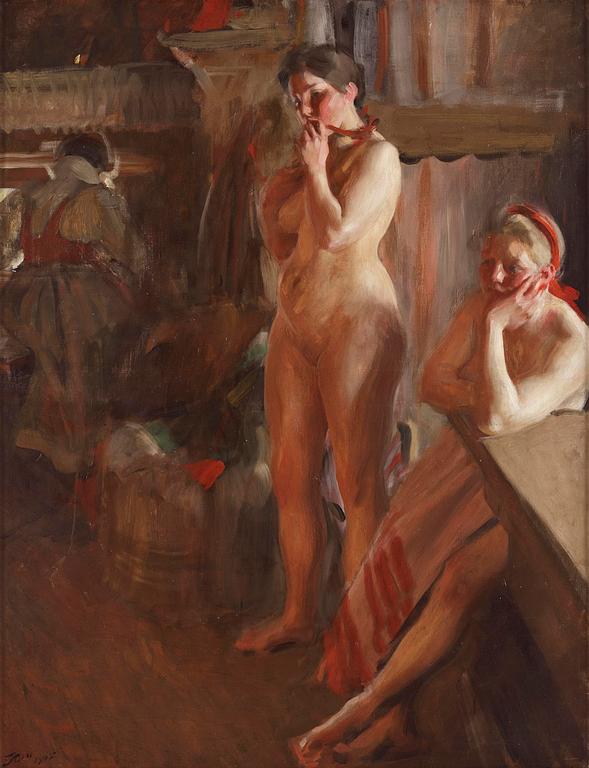

Anders Zorn

"Eldsken"

Signed Zorn and dated 1905. Oil on canvas 107 x 82 cm.

Tuontiarvonlisävero

Tuontiarvonlisävero (12%) tullaan veloittamaan tämän esineen vasarahinnasta. Lisätietoja saat soittamalla Ruotsin asiakaspalvelumme numeroon +46 8-614 08 00.

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Mr. Woodruff J. Parker (1890 - 1930), corporate lawyer, art collector and governing member of The Art Institute of Chicago.

The Art Institute of Chicago, gifted from the above 1926.

Sothebys, New York, 19th Century European Paintings and Sculpture, 23 May 1990, lot 46.

Bukowski Auktioner, Internationella Höstauktionen 526, 26–28 November 1997, lot 183.

Sothebys, London, 19th Century European Paintings, 3 jJune 2003, lot 243.

Näyttelyt

Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm, ”Invigningsutställning: Larsson-Liljefors-Zorn”, March - April 1916, kat. no 54.

Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, "Svenska Konstutställningen", November - December 1916,

cat. no 806.

The Art Institute of Chicago, "A century of progress exhibition of paintings and sculpture", 1 June - 1 November 1933, cat. no 276 (from the collection of The Art Institute of Chicago).

Kirjallisuus

Ernst Malmberg, ”Larsson-Liljefors-Zorn. En återblick”, 1919, mentioned p. 112 and illustrated.

Tor Hedberg, ”Anders Zorn 1894–1920”, SAK, 1924, mentioned p. 90.

Albert Engström, ”Anders Zorn”, 1932, illustrated full page p. 119.

Gerda Boëthius, "ZORN -Tecknaren, Målaren, Etsaren, Skulptören", 1949, mentioned p. 454 listed in the register under the year 1905, p. 551.

Gerda Boëthius, ”Zorn -Människan och konstnären”, 1960, illustrated full page fig.48.

Muut tiedot

After the turn of the century 1900, Anders Zorn came to be recognised as an ardent advocate of local culture, with the aim of making Dalecarlian culture a national concern. Zorn's dedication to his homeland often found expression in property acquisitions and extensions to existing buildings. The studio in Mora, originally an old firehouse relocated from Fåsås, was soon complemented by another timber building, the so-called Risaloftet, which was constructed adjacent to the studio near the main entrance to Zorngården.

