Eric Grate

"Silvatica"

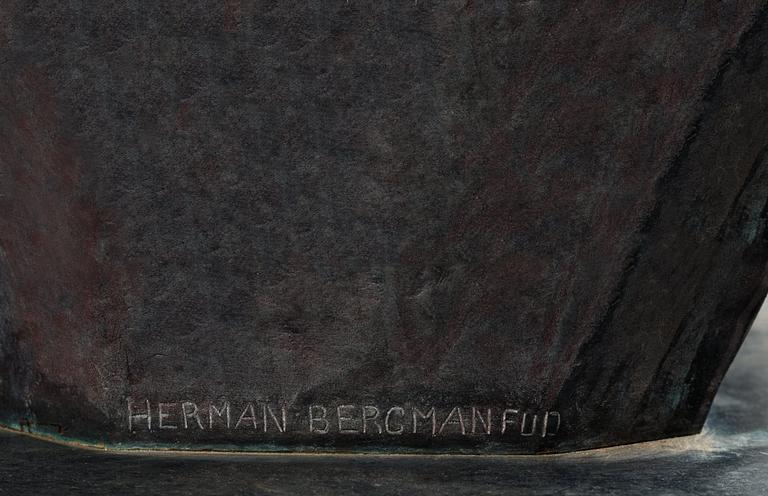

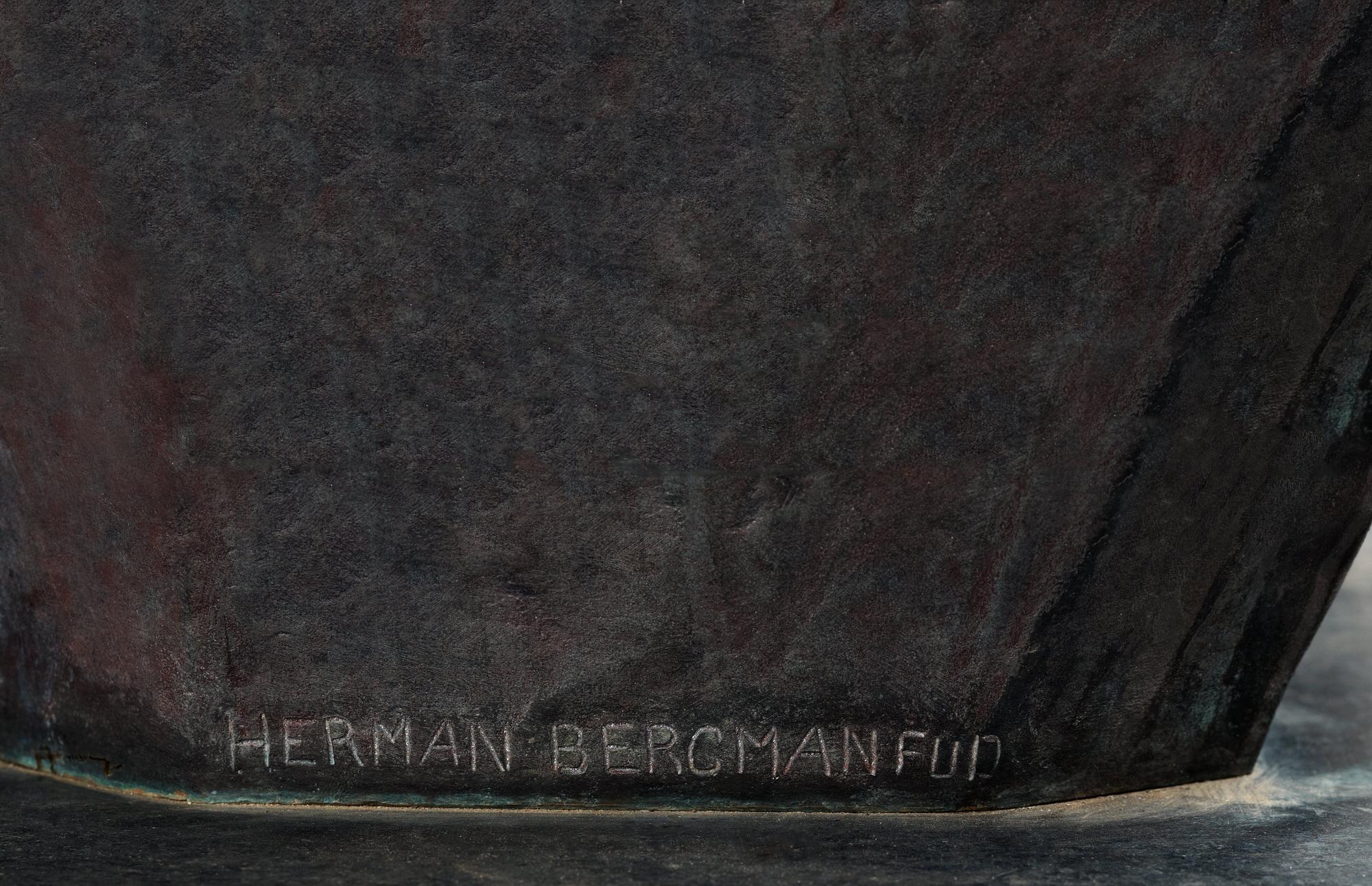

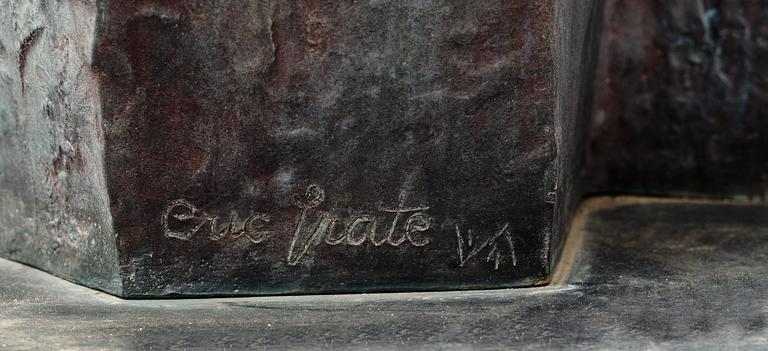

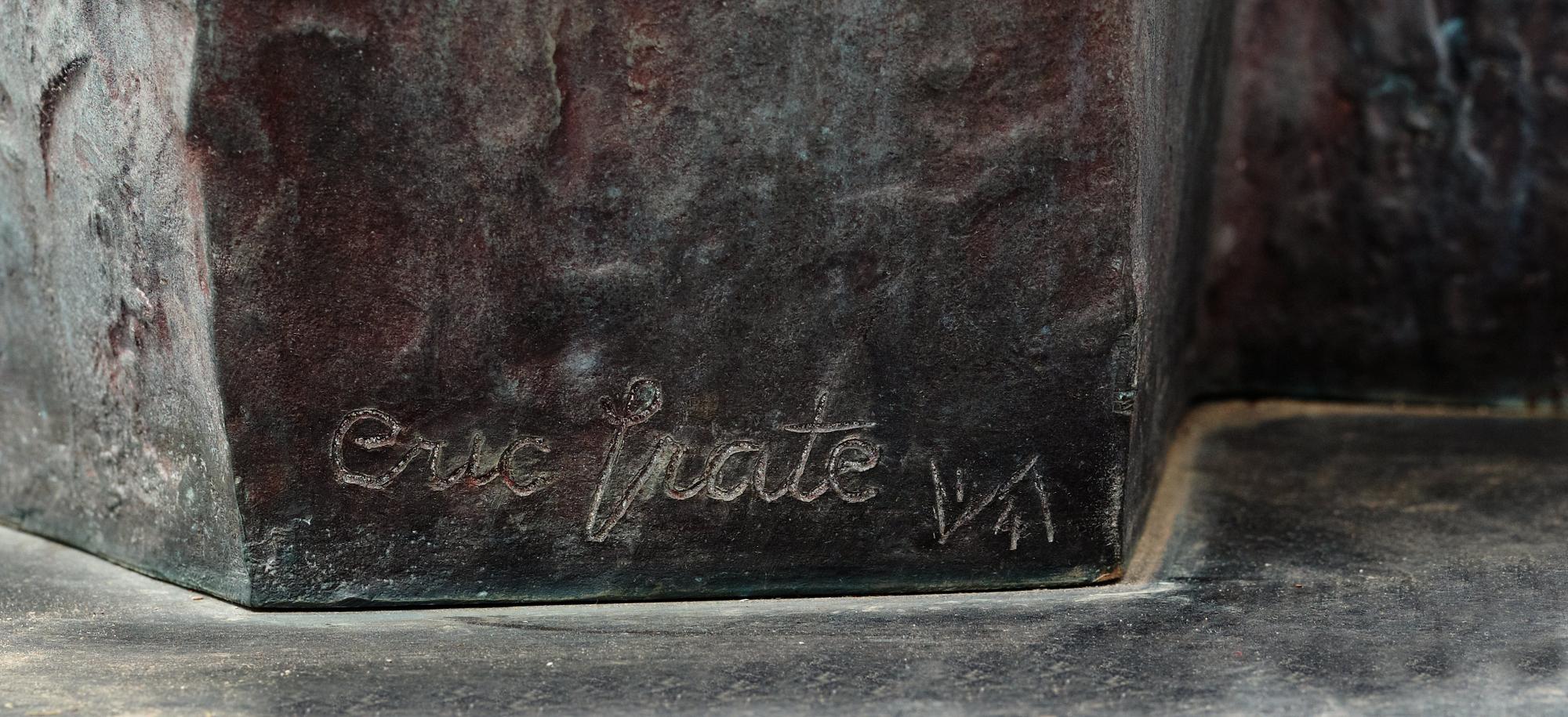

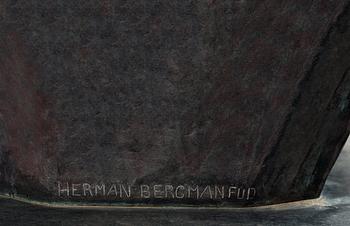

Signed Eric Grate and numbered 1/4. Cast in 1958-60. Foundry mark Herman Bergman Fud. Bronze, brown patina. Height 210 cm (82 5/8 in.), total height including stone base 218 cm (85 7/8 in.).

Note: If your online bid exceeds SEK 3 million, you will need a bank reference. Please contact our customer service to be cleared for this level of online bidding.

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Marabou Collection, Sundbyberg/Upplands-Väsby, Sweden (aquired directly from the artist in 1960).

Kraft Foods Sverige AB, Upplands-Väsby, Sweden.

Kirjallisuus

Henning Throne-Holst, "Ur Marabous byggnadshistoria", 1977, illustrated and mentioned p. 59 as well as illustrated in photo, p. 6.

Pontus Grate, Ragnar von Holten, "Eric Grate", SAK, 1978, illustrated and mentioned p. 111.

Ragnar von Holten, "Art at Marabou", 1990, illustrated and mentioned p. 19.

Muut tiedot

