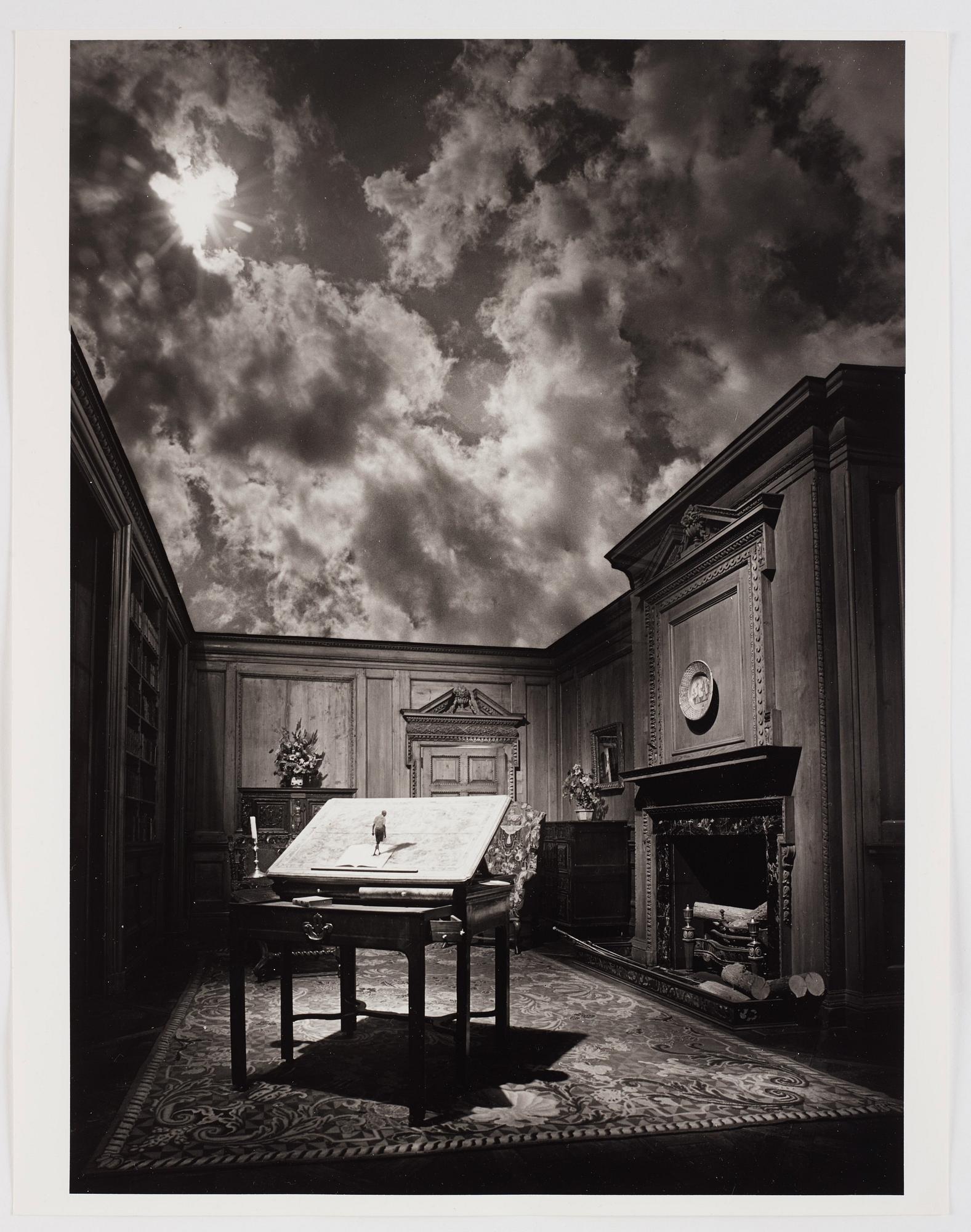

Jerry N. Uelsmann

'Philosopher's Desk', 1976

Signed Jerry N. Uelsmann and copyright stamp verso. Gelatin silver print, image 31.8 x 26.5 cm. Sheet 35.5 x 27.7 cm.

Kirjallisuus

Jerry Uelsmann and A.D. Coleman, 'Jerry Uelsmann: Photo Synthesis', 1985, illustrated on cover.

Muut tiedot

Quote from Richard Sandomir's article in New York Times on April 13 2022:

"Jerry Uelsmann, a photographer who ingeniously used darkroom techniques to manipulate his black-and-white pictures into surreal montages that anticipated by many years the digital image-editing revolutionized by Adobe Photoshop, died on April 4 in Gainesville, Fla. He was 87.

The cause was complications of a stroke, his son, Andrew, said.

Mr. Uelsmann’s dreamlike imagery seems to ignore the laws of gravity and rationality, much as the paintings of Rene Magritte did.

In Mr. Uelsmann’s imaginative alternate universe, boats float above clouds and waterfalls. Hands that morph from a tree trunk gently hold a bird’s nest. Five empty chairs situated magically on a pond face a fifth chair, as if they’re holding a meeting. A young nude woman whose lower body is only a foggy mist hovers over mountains.

