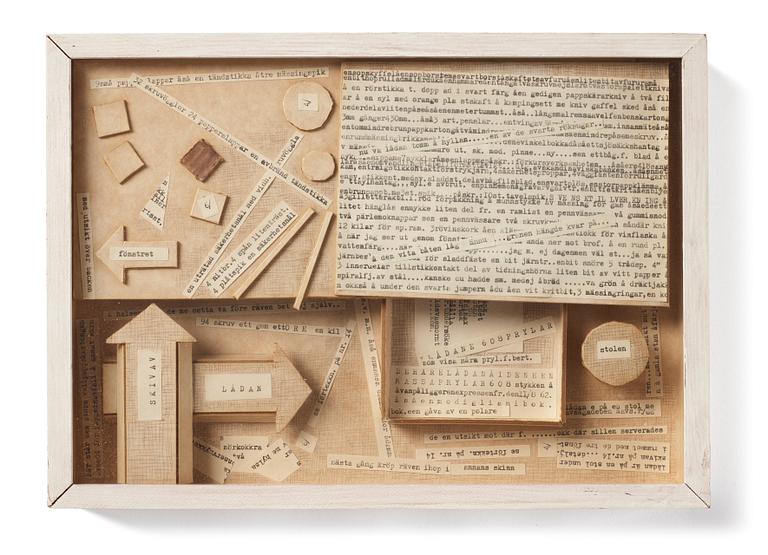

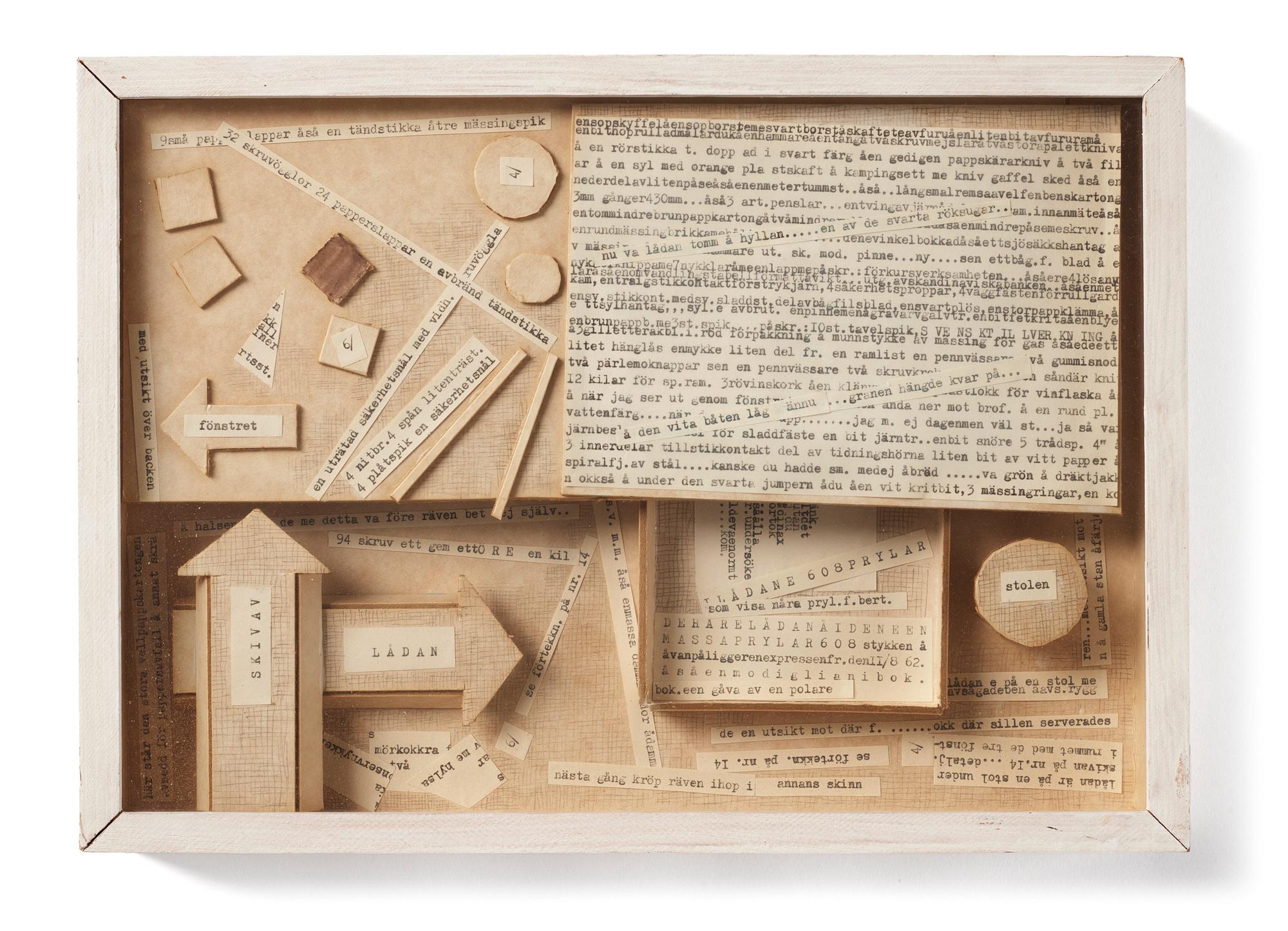

