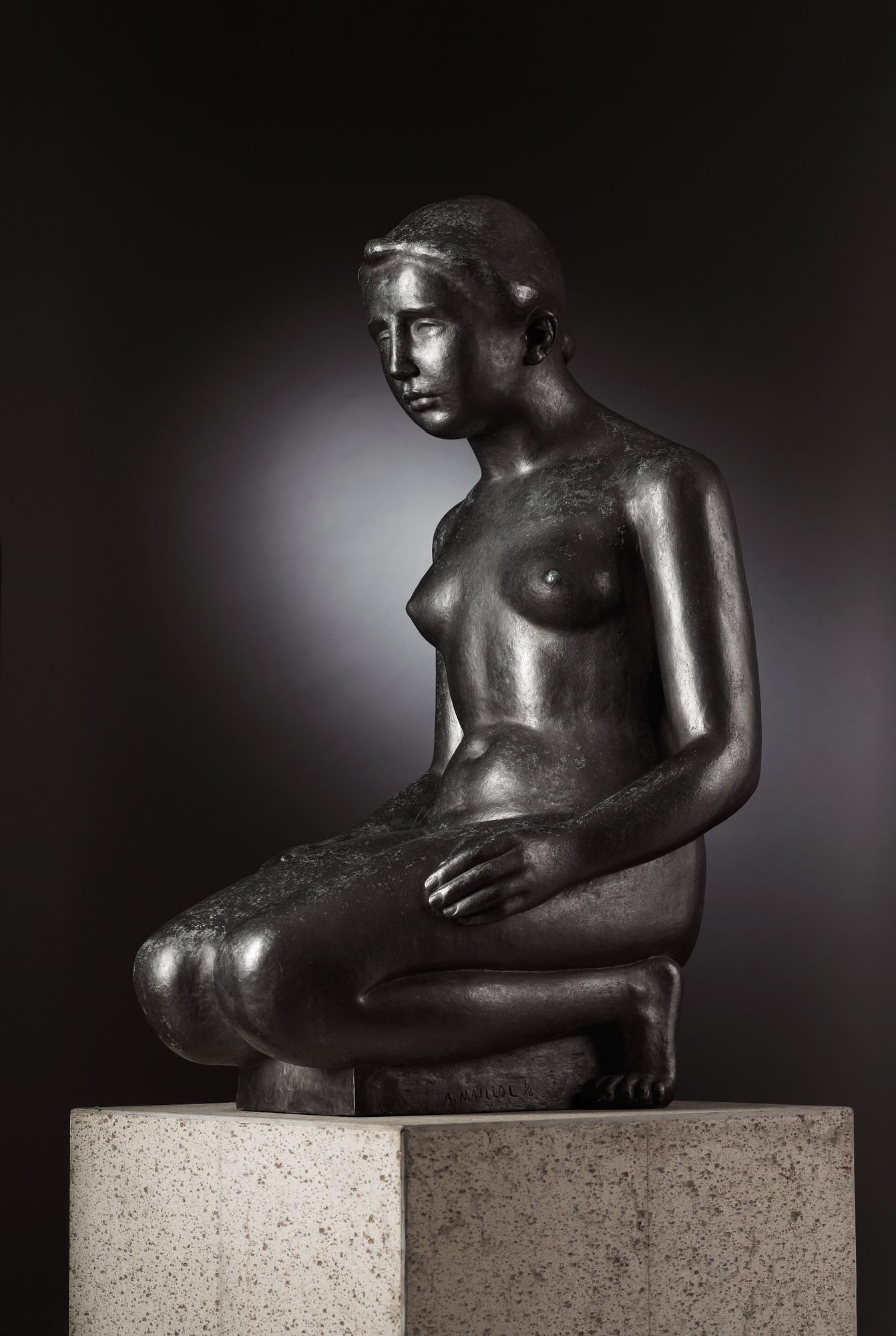

Aristide Maillol, jälkeen

"Jeune fille agenouillée"

