Bukowskis presents LARS NORÉN – THINGS

LARS NORÉN – THINGS

Intro Lars Ring, cultural journalist

Lars Norén has unexpectedly and suddenly passed away. And so his project to write himself into effacement has been thwarted. The intention was, by continuing to incessantly write, to examine how ageing makes words and perspectives disappear. To – in practice – register how memory is erased. Instead, a ruthless silence has suddenly appeared – one that has left the cultural scene almost speechless when faced with the task of connecting with his enormous production.

Lars Norén was a literary giant – IS a giant. His plays will always remain IN THE PRESENT through new performances. The works now live their own lives, increasingly disconnected from the ‘biographical’, from the time when they were birthed and from the moral upset that came to accompany some of them.

The legacy of Lars Norén is great and important. He gave a few generations, born during the late 20th century, a manifest subconscious and a superego revealed. Lars Norén made his precipitous diagnoses in a time when psychoanalysis had become available to all, when time had become a post–capitalist labyrinth filled with a sense of not belonging, and where violence was becoming increasingly anonymous and brutal. He defined the alienation that characterises our time. He wrote me, he wrote us.

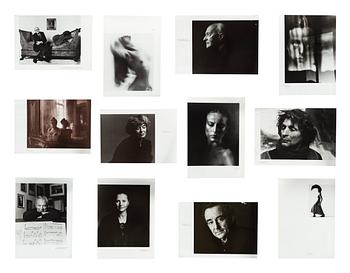

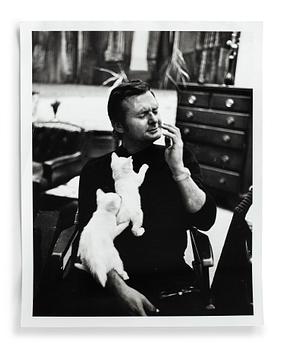

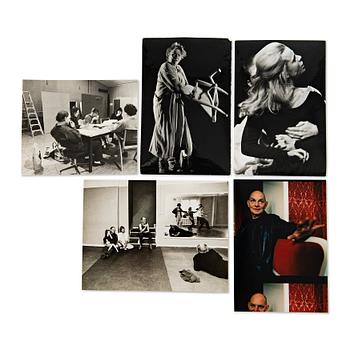

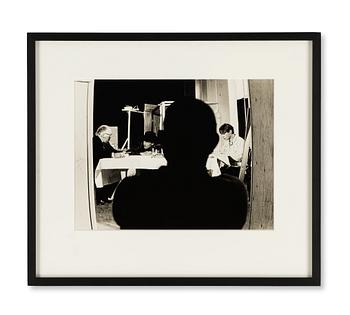

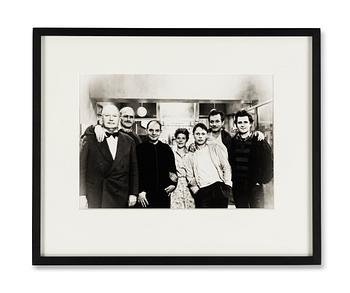

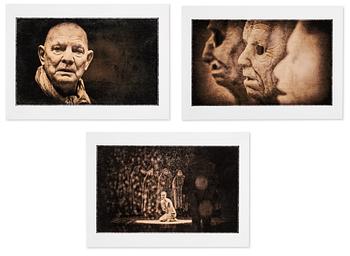

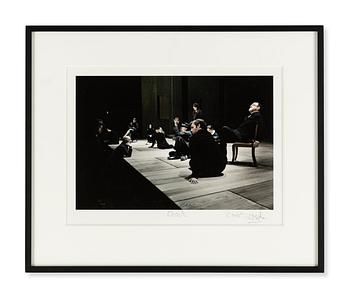

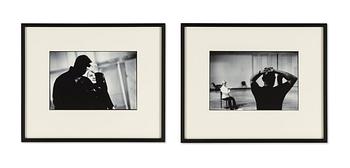

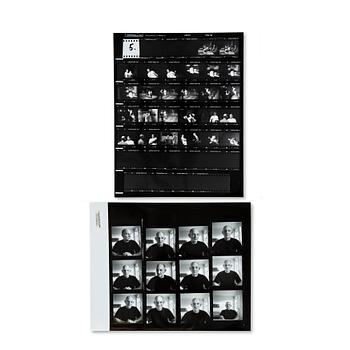

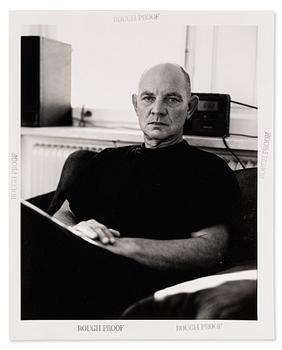

Photography Sara Mac Key

” ... mina barn får ta tio femton

saker var när jag dör ...