Eric Grate’s remarkable imagery always invites us in to his fantasy world. He respects nature’s own creations, but “sometimes plays God” by reshaping and combining nature and fantasy into new, astonishing objects that are both familiar and completely new, at one and the same time. Grate borrows fragments from nature and uses his unlimited imagination in unique ways. He himself devoted his works to the rocks, the plants, the wind, the water, the fish, the dog, the swallow, the insects, and to humankind, which has a bit of everything.

After studying at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1917-1920, Grate travelled to Italy and Greece, filling his sketchbooks with drawings of insects, plant fragments and details of ancient architecture, sculptures and pottery. Although these shapes are found in his sculptures throughout his career, Grate’s primary source of inspiration was probably African art, which he encountered early in life; Grate had the key to a small flat on Wallingatan in Stockholm, where the Ethnographic Museum kept its collections for a period in the 1910s. This was where Grate discovered African culture, and what he saw had such a magical allure that he was already familiar, when he arrived in Paris in 1924, with the world that Cubists such as Maurice Vlaminck had applied in their paintings. At the Trocadéro Museum in Paris, he found a vast amount of African artefacts that had been collected entirely randomly and unsystematically, and in the home of the sculptor Paul Guillaume (the first to produce an exhibition of African art) there was a large collection he could study. He bought his own first African object in a curiosity shop, a bateke fetish figure with bonga, a large belly of red clay that eventually crumbled to reveal its sinister contents, a snake’s head! Over time, he amassed a large collection of Africana. In the catalogue for the Liljevalchs exhibition “Eric Grate Six Decades” in 1976, the artist, friend and professor CO Hultén describes his encounter with the African collection in Grate’s studio:

“I am wandering around Eric Grate’s studio alone for a few hours. Back and forth between the studio and the room with his collection of African masks and sculptures. The file of studio rooms evokes a rare sense of pleasure and a remarkable association. There are sculptures everywhere. On tables, chairs, boxes, pulpits and modelling stands. They are reflected in a mirrored shelf, placed on window ledges, on the floor. Books on various subjects and from every corner of the earth. Many on Africa and African art.”

