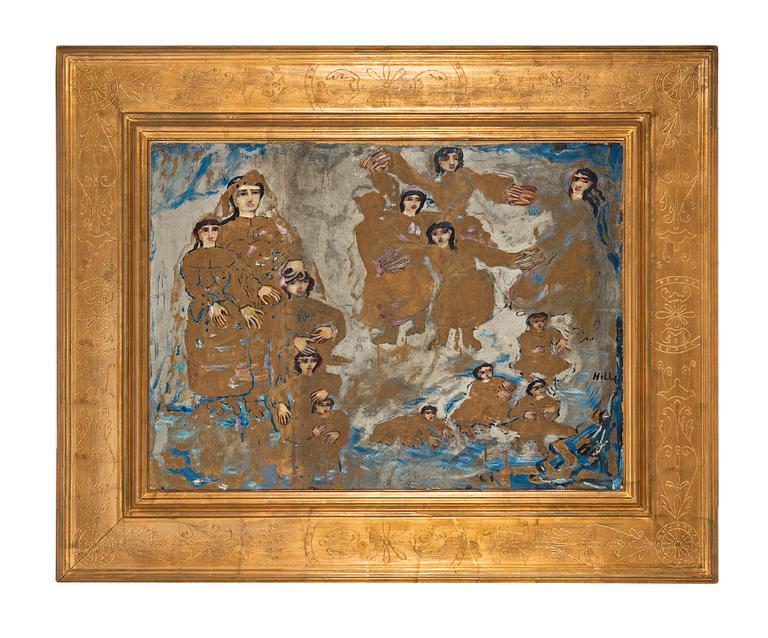

Carl Fredrik Hill

'Familjen - variation I' (The Family - variation I)

Signed Hill. Silver, gold bronze and oil over traced pencil on paper-panel mounted on canvas 55 x 75 cm.

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Originally in the artist's deceased estate; Subsequently by descent within the family; Private Collection; Nordén auktioner, Stockholm, auction 25, 'Vårauktionen', 23 April 1997, cat. no 170; Private Collection; Bukowski Auktioner AB, auction 571, "Höstens Klassiska Auktion", December 4 - 7, 2012, cat. no 41; Private Collection.

Näyttelyt

Malmö Konsthall, Sweden, 'Carl Fredrik Hill', April 10 - June 7,1976, cat. no 67; Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden, 'Carl Fredrik Hill', October 1, 1999 - January 16, 2000, cat. no 105, Blaafarvevaerket, Åmot, Norway, 'Kong Jeg', May 18 - September 22, 2002, cat. no 69.

Kirjallisuus

Nils Lindhagen, 'Carl Fredrik Hill. Sjukdomsårens konst', 1976, illustrated half page in the catalogue section, no. 271.

Sten Åke Nilsson, 'Bildflödet. Om sjukdomstidens teckningar', article in "Carl Fredrik Hill", exhibition catalogue, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden, 1999, illustrated half page in colour, p. 152.

Muut tiedot

Towards the end of 1877 and after an extended period of stress, Carl Fredrik Hill’s mental health collapsed. In the first days of 1878, his concerned neighbours called for Hill’s friend Willhelm von Gegerfelt to come. Gegerfelt, who quickly realised the seriousness of the situation, took care of Hill as best as he could. It was also Gegerfelt who, on the 18th of January 1878, arranged for Hill’s transportation to Doctor Blanche’s clinic in Passy, outside of Paris, where he was sectioned against his will. This sectioning can generally be seen as a watershed moment in Hill’s artistic production. He was a traditional landscape painter but withdrew for a time only to return as a visionary interpreter of highly personal inner landscapes.

Hill’s later production of drawings has often been called his ‘period of illness’. In the 1999 catalogue for the National Museum’s major exhibition Carl Fredrik Hill, one of Sweden’s foremost experts on Hill and his art, Sten Åke Nilsson, gave the following insight into this later work: “After he was sectioned it is possible to discern a certain decline in Hill’s production. […] But the notes from the hospital in Lund already attest to a new and different flow of images, and the return to Skomakargatan appears to set unexpected powers free. The contact with his own early work, with texts and image material from his father’s library, has a stimulating effect. […] After the long break he works again, at times with the same intensity as before his sectioning”.