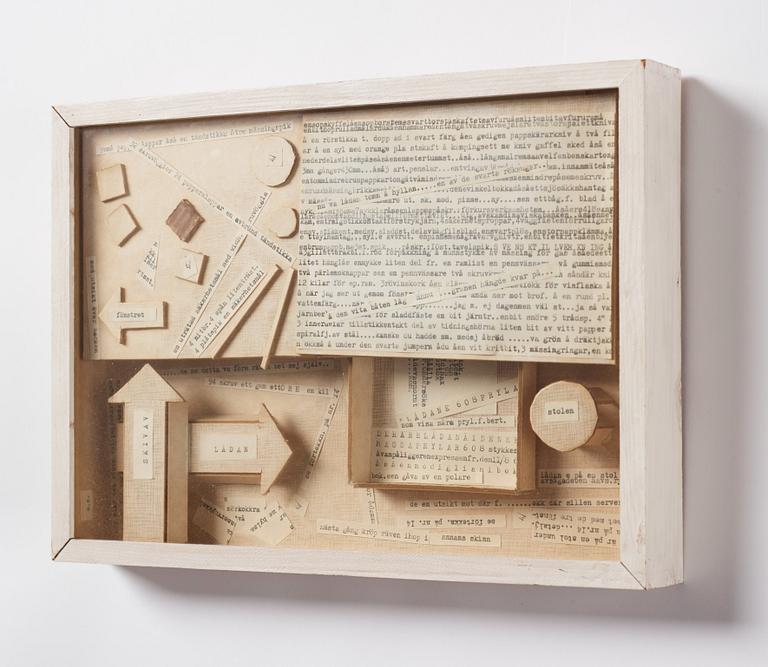

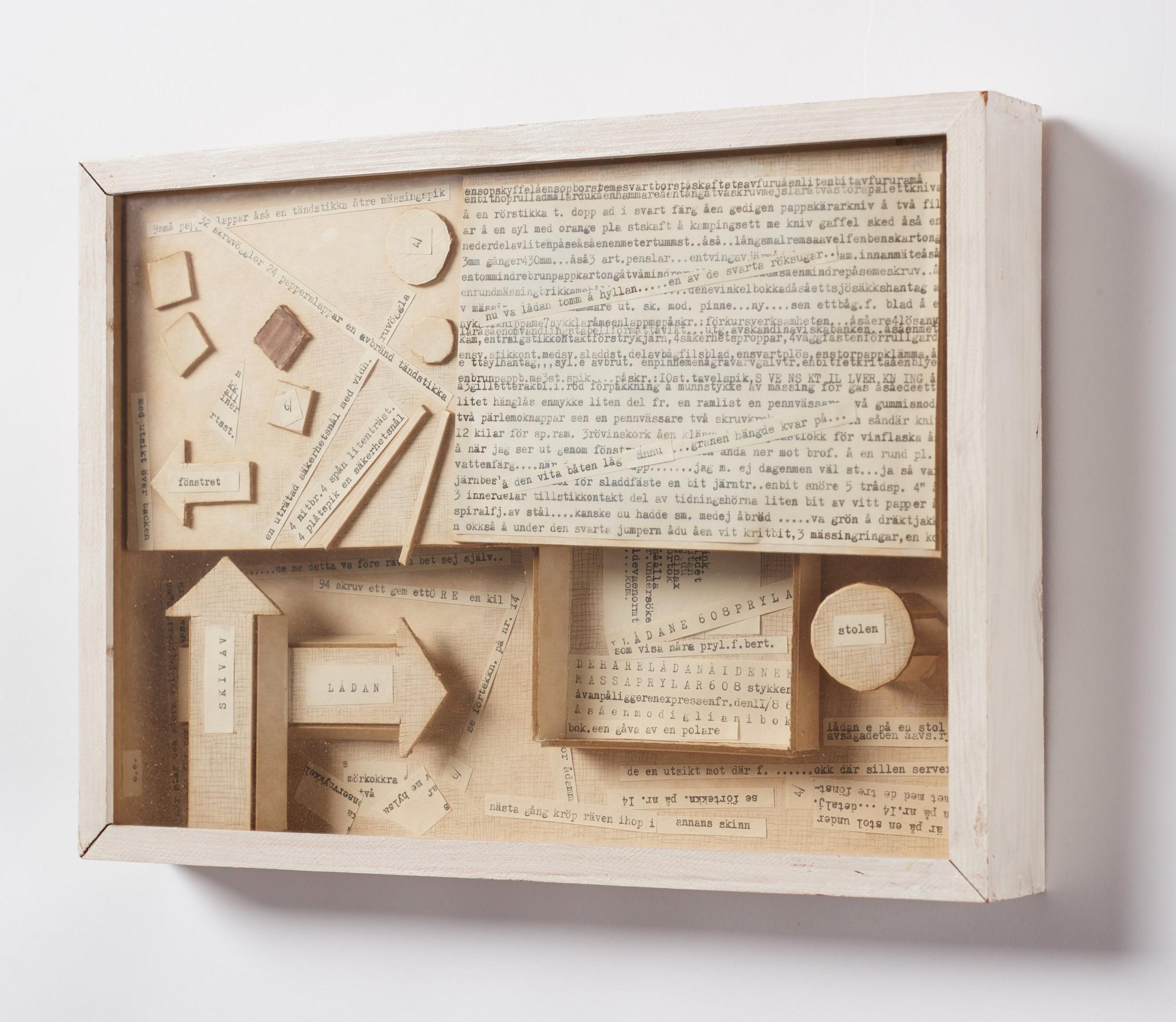

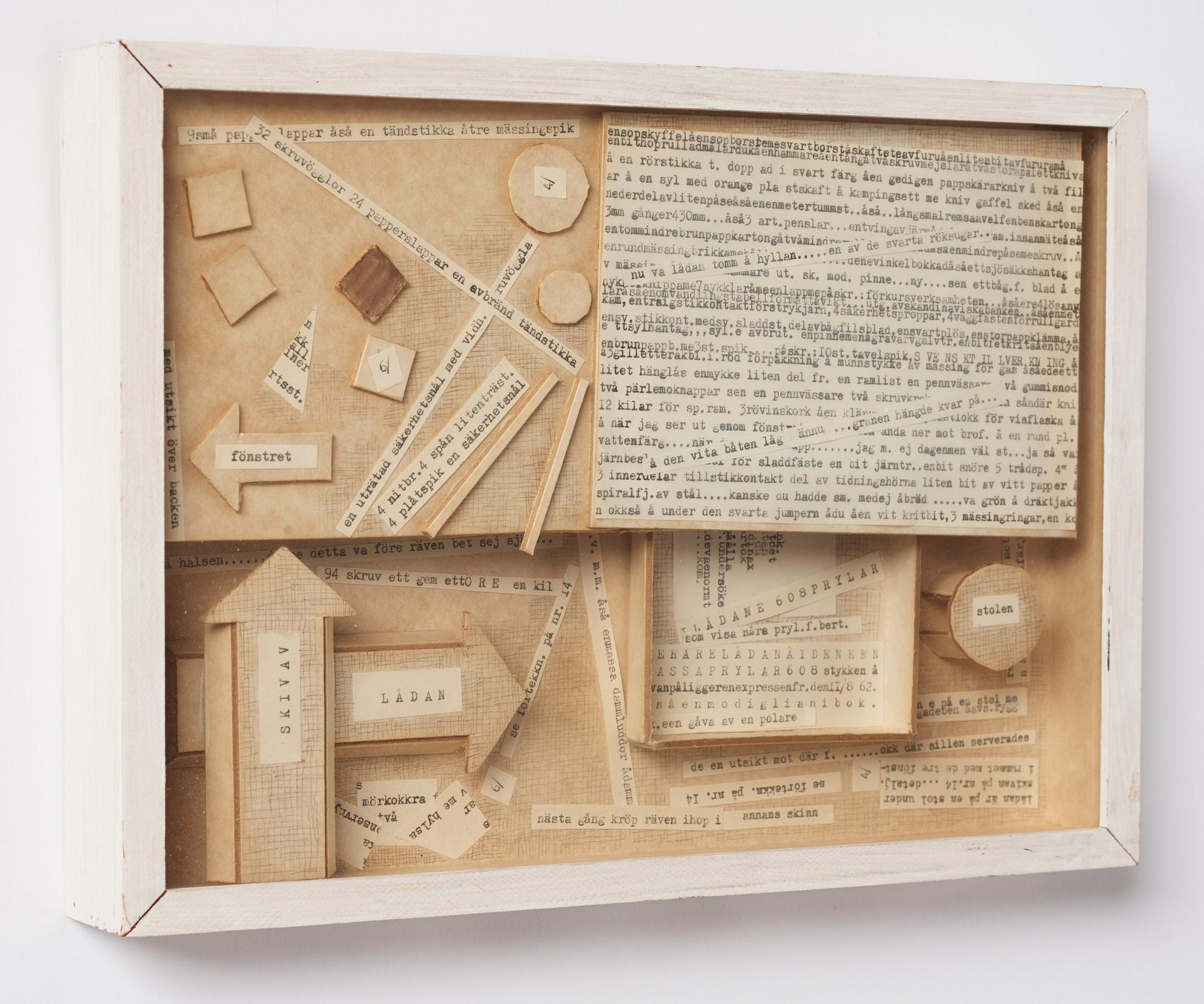