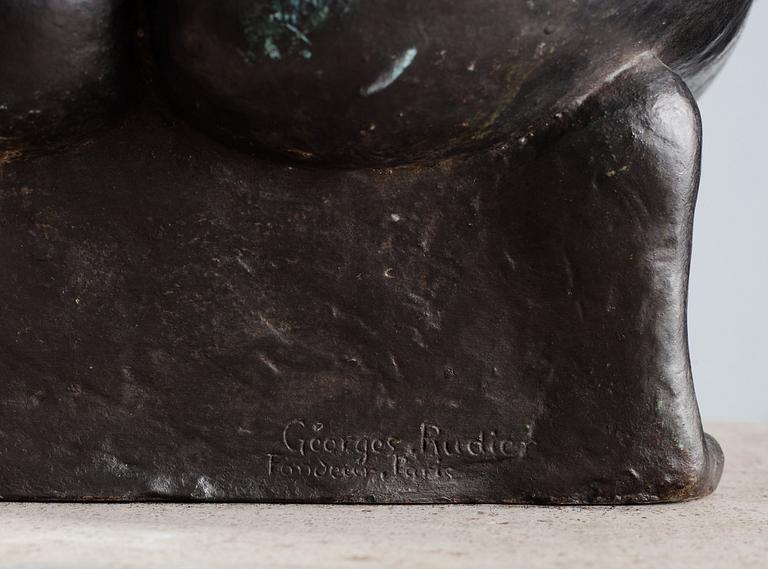

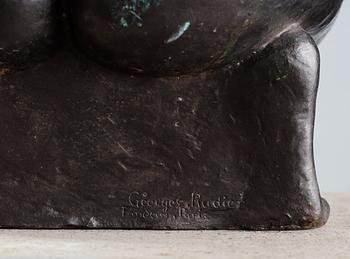

Stamped signature A. Maillol and numbered 1/6. Cast during 1950s. Foundry mark Georges Rudier Fondeur, Paris. Bronze, dark patina. Height 85 cm (33 1/2 in.), total height including stone base 165 cm (65 in.).

Note: If your online bid exceeds SEK 3 million, you will need a bank reference. Please contact our customer service to be cleared for this level of online bidding.

Täydennyslista

After the death of Maillol the sculpture was cast in an edition of 6 at George Rudier Foundry in Paris, this was commisioned by Mons Fabiani, heir to Ambroise Vollard (art dealer of Maillol). The present lot is number 1/6. Another cast is in the collecton of the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture garden in Washinton D.C.

Correct estimate 800.000 - 1.000.000 SEK / 92.950 - 116.150 EUR

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Svensk-Franska Konstgalleriet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Marabou Collection, Sundbyberg/Upplands-Väsby, Sweden (acquired from the above in 1956).

Kraft Foods Sverige AB, Upplands-Väsby, Sweden.

Kirjallisuus

John Rewald, "Maillol", 1939, compare p. 102 in smaller version (under the title "Knieendes Junges Mädchen").

Waldemar Georg, "Aristide Maillol, et l'âme de la sculpture", 1964, compare p. 126-127, called "Jeune Fille agenouillée".

Ragnar von Holten, "Art at Marabou, a short guide", 1974, illustrated and described p. 34.

Ragnar von Holten, "Art at Marabou", 1990, illustrated and mentioned p. 33.

Bertrand Lorquin, "Aristide Maillol", 2002, compare similar composition, p. 51 and this composition, without arms, p. 186.

Muut tiedot

The plaster model of "Jeune fille agenouillée"conceived in the beginning of 20th century. Bought by Ambroise Vollard, famous art dealer in Paris. After the death of Maillol the sculpture was cast in an edition of 6 at George Rudier Foundry in Paris, this was commisioned by Mons Fabiani, heir to Ambroise Vollard (the art dealer of Maillol). The present lot is number 1/6. Another cast is in the collecton of the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture garden in Washinton D.C.

Receipt from Svensk-Franska Konstgalleriet, Stockholm enclosed. Bukowskis will like to thank Olivier Lorquin, Président de la Fondation Dina Vierny-Musée Maillol, Paris for information about the sculpture.

“I seek to express the impalpable”

With exalted tranquillity, Maillol’s genuflecting girl greets us. Her body is resting peacefully, in perfect, silent, harmonious equilibrium. She does not give the impression of wanting to tell us anything; on the contrary, she is in her own closed, timeless universe.

Aristide Maillol began sculpting fairly late in life, when he was already in his forties. By that time, he had been battling with his art for two decades, under great adversity and poverty. As a young man, he had to apply repeatedly before being accepted by the École des Beaux-Arts. His passion was painting, but he enjoyed no success in the field. In the 1890s, he became friends with Paul Gauguin, who had a seminal influence on Maillol’s artistic career. With encouragement from Gauguin, he began making tapestries that won him great acclaim, and he could even assign some of the work to weavers. Just as success seemed within reach, he was afflicted with a temporary impairment of his eyesight, probably caused by strain. This forced him to abandon weaving in favour of a more tactile three-dimensional artistic medium. Despite having only sporadically studied sculpture and having only the most elementary skills in the art, he soon found his own unique style, and astonishingly soon revealed a mature, fully-developed artistic ability. Within a couple of years, he had focused on the subject matter that was to preoccupy him for the rest of his life - variations on the female body. Maillol represented something new and broke away completely from 19th century sculpture. His works cleared the path for the emerging modern art.

