The "De Geer cabinets" a pair of demi-lune cabinets by Georg Haupt (master in Stockholm 1770-1784), Gustavian.

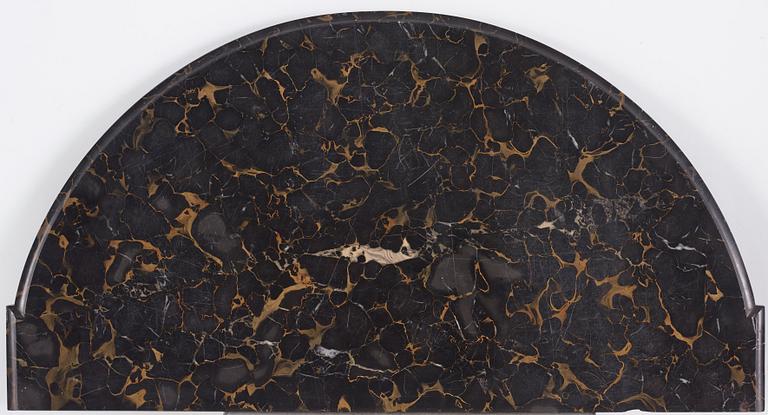

Each with a Portor marble top with a moulded edge above a frieze drawer inlaid with fluted fields framed in optical relief, above a cabinet dorr inlaid with medallion profile heads within a laurel frame, flanked on each side by latticework and rosette fields, within a further frame composed of latticework and ribbons, enclosing a shelf interior, on three cabriole legs with acanthus-swag mounts. Length 66, width 33, height 88, and 89 cm respectively. 3 keys included.

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Baroness Catharina Charlotta Ribbing af Zernava (1720-1787), widow of Baron Charles De Geer af Leufsta (1720-1778) inherited by her son

Baron Louis De Geer af Leufsta (1759-1830), inherited by his daughter

Lovisa Fredrika, married to Count Gustaf Wachtmeister af Johannishus (1796-1882), inherited by their son

Count Carl Fredrik Wachtmeister af Johannishus (1830-1889),

Thence by decent

Kirjallisuus

Svenska slott och herresäten: Södermanland, Stockholm 1908, Christineholm,, page 272, depicted pages 271 and 272.

Slott och Herresäten i Sverige: Södermanland 1, Malmö 1968, Christineholm, page 70.

Ljungström, Lars: Georg Haupt, Gustav III: hovschatullmakare, Kungl. Husgerådskammaren, kat.nr 36, Stockholm 2006, page 57, depicted on pages 56 and 81.

Muut tiedot

The De Geer Cabinets, unparalleled carpentry technique and design

The two cabinets in the auction embody everything associated with Georg Haupt: refined design and decoration, innovative style, and his legendary craftsmanship. In Haupt's well-known production, these cabinets hold a special position with their unique design and technically advanced execution. Haupt introduces a type of furniture that had not previously existed in Sweden. Furniture with a semi-circular facade can be found in both France and England, and as Lars Ljungström has shown, Haupt drew inspiration from England, where the emphasis is on volume and the facades have doors. However, the cabinets in the auction are narrower, resulting in a semi-circular door. Constructing a 180-degree curved surface and decorating it with rich intarsia decoration demonstrates a technical skill possessed by no other Swedish cabinetmaker during the 18th century.

As on several of Haupt's most exclusive furniture pieces, he has for the tops chosen precious imported marble, in this case, black and yellow speckled marble, known as portor. Portor surfaces can be found, for example, on the pair of encoignures, corner cabinets, and bookcases by Haupt from around 1780, which were previously located in Gustav III's Divan Room at the Royal Palace in Stockholm. On the pair of corner cabinets, it can be seen that the precious and custom-made surfaces likely arrived when the cabinets were almost finished. The surfaces are elegantly thin at the front edge, but then become thicker and roughly hewn underneath, a thickness that Haupt had not anticipated. Afterwards, he had to use a chisel to make substantial hollows in the upper blind panels of the corner cabinets to accommodate the thick surfaces.

On one of the cabinets in the auction, the one with the male medallion, we find the same phenomenon, indicating that it had been completed when the marble tops arrived. To avoid this on the other cabinet, Haupt raised the facade slightly to accommodate the thickness, resulting in a one-centimeter increase in height.