ett bestämt antal klädesplagg och

sedan sälja resten ... ”

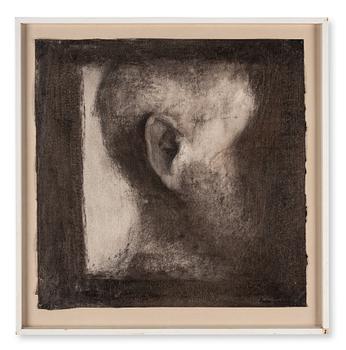

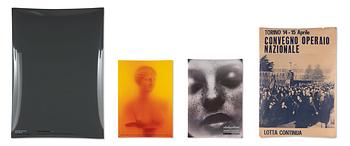

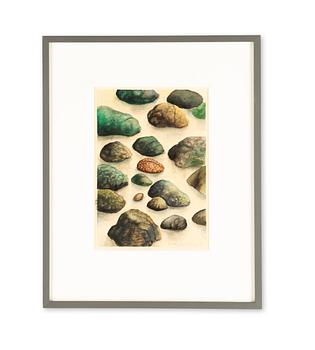

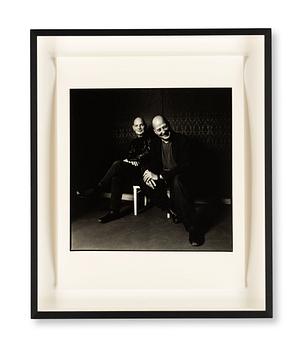

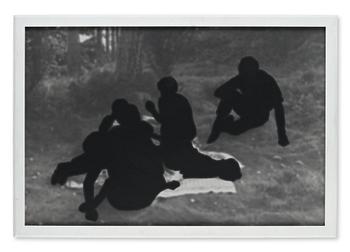

Maria Miesenberger, photograph signed and numbered 3/3 on verso. Estimate 100 000 SEK.

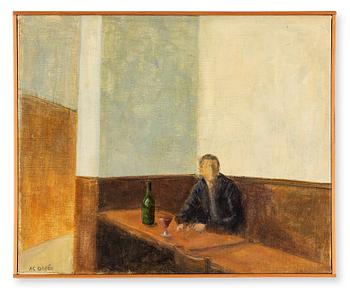

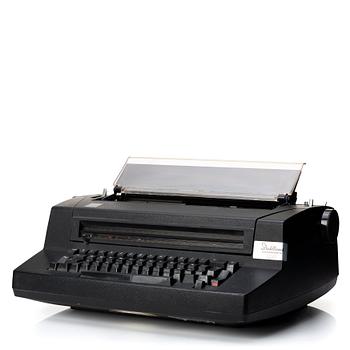

Many people associate Lars Norén with bourgeois quartets, or with his breakthrough plays and their depictions of the family hotel in the southern Swedish village of Genarp. On one level he was deeply marked by this hotel, by its anonymous rooms, constant guests, and the prevailing sense of departure. This is also what his home looked like. The flat on Östermalmsgatan, which I once visited for an interview, was desolate. There was a study, with an electric typewriter with a typeball, on which he, almost compulsively, wrote and rewrote his manuscripts. There was his elegant bicycle, which had been given its own room; another room had one of the iconic Le Corbusier armchairs in it. He was an aesthete when it came to things. Practically all of his interiors were therefore almost symbolically significant. There was only the carefully selected, that which would not hinder his creative flow: the echo of memories, conversations and other literature. The echo of time.