In 1900, Maillol was discovered by the prominent art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who was an important patron on the French art scene then. He exhibited and supported a large number of artists, including Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso and Paul Gauguin. It was Vollard who organised Maillol’s first solo exhibition at his gallery on Rue Laffitte in Paris in 1902. Maillol’s sculptures immediately aroused the interest and admiration of his artist colleagues and art lovers in general. In only a few years, Maillol had become a success, and his dire financial situation improved thanks to a wealthy patron. But he was still controversial or unknown to the broader public. The sculpture in our auction stems from this early period, originally in a plaster version purchased by Vollard. “Jeune fille Agenouillée”, is an exquisite example of Maillol’s early 20th century works, with its artless simplicity, grace and archaic style.

“I find form pleasing and that is what I create; but for me it is only a way of expressing the idea. It is ideas that I am looking for. I use form to reach what is without form. I strive to convey what is not palpable, what cannot be touched.” Aristide Maillol

The 19th century sculptural tradition was largely based on realism, with a great measure of narrative, which included the use of metaphors, symbols and attributes. At the turn of the century, Auguste Rodin was by far the dominating sculptor. His vigorous works are characterised by contorted, almost tortured shapes, and can be seen as combining two of the prevailing tendencies at the time, realism and symbolism. Most young sculptors in the late-1800s were influenced by his art and his teachings. Perhaps, Maillol’s distinctive art would not have come to expression had he taken up sculpture in his youth and thereby possibly been taught by Rodin. Maillol’s simplified, static sculptures made a clean break with the 19th century. With their silent, closed, massive forms, they defy any attempt at interpretation. In the late-1800s, Maillol had come into contact with the Nabis group of artists, whose members included Maurice Denis, Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard. Inspired by Gauguin’s innovative theories, they were opposed to impressionist naturalism. They were more interested in the artist’s own inner visions than by observing nature. ”A picture, before being a battle horse, a nude, an anecdote or whatnot, is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.” This was said by Maurice Denis, and presages modern art. It can also in some sense be applied to Maillol’s sculptures. His aim was that art should not be descriptive or avail itself of metaphors, but that it should represent a striving towards a simplification of form, in order to express the synthesis of the object.

“When nations grow old […] art gets complicated and soft. We have to try to become young again and work in all innocence. That’s what I am trying to do. And that’s why I’ve had some success, because this is a period when people are trying to return to the primitive. I myself work as if nothing ever existed, as if I had never learnt anything. I am the first ever to make sculpture.” Maillol

Naturally, Maillol was not unaware of art history or the present times. He often visited museums and was an avid reader. But he did not find his inspiration among contemporary sculptors, and was more fascinated by ancient sculpture. There was a growing ideological tendency to regard Western civilisation as degenerate, and Maillol admired early Hellenic sculptors, especially Phidias. He considered late Hellenic sculpture to have lost its stringency. Of even greater significance to Maillol was non-European art – specifically the Indian, Chinese and Japanese sculptural traditions. Art from Africa, India and the Khmer Empire fascinated him. It is easy to see how he was captivated by the terse Egyptian portrayal of the human body.

Aristide Maillol had deep roots in his birthplace, Banyuls-sur-Mer in Catalonia, just north of the Spanish border. In his heart and soul, he was a Catalan, and he lived most of his life there. He married a local woman, Clotilde Narcisse. As a child, his parents left him with a spinster aunt, and he grew up without his mother. It is possible that this had a lasting impact on him, and that his fascination for the female body originated in his longing for his mother. Maillol saw the female body as a cathedral or temple, and maybe even as a refuge. Catalan women, with their robust bodies, came to influence his style of sculpting and provided a lifelong source of inspiration. He was indifferent to individual traits, however: “I am not interested in particulars, what interests me is the general idea.” His goal was the absolute, through simplification and an emphasis on mass and volume, rather than on the sensual portrayal of women’s forms. “I strive for architecture and volumes,” Maillol explains, “Sculpture is architecture, a balancing of masses, a tasteful composition. It is difficult to attain this architectural aspect. I try to render it the way Polycletes succeeded in rendering it. My point of departure is always a geometrical figure – a square, a rhomb, a triangle, since they are the figures that are most stable in space.”

Maillol died in 1944, due to injuries sustained in a car accident. He was 83 then and had been active in many artistic disciplines, including painting, wood carving, pottery, book illustration and tapestry weaving. It was as a sculptor, however, that he made his most profound mark on art history. He performed numerous public commissions and over time won both national and international fame.

“Jeune fille Agenouillée” is an excellent example of Maillol’s outstanding talent. With its robust yet graceful shapes, it conveys to us how the weight of the mass is perfectly balanced. The surface does not describe skin, but is an integrated part of the entire sculptural material. Innocent, absolutely immobile and introspective, she gives a timeless impression. In this way, she is emblematic of Maillol’s contribution to art: a hotbed, not to say a necessary condition, for what was coming, groundbreaking abstraction and modern art. Many sculptors were to follow in his footsteps, including Henri Laurens, Henry Moore and Jean Arp. Aristides Maillol’s renewal of the art of sculpture is a synthesis between ancient art and future abstract art. In this sense, his sculptures form an interface linking the origins of art with its future promise.