“Eldsken” (Firelight) was painted in the autumn of 1905 and is an intricate composition in which Anders Zorn allows the firelight to illuminate the interior scene. The painting was created in Gopsmorstugan, a dual-purpose structure serving as both a wilderness studio and fishing cabin that Zorn had built on the Dalälven river ‘opposite Gopsberget and the mouth of the Gopelån river, where the mountain reflected all its majesty in the water’. Zorn acquired a fully preserved cottage from 1766, ‘one of the only ones left with a ridge roof in Mora’, purchased the land in question, and had the cottage reassembled with the help of his uncles Lars and Per. The location could not have been better chosen, according to Zorn: ‘soaring pines and spruces and at its foot a lovely spring stream, then on the other side of the cottage the flowing Dalälven and beyond this the stately Gopsberget. It was ideal, and I began the following summer to stay there as soon as the cottage was finished.’ Zorn often referred to ‘Gopsmorsstugan, this so peaceful and for my health so important corner among tall spruce trees and with the Dalälven rippling outside on the way to the sea.’ He frequently welcomed visitors there; the academy member Karlfeldt spent the night in the cottage, and Bruno Liljefors travelled there to have his portrait painted in the winter-white spruce forest.

Life in Gopsmor was simple and rustic, with a diet consisting mainly of herring, potatoes, and gruel. Although some of Zorn's guests in Gopsmor found the conditions a little too spartan, the beneficial impact of his stays there on Zorn's creativity and inspiration is unmistakable. Zorn worked diligently in Gopsmor, particularly in winter when the limited hours of daylight were never enough. It seemed as though an extra zeal and joy of work overtook him as soon as he managed to reach the remote studio. Several of the artist's most famous paintings were created there, including Dans i Gopsmorstugan (Dancing in Gopsmorstugan, 1914), one of his most beloved motifs.

Zorn was particularly fascinated by the unique lighting conditions in the log cabin. The sparsely lit interior placed high demands on the artist's ability to make the most of the available light, with many of his compositions created solely in the glow of the open hearth.