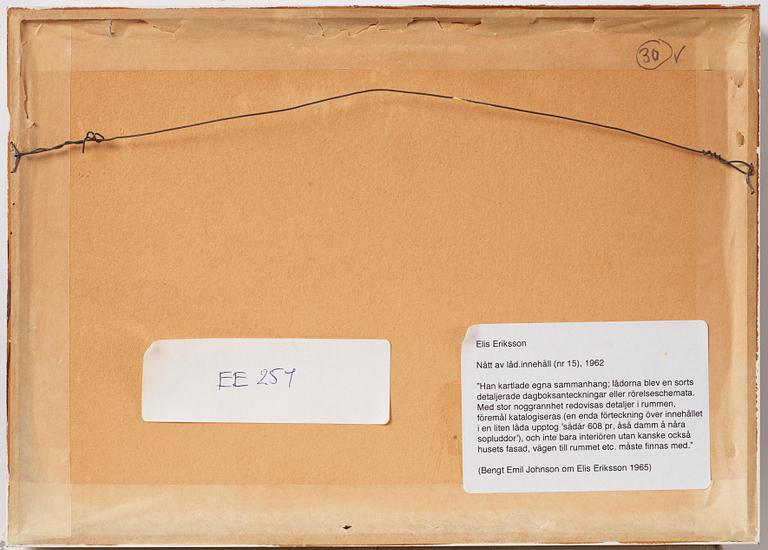

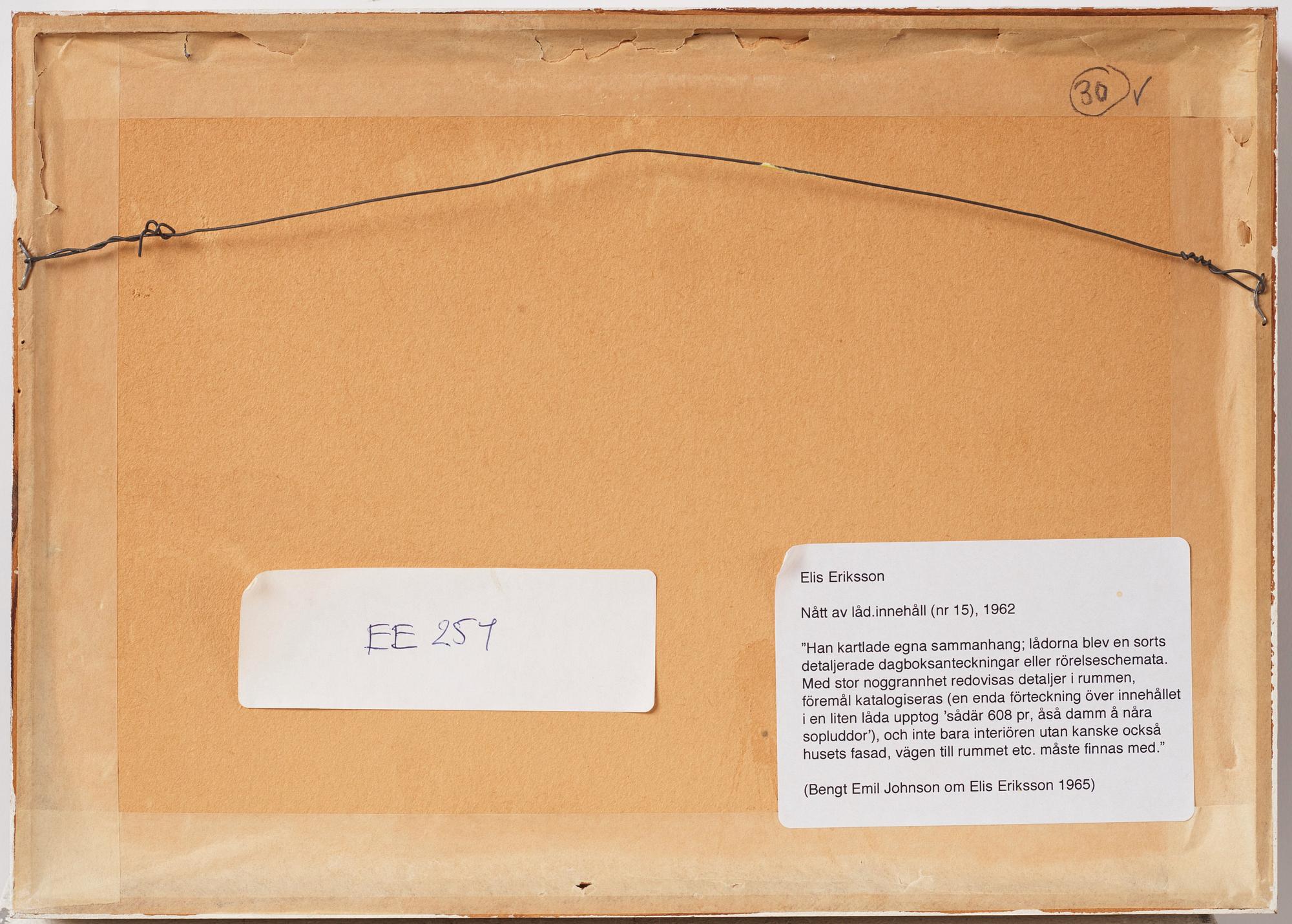