“The primary creative gesture for most photographers used to be when they clicked the shutter,” Mr. Uelsmann (pronounced YULES-man) told Smithsonian magazine in 2013. “But I realized that the darkroom was a visual research lab where the creative process could continue.”

To choose the images that he would combine, he combed through stacks of his contact sheets from years past.

“I start seeing how images might fit together,” he said in an interview in 2011 with the Lens blog of The New York Times. “There’s a kind of cognition. I’ll be working on an image, and I’ll remember a photograph I made 20 years earlier or 15 years earlier. I have to find the negative that I think might fit into that context.”

Working in his darkroom with as many as seven enlargers, each holding a different negative, Mr. Uelsmann moved a sheet of photographic paper from enlarger to enlarger. He printed a different element from each negative, creating a photomontage that could be filled with paradoxes, wonder and symbolism. Sometimes it took days to make a print that satisfied him.

“If I have an ultimate goal,” Mr. Uelsmann told The Times, “it is to amaze myself.”

Philip Gefter, a photography critic, wrote in an email that Mr. Uelsmann “artfully juxtaposed his very precise photographs of actual objects, creating unusual incongruities to surreal effects.”

“His intensions were wholly symbolic and based on psychological archetypes of a Jungian nature,” Mr. Gefter added.

Mr. Uelsmann’s work has been widely exhibited in the United States and Europe. In New York it was included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2012 show “Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop,” which traveled to other cities. One of his montages in the show was that of a tiny Victorian study with its ceiling open to the sky and, on a desk, a tiny man walking on a map. (Mr. Uelsmann had photographed the man walking on a beach.)

Mia Fineman, who curated the show, said of Mr. Uelsmann in a telephone interview: “He was outside of the mainstream of photographic art-making, which really had a fixation on the purity of the straight photograph and the idea of previsualization — that step where the photographer should be able to visualize the finished print at the moment you click the shutter. He went against all that.”

Jerry Norman Uelsmann was born on June 11, 1934, in Detroit. His father, Norman, owned a grocery store, where Jerry worked as a delivery boy. His mother, Florence (Crossman) Uelsmann, was a homemaker. At 12, Jerry began taking drawing lessons at the Detroit Institute of Arts Museum, where he became fascinated by Van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait.”

In high school he was a photographer for the student newspaper and worked at a photography studio.

When he entered the Rochester Institute of Technology in upstate New York, his goal was to be a portrait photographer. But under the influence of teachers like the photographer Minor White (who called the camera a “metamorphosing machine,” Mr. Uelsmann said), he began to see a wider world in photography.

After graduating with a bachelor of fine arts degree in 1957, Mr. Uelsmann earned a master’s in audio visual communications and a master of fine arts in photography at Indiana University in 1960.

From 1960 to 1998, he taught photography at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Early on, in a group darkroom there, he first made use of multiple enlargers, an innovative approach that accelerated his creation of photomontages. He received a Guggenheim fellowship in photography in 1967, the year he had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

John Szarkowski, the renowned director of MoMA’s department of photography, once said in an interview with The Daily News of New York that Mr. Uelsmann dared to question the finality of a picture once it had been taken.

“He meditates on his pictures, experiments with print techniques, recombining pictures,” Mr. Szarkowski said, “and the result is truly artistic and new.”

Mr. Uelsmann’s books and monographs include “Uelsmann: Process and Perception” (1985); “Silver Meditations” (1988) and “Uelsmann Untitled: A Retrospective” (2014, with Carol McCusker).

Describing Mr. Uelsmann’s home studio in Gainesville in “Uelsmann Untitled,” Ms. McCusker wrote that his walls were “pinned with cartoons, dolls’ heads, strange toys that move or talk, 3-D sculptures of Hieronymus Bosch and 19th-century Victoriana,” and that his shelves were filled with camera memorabilia, mug shots and gizmos — all of which seemed to form a chorus “that silently encourages or inspires his next creation.”

In addition to his son, Mr. Uelsmann, who died in a hospice facility, is survived by two grandchildren. His marriages to Marilyn Schlott, Diane Faris and Maggie Taylor ended in divorce.

Mr. Uelsmann understood the benefits of using Photoshop, which was developed by Adobe in the late 1980s, but he chose not to abandon his analog artistry. He used a computer, but only for email.

“If I were 22, I would probably be working in Photoshop,” he told The Times.

And Photoshop appeared to appreciate him. In 2013, its Twitter account shared an article about Mr. Uelsmann’s photographic manipulation with a message that said, “Jerry Uelsmann’s incredible composites remind us that imagination is everything.”

His former wife Ms. Taylor, a digital artist who uses Photoshop, recalled that Adobe approached Mr. Uelsmann in the mid-1980s to create a poster image to promote a new version of Photoshop.

It was his introduction to the software. Adobe scanned some of his negatives and sent an expert to help him create a final photomontage of clouds resting in the palms of two hands while a rowboat floats unattended in the water nearby. He decided which elements to put where, but did not know how to use the software.

“He liked the image and decided to take the negatives into the darkroom and recreate it photographically,” Ms. Taylor wrote in an email. “Working in the wet darkroom was an integral part of his creative process; sitting at a desk was not for him.”