In all likelihood the return to his well-ordered, bourgeois childhood home seems to have had a calming influence on Hill. His mother and his beloved sisters were also there. Even if family life constituted a sanctuary for the artist’s tormented soul, this did not mean that Hill’s flow of inspiration was in any way interrupted. As the head of the family, irrespective of his health, Hill still had the use of the library that his deceased father had left behind, which, together with the rest of the family’s collection of books, was all the inspiration he needed. Although the family had sold off some non-fiction books after his father’s passing, several volumes still remained in the home on Skomakargatan. It was above all the xylographic illustrations that aroused Hill’s interest. The family’s trips to Copenhagen and its museums are also said to have stimulated Hill’s imagination. Besides straightforward repetitions of his own earlier landscape motifs, in the following years, Hill focused his attention on sourcing material as diverse as antique sculptures, 17th-century painting, and images reporting from ‘deepest’ Africa. We also know that Hill would often return to a particular volume, that of Ernst Wallis’s Illustrated World History.

Sten Åke Nilsson additionally connects Carl Fredrik Hills production from this period with the artist’s preserved painting case (Kulturen i Lund): “Carl Fredrik Hill’s painting case has been preserved. Amongst other things it contains a palette, twenty-three rather squeezed out tubes of oil paint, a dirty brush, a couple of charcoal pencils and a pencil marked ‘J.W. Guttknecht No. 2’. This material could surely not have come back with him from Paris. Not a single one of the paint tubes in the box is of French origin, they are from Düsseldorf or Berlin. It all points to them being acquired in Lund or Copenhagen in order to give Hill another chance as a painter. In Versmanuskriptet he complains about his hopeless situation: ‘The grief that erodes the artist when the brush is coerced by necessity, rest distich lament, the artist snared, asking in vain for his brush’. The family finally gave in to his prayers, but the experiment is short-lived. In a letter from 1888, his mother writes how there is no use spending money on oil paints, and Hill admits in Versmanuskriptet that he finds it difficult to handle his material: ‘Alas I break the brush at my easel…’ There are also plenty of stains of gilded bronze and silver tincture in the box and on the palette, traces of Hill’s work on a number of gold paintings. Most of these have been executed as drawings on cartridge or wrapping paper, traced and painted over. Others, like the oils, have been painted on cardboard in slightly larger formats. Judging by the traces of colour Hill transitioned from oil to gilded bronze and silver”.

From this information we should be able to conclude that Familjen – variation I probably belong to the paintings that were executed in either 1886 or 1887. Even if this cannot be fully substantiated there is much that speaks for the composition at least having been made during the end of the 1800s.

The subject of the painting shares strikingly clear points of contact with a limited number of similar compositions in gold and silver. The biggest similarity can be found with Figurer på guldgrund (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm), the measurements, format and composition of which are noticeably comparable.