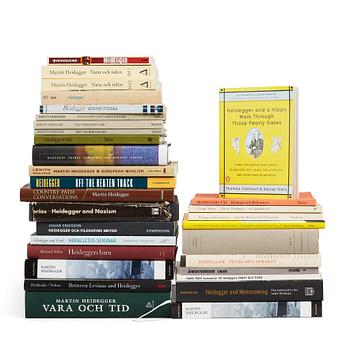

Lars Norén WAS a typewriter. His craft embodied the role of the dramatist and the corrective red pen. His early plays were almost as long as the bible, whereas the later series of ‘Terminal’ plays are short – like spotlights on existential moments. His words were framed by other work, which served as structure and limitation. The inspiration came from a few distinct sources. Aeschylus, in particular his Oresteia with its bloody conflicts between parents and their children; Eugene O’Neill, whose Long Day’s Journey into Night he saw performed at Dramaten in 1956; and Edward Albee, whose marital wrestling matches were based on Strindberg’s work. Beckett represented a true kinship when it came to the sparseness of words in Norén’s later works. And his diaries that became a breathing space, a way of writing himself free of cliques and contexts by going on verbal attacks. A kind of Proustian search for a time that is, yet is also lost, as well as fiction. Filled with literary, subjective truth. A contemporary story of how someone’s mind works.

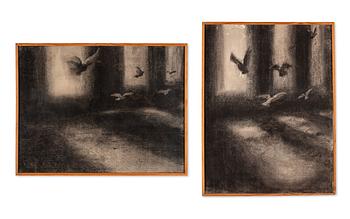

I am thinking of Lars Norén. I see his study in front of me. I hear the tapping from the typewriter, the silence in between the words. I understand the strong will, whatever the cost, to have integrity. To break free, be unfaithful to the general consensus, and to have the bravery to depict the uncomfortable. The writing follows two parallel lines. The biographical; with the move to Stockholm and the bourgeoisie that he follows to their watering holes – the Swedish archipelago, the Danish west coast or Tuscany. Yet at the same time as he describes these families in detail, their rooted frustrations and the deep traumas that are ruining their lives, he also writes about people that are on the outside of society. Early in his career, Norén wrote about mental hospitals, about victims of the Balkan wars, about the Romani people, about the dispossessed, and about drug abusers. He gives these ‘rejects’ words, background. It is HUMANS that have fallen or been cast out – not a pariah but language. Through the years he has also approached group violence as a mechanism in depictions of what happens in prisons, and in memory of the Holocaust. Relentlessly he circles around that which is truly horrific.

IBM Selectric Typewriter 670X. Estimate 5 000 SEK. A 20th century lacquered metal desk. Estimate 6 000 SEK.

Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret & Charlotte Perriand, "LC4", Cassina, Italien. Estimate 20 000 SEK.

” Trädgården mellan 10 och 13. Sedan sprang jag. Pumpade cyklarna, var tvungen att ta Bianchin. Den är inte bra på grusvägar. ”

A Bianchi road racer bicycle, Italy circa 1980’s. Estimate 5 000 SEK.

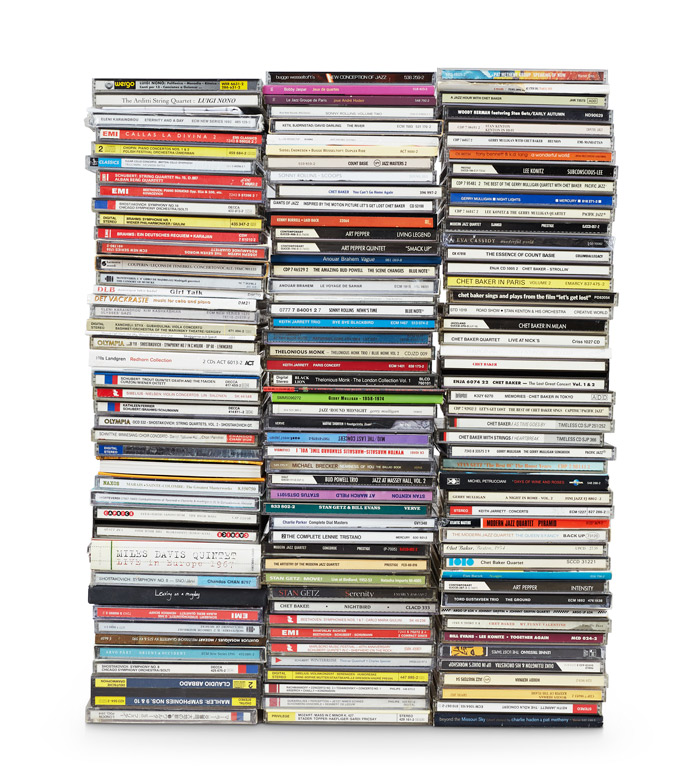

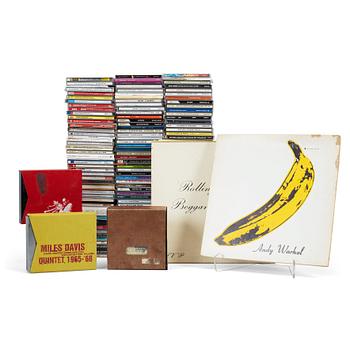

” Jag har lyssnat på Maria Callas, Sofia G, en annan ryss, som har skrivit ett stycke som heter Styx, Beethovens andra och sjunde symfoni och en del annat. Håller på att lyssna igenom hela min cd–samling. Det tar flera år. ”

The complete music collection of Lars Norén, circa 480 pieces. Estimate 5 000 SEK.

