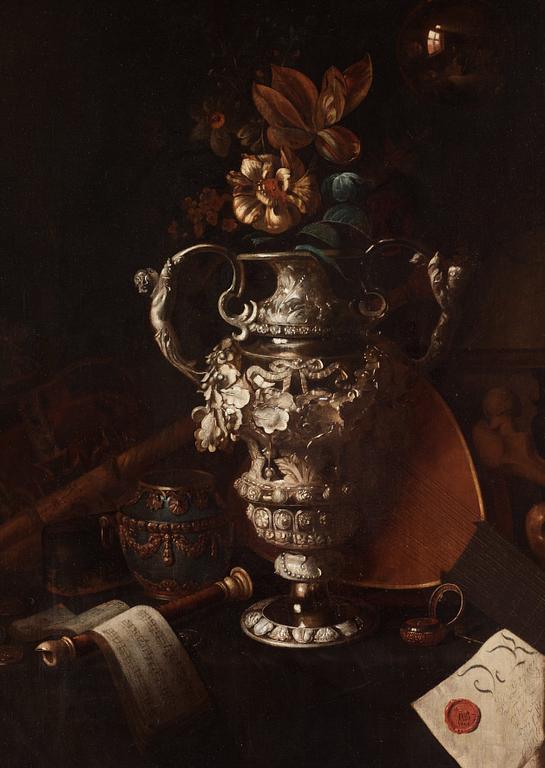

Pieter Gerritsz. van Roestraten

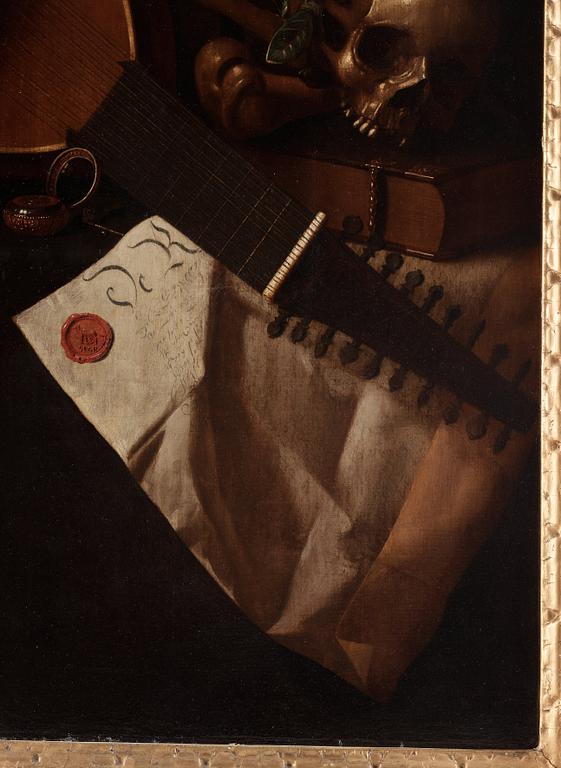

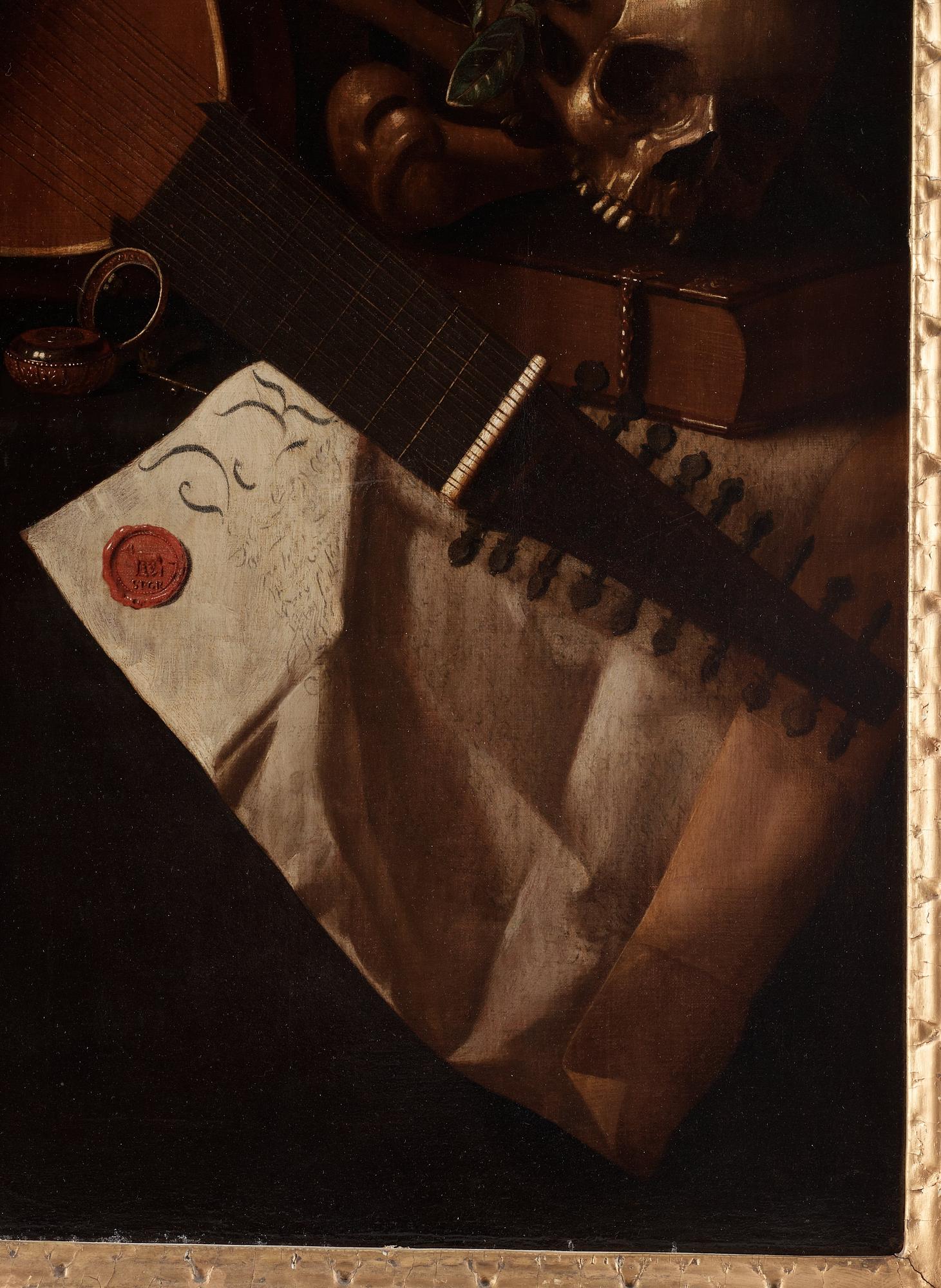

A vanitas still life with regalia, musical instruments, a reflecting imperial orb, a skull and bones and a charter group

Signed ‘P.v.Roestraeten’, lower left, and with monogram on the seal of the document. Period gilded and bronzed frame

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Probably sale Christie’s, London, July 30 1943, lot 77 (not illustrated); with B. Rapps Konsthandel, Stockholm, c. 1950; Private collection, Sweden, by 1990; sale London, Sotheby’s, December 13 2001, lot 19, colour ill.

Kirjallisuus

Fred G. Meijer, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Catalogue of the Collection of Paintings. The Collection of Dutch and Flemish Still-Life Paintings Bequeathed by Daisy Linda Ward, Oxford/Zwolle, 2003, pp. 29, 30 (fig. 13), 33, 34 (note 28) (measurements inverted).

Muut tiedot

Pieter van Roestraeten was born in Haarlem where before 1651 he was a pupil of Frans Hals for five years. He married Hals’s daughter in 1654. During the following years, he worked both in Amsterdam and in Haarlem. Between 1663 and 1666, Roestraeten moved to London where he remained active until his death. He was buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1700.

Reportedly, van Roestraeten was trained as a portrait painter, but no actual portraits by his hand are known today, apart from a genre-like self portrait. After his arrival in England, Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680), is said to have persuaded Roestraeten to give up portrait painting in exchange for an introduction to Lely’s clients as a still-life painter. For many of van Roestraeten's typical still lifes – ‘portraits’ of silver vessels, tea