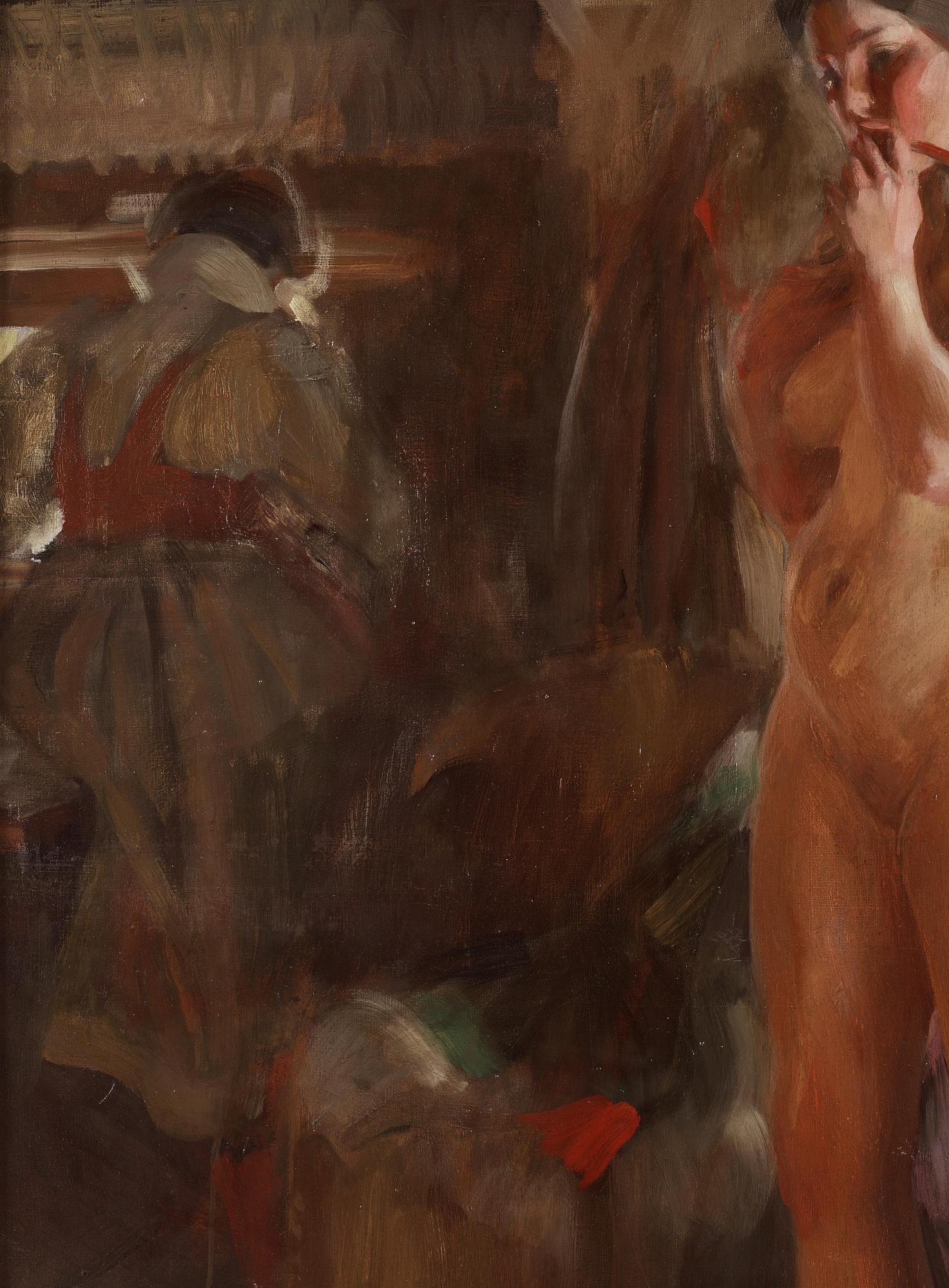

In Eldsken (Firelight), Zorn skilfully captures the reflections of the firelight on the cottage’s walls and the bodies of the Dalecarlian women. The village’s peasant culture is reflected in the two Mora costumes—one worn by the Dalecarlian woman in the background, and the other taken off by one of the naked Dalecarlian women and placed on the floor. Zorn demonstrates his mastery as a colourist by emphasising the vibrant and intense hues of the Mora costumes, using them as striking accents within the composition. Hans Henrik Brummer refers to these works in one of his books as ‘faithful tributes to the colourfulness of the Mora costume.’

The Mora costumes in particular were part of Zorn's ambition to preserve Dalecarlian culture and shield it from the rapid transformations of industrialisation. In his paintings from Mora and its surroundings, Zorn often conveyed a deep respect for tradition, for example by highlighting the cultural uniqueness of the costumes. In doing so, he paid tribute to the people of Dalecarlian culture for holding on to their history. Zorn´s mother, Grudd Anna Andersdotter, represented his homeland in a very personal way. In 1874, his mother married Skeri Anders Andersson, with whom she had four daughters. The family’s life was often challenging, marked by overcrowding and poverty. When Zorn’s career took off in England during the 1880s, he sought to alleviate his mother’s situation by sending financial support. After acquiring part of the Skeri farm near Mora church in 1886, Zorn began to use members of the Grudd and Skeri families as models for his paintings, for example in Vårt dagliga bröd (Our Daily Bread, Nationalmuseum). The models were dressed in old-fashioned clothing to recreate the costumes of his childhood. Zorn remained committed throughout his life to preserving the national costume, and his depictions of Dalecarlian women and craftsmen reflect his determination to document their distinctive attire with realism and respect for future generations.

Picture 1. Anders Zorn in Mora costume at Risaloftet, Zorngården 1905. Photo: H. Wikander, Mora.

Picture 2. Exhibition picture The Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Picture 3. Gopsmorsstugan with the stream and Gopsberget. Photographer: Anders Flodin, spring 1957. Zorngården.