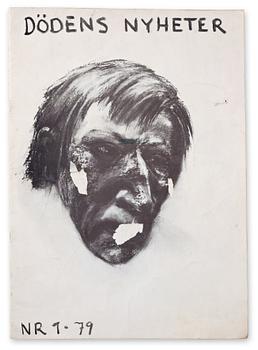

Lars Norén was controversial. He wrote the play 7:3 for a group of prisoners, of which a few later went on to commit terrible crimes. The intention was to candidly describe the racism and Nazism that is spreading in our detention centres. To force the audience into taking a stand. Depicting reality should never result in wanting to blame the messenger. Norén allowed us to come face to face with destitution, with violence, but above all, allowed us to understand what had happened. Plays such as Kyla – about the murder of the teenage boy John Hron – and 20 November – depicting how a young man becomes a terrorist – are brutally affecting.

He was one of the great Europeans. Just how significant he was, we have probably yet to fully understand. The Norénian landscape moves between the seemingly idyllic and the abysses of the soul. Again and again, he pulls the rug out from under our feet, with his sudden, absurd gallows humour. A text by Norén is always a minefield.

Lars Norén has exited time, but his texts remain timeless. Many of the plays have only been performed once. Some have never been performed. It is time to freely interpret his dramas, perhaps more loaded than the usual Swedish psychological realism. Now the future will mourn, analyse, and write dissertations. Like Strindberg, his language has an incredible energy that stops for nothing. Like Bergman he battles, not with God, but with the beast within us all. He wrote to find the pain, to find truths untainted with the lies of language. Now we will sit on his chairs, think about why he came to love concrete, and be unnerved by all his depictions of the hells we create for each other. A lot remains to be done. Lars Norén is not finished with us yet.

When is the viewing & auction?

Viewing 13 — 17 October, Berzelii Park 1, Stockholm.

Online auction 8 – 17 October.

Catalogue online 8 October.