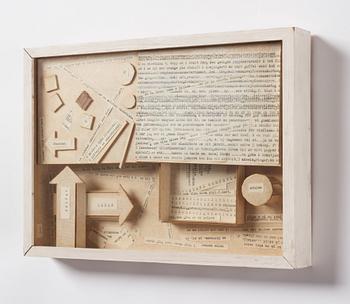

Elis Eriksson

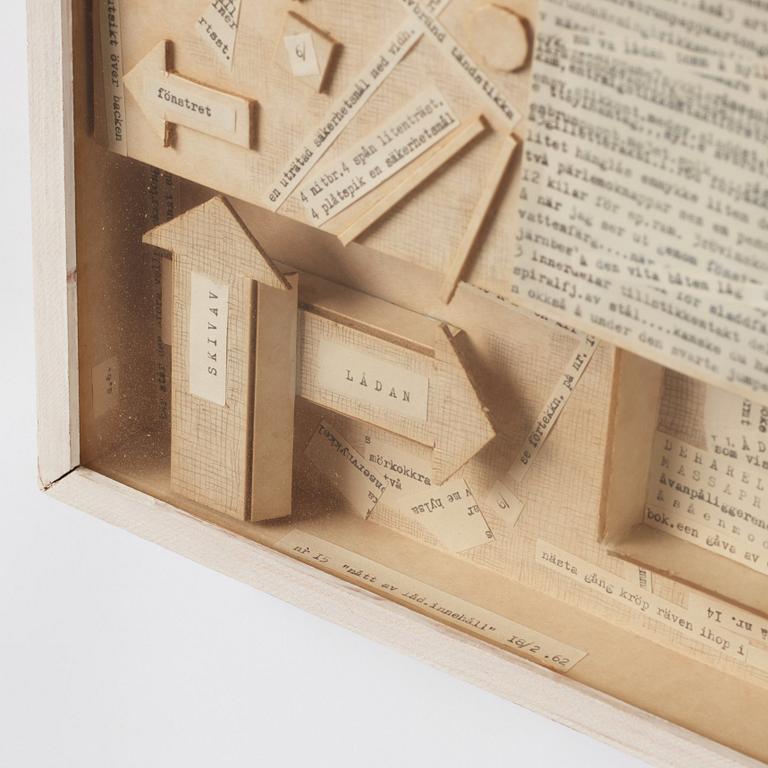

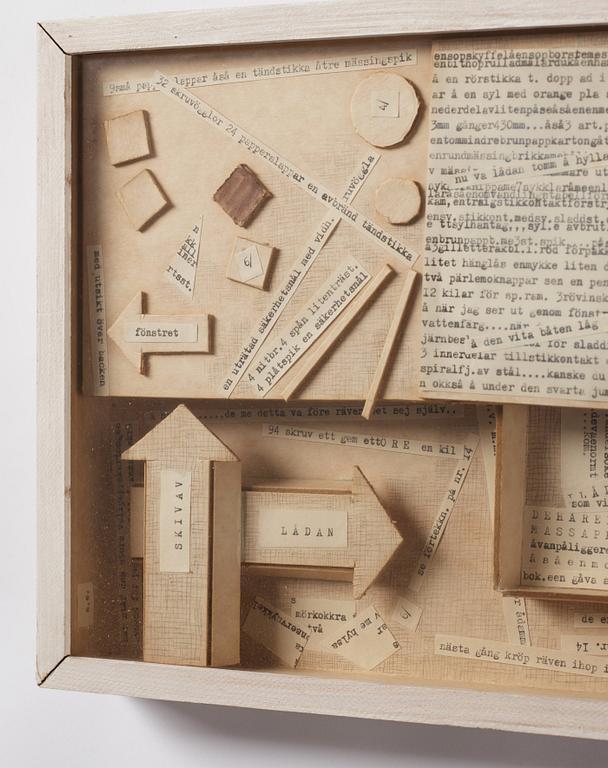