sets, etc. - the provenance can be traced to old English collections. Obviously he found a ready market in noble houses for this speciality. Apart from painting still lifes, van Roestaeten was also active as a genre painter, but he was much less prolific in that area.

This painting is one of the more prestigious compositions in Pieter van Roestraeten’s oeuvre and is among his larger paintings. The elaborate silver vase in the centre may well have been a pride possession of one of van Roestraeten’s patrons. In any case it was most likely the work of an English silver smith of the period. It occurs identically in one other of his still lifes and somewhat altered in a few others, but this appears to be the prime painting of its appearance. It is reminiscent of an even grander signed and dated still life from 1678, that was part of the collection at Chatsworth for as early as 1727, until it was sold in 1958. It may well date from around the same time as that piece. More than in most of his still life, Roestraeten has emphasized the vanitas theme here: life on earth is brief and only a preparation for the hereafter. The fading flowers, the skull and bones, the timepiece, the instruments that produce fleeting music, the symbols of worldly power, the coins, and the globe representing earth itself al allude to this. The vanity of the elaborate silver vessel, representative of worldly riches one cannot take into the grave, stands out here. By showing his own reflection in his studio in a shiny imperial globe hanging at top right, Roestraeten alludes both to his own fame as an artist as well as to the vanity (mirrors are associate with vanity) of his own existence.

Bukowskis are grateful to Fred G Meijer of the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, the Hague for cataloguing this lot.