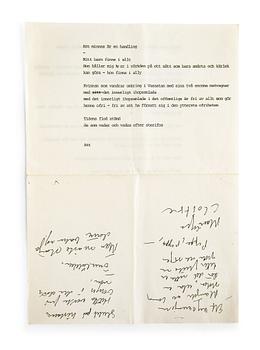

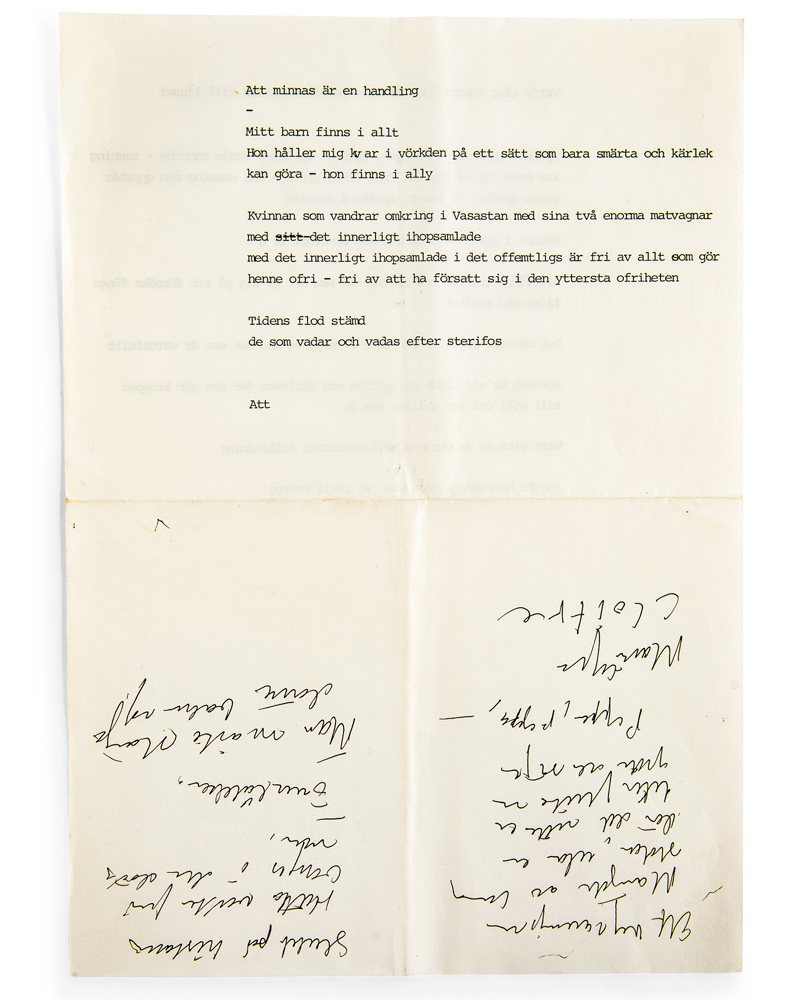

Lars Norén, typewritten and handwritten note. One sheet A4, double sided. Estimate 1 500 SEK.

Bid on the objects

Hammer price

57 000 SEK

Estimate

5 000 SEK

Hammer price

10 000 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

8 200 SEK

Estimate

4 000 SEK

Hammer price

5 200 SEK

Estimate

800 SEK

Hammer price

6 800 SEK

Estimate

2 000 SEK

Hammer price

21 000 SEK

Estimate

15 000 SEK

Hammer price

47 000 SEK

Estimate

20 000 SEK

Hammer price

6 000 SEK

Estimate

4 000 SEK

Hammer price

23 000 SEK

Estimate

10 000 SEK

Hammer price

10 100 SEK

Estimate

6 000 SEK

Hammer price

3 700 SEK

Estimate

3 000 SEK

Hammer price

17 500 SEK

Estimate

6 000 SEK

Hammer price

7 700 SEK

Estimate

8 000 SEK

Hammer price

136 000 SEK

Estimate

100 000 SEK

Hammer price

22 550 SEK

Estimate

8 000 SEK

Hammer price

23 000 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

7 800 SEK

Estimate

5 000 SEK

Hammer price

11 600 SEK

Estimate

8 000 SEK

Hammer price

9 153 SEK

Estimate

4 000 SEK

Hammer price

8 800 SEK

Estimate

8 000 SEK

Hammer price

6 800 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

5 700 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

14 500 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

6 200 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

7 200 SEK

Estimate

2 000 SEK

Hammer price

34 000 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

11 600 SEK

Estimate

800 SEK

Hammer price

10 500 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

38 000 SEK

Estimate

5 000 SEK

Hammer price

6 000 SEK

Estimate

800 SEK

Hammer price

6 600 SEK

Estimate

4 000 SEK

Hammer price

12 500 SEK

Estimate

4 000 SEK

Hammer price

13 700 SEK

Estimate

3 000 SEK

Hammer price

9 600 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

14 500 SEK

Estimate

4 000 SEK

Hammer price

5 602 SEK

Estimate

500 SEK

Hammer price

12 500 SEK

Estimate

3 000 SEK

Hammer price

6 200 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

12 000 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

11 600 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

10 655 SEK

Estimate

2 000 SEK

Hammer price

18 000 SEK

Estimate

3 000 SEK

Hammer price

20 000 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

10 100 SEK

Estimate

3 000 SEK

Hammer price

5 800 SEK

Estimate

4 000 SEK

Hammer price

3 800 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

5 800 SEK

Estimate

3 000 SEK

Hammer price

4 200 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

5 000 SEK

Estimate

2 000 SEK

Hammer price

19 000 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

Hammer price

7 400 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

38 000 SEK

Estimate

3 000 SEK

Hammer price

8 800 SEK

Estimate

2 000 SEK

Hammer price

15 500 SEK

Estimate

2 500 SEK

Hammer price

9 200 SEK

Estimate

6 000 SEK

Hammer price

8 401 SEK

Estimate

500 SEK

Hammer price

11 600 SEK

Estimate

1 500 SEK

For more information regarding the upcoming auction Contact category specialist

Stockholm

Björn Extergren

Head of Consignment and Sales Department, Fine Art. Specialist Antique Furniture, Decorative Arts and Asian Ceramics

+46 (0)706 40 28 61

Stockholm

Eva Seeman

Chief Specialist Modern and Contemporary Decorative art and design

+46 (0)708 92 19 69