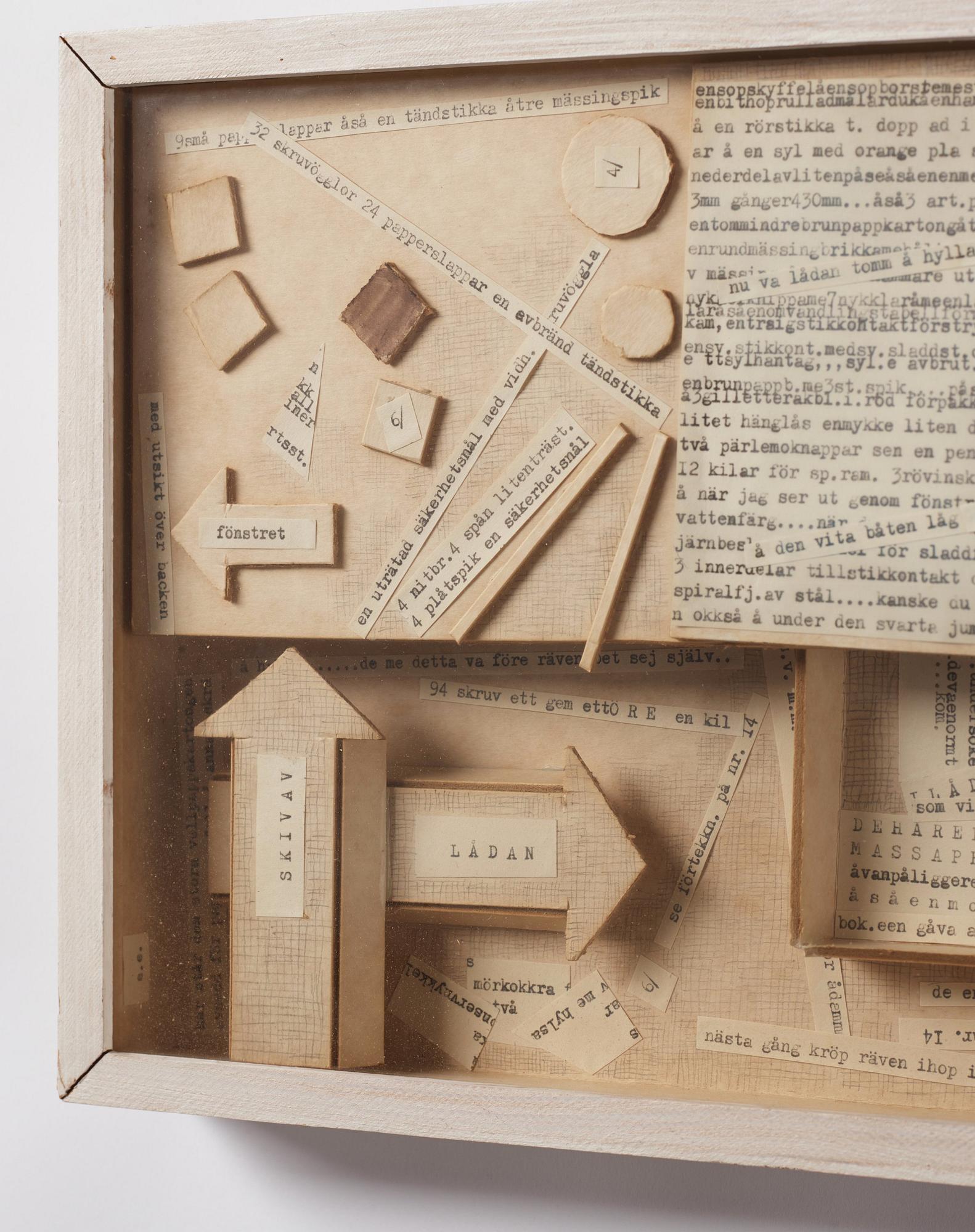

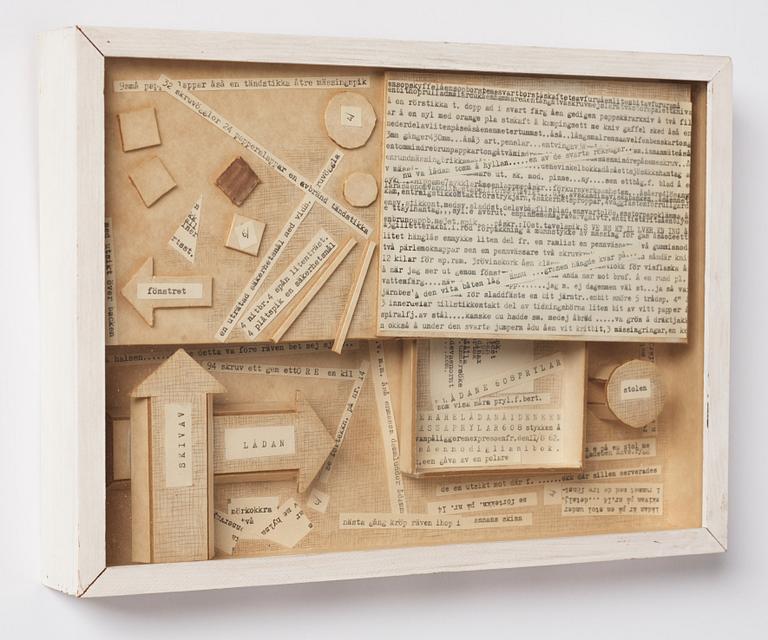

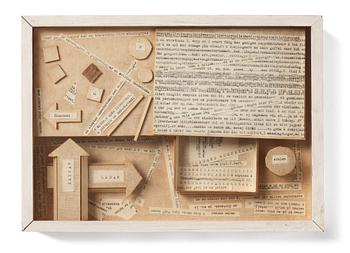

"Nått av låd. innehåll (nr. 15)"

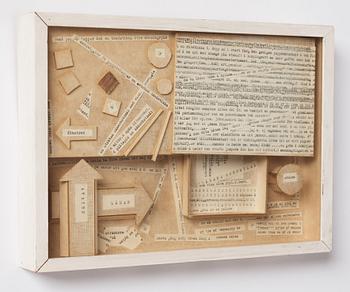

Signed e.e. Executed in 1962. Collage and mixed media in wooden box 21.5 x 30 x 4 cm.