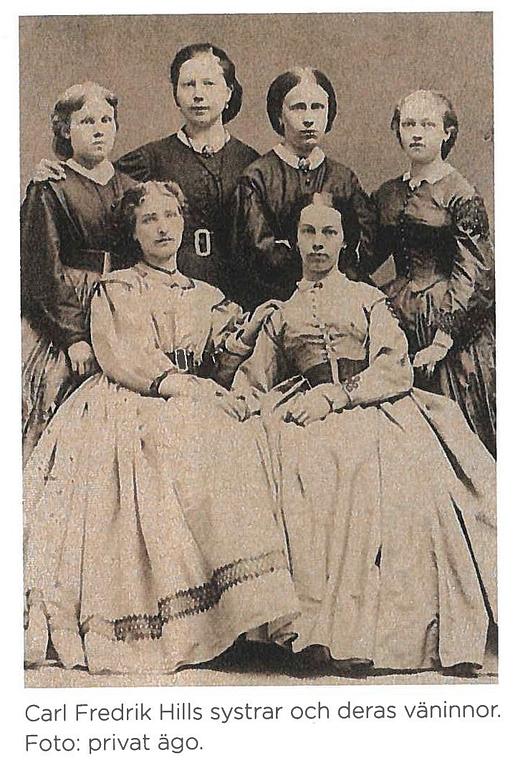

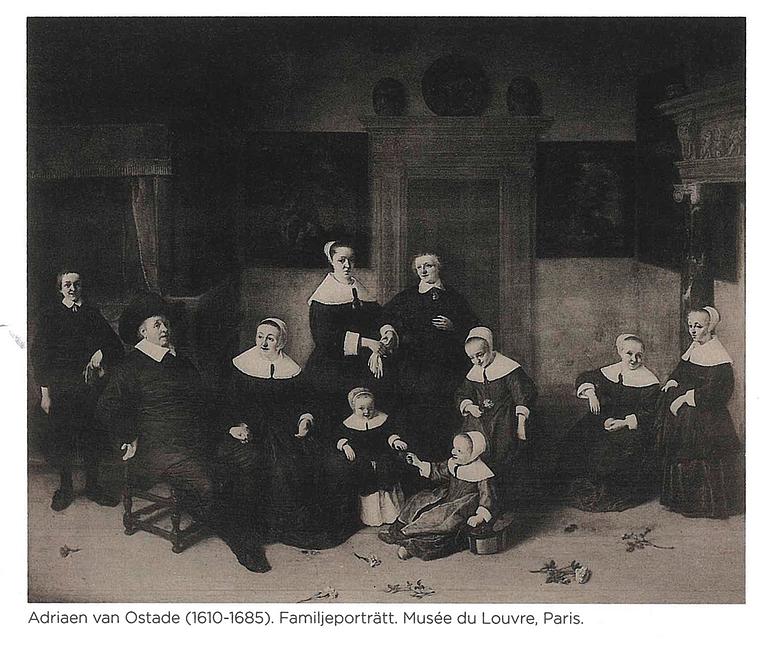

Once more Sten Åke Nilsson deepens our knowledge about these unusual subjects in gold and silver, as he writes: “Hill’s drawings and compositions in gold and silver contain several figures with the twins’ thick limbs and wide feet. They are not staring down into any imaginary depths but seem instead on their way towards a higher realm. They are captured in a conjoined, ascending movement. Flames are shooting up from below, the silver foundation enveloping them. It appears to be about torment and liberation, about the transition to a different existence. Other drawings and gold paintings depict the female world that Hill belonged in during his many years living in the house on Skomakargatan. […] In a pencil drawing we see the mother, the sisters and the grandchildren all gathered. The atmosphere is formal as grace is being said. The image has a dedication to ‘Hedda Hill’, and could have, as Nils Lindhagen has suggested, been executed ahead of Hill’s sister’s 50th birthday in 1895. […] The ideals that Hill had in mind when he made his drawings are taken from bourgeois interiors such as Adriaen van Ostade’s Portrait of a Family, now in the Louvre. Like in the Hills’ household it is the women and children that dominate the scene, their large collars and cuffs shining brightly in white. The gazes seem fixed, whilst the hands perform their own ballet across the pleated layers of fabric. To assist him, Hill also had photographs taken of his sisters and their friends placed in formal groupings and in similar clothes. The gold paintings are variations on the same theme. They are considerably bigger, and the pictorial space is filled with more women braiding each other’s hair and taking each other’s hands. Some are joined in a ring game. In several instances, we are able to make out interior details around the figures, such as tall doors, tiled stoves and pier mirrors. But streaks of colour and sheets of gold and silver guide us towards the abstract – and we end up somewhere in between shimmering Byzantine mosaics and Gustav Klimt’s ornamental compositions. The bourgeois interior is not just shattered in its form, but the room is opened towards the unexpected. […] The technique must have held a special lure. Hill had long been fascinated by gold as a phenomenon. On his images of Normandie beaches, he wrote ‘de l’or’ and ‘lumière dorée’ and in his paintings from the autumn of 1877 he worked with skies almost like the gold ground employed by primitive masters. Yet it was not until the sanctity of his workshop in Lund that he allowed himself to let gilded bronze and silver tincture to run across his drawings”.