Eric Grate lived for nearly ten years in Paris, in 1924-1933, a seminal period in his life when he discovered the Surrealists Jean Arp, Paul Eluard and Tristan Tzara, and the sculptors Charles Despiau, Aristide Maillol and Constantin Brancusi. Initially, his ideal was classical sculpture, but as he persisted with diligent croquis drawing at Académie de la Grande Chaumière and Académie Colarossi, his style began to change. He was overwhelmed by all the Greco-Roman sculptures he had seen on his travels, and decided to be more restrictive and began to apply a measure of asceticism; under the influence of Maillol he began to sculpt serenely symmetrical, heavy female figures. He exhibited at the annual salons and managed to show as many as 19 sculptures at these prestigious meeting places for the Paris art scene. He also exhibited four times at the newly-opened radical “Salon des Tuileries” between 1927 and 1930. This Salon only showed artists by special invitation, and his co-exhibitors included the sculptors Bourdelle, Brancusi, Calder, Despiau and Zadkine. Thus, Grate was truly in the right place at the right time!

In 1929, Grate was invited by the Swedish Association for Art (SAK) to exhibit 43 sculptures and drawings at Liljevalchs Konsthall in Stockholm, and in 1930 he participated in Otto G Carlsund’s international exhibition of Post-Cubism at the Stockholm Exhibition. After his return to Sweden, the number of exhibitions intensified, and he won several public commissions, including “The Seasons” for the Government Offices in Stockholm, "The Fountain of Transformation” at the Marabou factory in Sundbyberg, and stage sets and costumes for the Royal Dramatic Theatre’s production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s “The Flies”. He took part in international biennials and worked intensely in a broad field, his style constantly evolving; he returned to shapes found in nature, picking out fragments and recreating the godlike creatures that became his theme after the Second World War.

Eric Grate appears to have had an insatiable curiosity; his travels around the world and his collecting of everything between heaven and earth constantly provided him with ideas for new forms, new combinations, an artistic approach inspired by different cultures but also by nature, fish bones, vertebrae, shells, stones, and an endless list of other objects. He succeeded in harmonising different period styles, identifying primeval echoes and combining them with metallic contemporary resonance. CO Hultén recalls from his encounters with Grate that his most characteristic trait was “his demand on meticulously processing and realising his intentions”.

Eric Grate’s relationship with Marabou dates back to the 1940s when he created a relief commissioned by the chocolate factory’s dynamic and art-loving director, Henning Throne-Holst. The relief had only just been installed in Sundbyberg when he received a new commission. This time, Throne-Holst wanted Grate to design a fountain to be placed in front of the canteen. He worked on “The Fountain of Transition” in 1943-1956, a magnificent and monumental piece with trickling water, measuring 330 cm in diameter. A warm friendship grew between Henning Throne-Holst and Eric Grate, leading to the acquisition in 1960 of yet another sculpture, the remarkable “Silvatica”.

This monumental piece is among the now-famous plant-inspired sculptures that Eric Grate devoted himself to in the late-1950s. “Silvatica”, whose name is a variant of the Latin word silva, forest, is both a forest lily and a seated woman. Graceful and sensual, she is swathed in petals, with a torso, arms and legs of stylised leaves. In the book “Erik Grate” published by SAK in 1978, Pontus Grate and Ragnar von Holten write:

“a Nordic Daphne from the forests of Carl Linnaeus. As she unfolds her leaves and reveals her beauty, she is transformed into an enticing sexual being. Her seated position becomes a heavy, sensual repose on the ground. But the spiralling opened plane and the finely-chiselled, concave silhouettes lift slowly and gracefully in a flighty, provocative dance of veils.

With its abstract design, its sharp and well-defined play of lines and its innovativeness, it nevertheless harks back to the naturalist lyricism that Grate developed in the 1930s and to his life-long passion and proximity to African art. “Silvatica” is one of Eric Grate’s finest sculptures, which, in many ways, sums up his entire oeuvre.