To truly showcase his masterful craftsmanship, Georg Haupt has not only settled for a semi-circular surface on the cabinets in the auction. He decorates it with unusually abundant intarsia in the form of lattice patterns with small rosettes, grillwork, and a classical portrait medallion, cannelures, framework, and ribbon rosettes. Additionally, we find his refined shading to create a sense of depth. Haupt himself described the decoration in an invoice for a table in 1777 for Princess Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta as "inlaid medallion and antique head, along with mosaic." We recognize the motif from some of Haupt's most famous furniture pieces, such as the so-called Österbybruk Secretary from 1779 (private collection) and the pair of secretaries commissioned by Prince Fredrik Adolf in 1778, now at Tullgarn Palace. As Lars Ljungström writes in his catalog from the Haupt Exhibition at the Royal Palace, Stockholm, in 2006, these cabinets are exceptionally well-preserved. The untouched surfaces offer an opportunity today to appreciate Haupt's way of composing intarsia and how he brought it to life with his unparalleled engraving skill.

Catharina Charlotta Ribbing and the De Geer Palace

The recipient and orderer of these elegant cabinets was the famous Baroness De Geer, Catharina Charlotta Ribbing af Zernava (1720-1787). She belonged to the influential elite of her time and had a strong personality. It caused a great stir when she became the first in "high society" to inoculate her children against smallpox, resulting in Carl Gustaf Tessin having a medal struck in her honor in 1756. At the age of only 23, she married one of the wealthiest magnates of the time, Baron Charles De Geer af Leufsta (1720-1778). This allowed her to freely pursue her interests in architecture, art, and interior design, which can still be seen at Leufsta, Stora Wäsby, and Svindersvik. Baron Charles De Geer had purchased the plot on the corner of Västra Trädgårdsgatan and Kocksgränd. There, he began building a house that could serve as a future widow's residence, although it was not completed at the time of his death in 1778. It was up to his widow to finish the house (now the residence of the Finnish ambassador), and she had the assistance of Jean Eric Rehn. In his own handwritten catalog, Rehn writes: "built from the ground up the current house of the Baroness De Geer on Västra Trädgårdsgatan, as well as the entire interior of the same house." As a widow, Catharina Charlotta De Geer remained very wealthy and maintained a grand house in Stockholm and was part of Gustaf III's personal circle, where she had the opportunity to see the works delivered by Georg Haupt.

At Charles' death in 1778, the auction's cabinets are not listed in the estate inventory, so we can assume that it was Catharina Charlotta who ordered them in the latest style from Haupt. She moved into the house in 1784, the same year Haupt died, which allows us to confidently date the cabinets between 1778-1784. This also aligns stylistically, as we have seen, with other furniture Haupt produced during this time for the king and others. Just three years later, Catharina Charlotta dies, and through her estate inventory in 1787, we can get an idea of the rich interior of the De Geer Palace. Her grand bedroom was, as usual, also uset as room for entertaining. The decor was in white and gold with rich red textiles and furnished with no less than 13 seating furniture, two gilded console tables, and 7 pieces of veneered furniture. Among the latter, the auction's cabinets are listed: "2 Half-round small bureaus with brown marble tops, various types of inlaid wood, and gilded mounts." It is interesting to note the mixture of colors of the tops, with white, gray, and brown marble tops being used in the same room.

The exact placement of the cabinets in the room is not specified, but on a preserved floor plan, narrow pilasters are drawn on either side of a fireplace, which is not found in other rooms. These pilasters have the same width as the auction's cabinets, indicating that that the cabinets most probably were placed against them, flanking the tiled stove.

The house and the majority of the interior were inherited in 1787 by the youngest son, Louis De Geer (1759-1830), and from the estate inventories of his two wives (1794 and 1815), it is evident that the cabinets remained in the bedroom. In 1818, he sold the palace and moved the cabinets to Nyköping and Christineholm. In the estate inventory of his grandson Carl Fredrik Wachtmeister in 1889, the cabinets are placed in the salon there, where they have remained until recently.

With their unbroken provenance, unique design, and untouched condition, the auction's cabinets offer an opportunity to acquire a unique memento of Swedish 18th century.