Exhibitions

Galleri Burén, Stockholm, "5 kronor och 6 öre", 1963.

Literature

Teddy Hultberg, elis ernst eriksson - "100 år av åtlydnader", Schultz förlag, 2006, illustrated full page p. 205, listed in the list of works with no 118.

More information

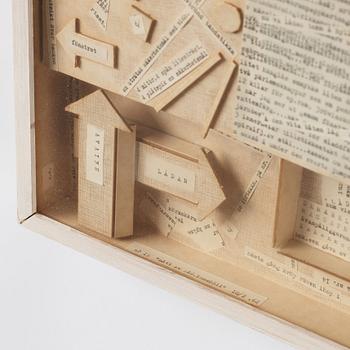

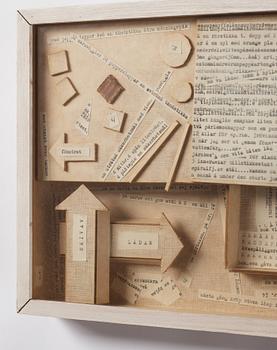

The auction's work, ‘nått av låd, innehåll (nr 15)’ from 1962, is part of the series of 30 ‘boxes’ with collage and typewriting from the exhibition ‘5 kronor å sex öre’ at Galerie Burén in 1963. The series is an intricate diary, a camouflaged documentation of a private sequence of events, involving the break-up of a thirty-year marriage and the birth of a daughter in a new and short-lived relationship.

The details and room plans of three different apartments in Stockholm are described in great detail. Arrows mark movements within the rooms and between the home and the studio at Döbelnsgatan 63, Gottes' studio, which he borrowed from Bertil Gottsén, at Bastugatan 12B and Rosengatan 1, where the artist with whom Eriksson socialised lived. Cut-out strips of typewritten text form a poetic carpet of thoughts and snippets of conversations that were held. Some words are coded and interspersed in the texts. The orange that is often mentioned is the growing foetus. The fox that appears several times in the work in question is a special fox boa with a buckle. The fact that all the boxes in the series form a whole is confirmed by references to other boxes in the works. For example, ‘see front cover of no. 14’ and ‘the box is on a chair under the disc of no.14 ...detail.’

The peculiar way of writing is one of the most distinctive features of Eriksson's oeuvre. It is a language game, in which words are axed, spelt as they sound and stacked like dominoes one after the other. The artist himself never wanted to describe this language as elaborate, but claimed that the expression came to him during his work.

At this time in the early 1960s, avant-garde and experimental poetry was flowing, both delighting and upsetting its readers. Eriksson was one of the participants in the artist group Svisch, which travelled around the country performing literary happenings and holding exhibitions of concrete poetry. The group also included Öyvind Fahlström, Bengt Emil Johnson and Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd. In concrete poetry, in addition to their semantic meaning, words also have a role as components in a visual experience. Words and sentences are taken apart and strewn across the pages in artistic figurations. The typewriter is used extensively, and edits and overwrites result in impenetrable carpets of letters and words. Other poems were designed as pure image collages, some were theatre texts or acoustic experiences. The boundaries between genres and art forms were erased.

Jan Olov Ullén writes in an essay in the Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet ‘Poetry that combined seriousness with playfulness’ 2005-06-23:

‘But it was certainly a wonderful time, when Hans Alfredson and Tage Danielsson developed Svenska Ord, Lasse O'Månsson challenged with crazy programmes on the radio and Karl Erik Welin blew up a piano at Moderna museet. Framed by poets, who sometimes semaphored their texts, sometimes performed them in chorus.’

With the radical politicisation of the cultural climate that occurred in the mid-1960s, concrete poetry almost completely disappeared in Sweden. Elis Eriksson continued linking image and language in his art. In 1965 he started a new project, the story ‘Indijaner å en kåvboj’, a series of drawings that told the fantastic and funny story of the hero Pavan.