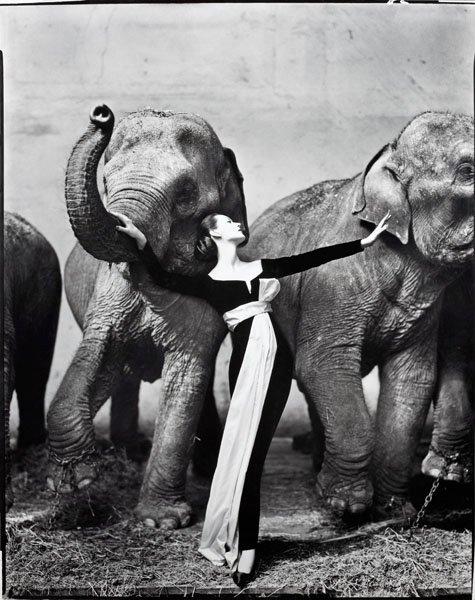

Richard Avedon

"Dovima with elephants, evening dress by Dior, Cirque d'Hiver, Paris, August 1955"

Signed Richard Avedon and numbered 13/50 on verso. Gelatin silver print 130 x 106 cm.

Provenance: Acquired directly from the photographer by current owner in the late 1970's.

Provenance

Acquired directly from the photographer by current owner in the late 1970's.

Literature

Harper's Bazaar, September 1955.

Harold Brodkey (e.a), "Avedon Photographs 1947-1977", 1978, reproduced fullpage pl 159 and on back cover.

Nancy Hall-Duncan, "The History of Fashion Photography", 1979, reproduced fullpage page 137.

Martin Harrison, "Appearances, Fashion Photography since 1945", 1991, reproduced fullpage page 73.

Adam Gopnik (e.a), "Evidence: 1944-1994", 1994, reproduced fullpage page 53.

James Danziger, "American Photographs 1900/2000", 2000, reproduced pl 129.

Anne Hollander (e.a),"Woman in the

mirror", 2005, reproduced fullpage page 37.

Michael Jensen (e.a), "Richard Avedon Photographs 1946-2004", 2007, reproduced.

Carol Squiers (e.a), "Avedon Fashion 1944-2000", 2009, reproduced fullpage page 137.

More information

A famous photograph

Richard Avedon is one of the few fashion photographers who broke loose from traditional studio photography and created something that revolutionised the genre. His style differed significantly in that he photographed in authentic settings, preferably outdoors, instead of in the studio, as was customary in fashion photography until the 1950s. Avedon was inspired by the Hungarian photographer Martin Munkacsi and began taking pictures of moving models with expressive gestures, rather than the static poses that were de rigueur at the time. He placed his models in settings ranging from street pavements to cafes and casinos.

In August 1955, Avedon chose a highly unusual place for an assignment for the French fashion house Christian Dior, namely the famous circus Cirque d'Hiver in the 11th arrondissement of Paris. Avedon was only 32, and had been a professional photographer for ten years, ever since he was recruited in 1945 for Harper's Bazaar by the influential art director Alexey Brodovitch. With his inventiveness, enthusiasm and sense of style, he soon became an influential name in fashion photography.

The photo shoot for “Dovima with elephants, evening gown by Dior, Cirque d’Hiver, Paris, August 1955” took place on a warm summer’s day, and Avedon has related how the first thing he saw on entering the building was the fantastic light falling on the animals:

“I saw the elephants under an enormous skylight and in a second I knew… there was the potential here for a kind of dream image.”

The tall, slim model Dorothy Virginia Margaret Juba, who went by her artist name Dovima, epitomises the elegant 1950s style and is said to have been the best-paid model of that period. Dovima and Avedon often worked together, and she frequently referred to herself and Avedon as Siamese twins, where Dovima knew exactly what Avedon wanted, long before he opened his mouth. In this picture, she is wearing an ankle-length black dress with a white sash from Dior, designed by Dior’s then 19-year-old assistant Yves Saint Laurent. Richard Avedon praised Dovima as the last of the great elegant and aristocratic beauties. He considered her to be the most remarkable beauty.

The picture has become legendary for several reasons; partly because of the fantastic light and the way it enhances the model’s spectacular pose. Dovima and the elephants is a veritably surrealist composition, both captivating and unexpected. The contrasting elements give the image a fascinating depth: young and old, strength and fragility, elegance and ungainliness, freedom and captivity. All this, in combination with the painterly qualities, make it far more than an ordinary fashion photo.

When the photo of Dovima was published in Harper’s Bazaar in September 1955, it was seen as ground-breaking. Avedon realised the potential of his image and had one of the larger prints on show in the foyer of his studio for more than 20 years. Both the photo and Avedon had brilliant careers ahead, but the fate of Dovima was not as illustrious. When she gave up modelling, she got a few minor parts in films but ended up working in a pizza parlour. She died in 1990, at the age of 62. Richard Avedon came to be one of America’s most appreciated, celebrated and influential photographers up to his death in 2004, and Dovima with Elephants is generally regarded as one of the most famous fashion pictures of the 20th century.

Richard Avedon

Avedon was granted the Hasselblad Award in 1991. By then, he already had an honorary doctorate from the Royal College of Art in London and the magazine Popular Photography had listed him as one of the world’s ten best photographers, to name but a few of his distinctions.

To understand Avedon’s fantastic career it is necessary to go back to his childhood in New York. His family came to the USA as immigrants; his father was of Russian Jewish heritage and was born on the journey over the Atlantic. His father had done well and had a successful clothes shop on the fashionable Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Thus, Avedon grew up in his father’s shop, surrounded by the glossy magazines such as Harper's Bazaar, Vogue and Vanity Fair. Avedon was inspired by the fashion pictures and started photographing his own family posing in front of other people’s houses and luxury cars, often with borrowed dogs. “All of the photographs in our family album were built on some kind of lie about who we were, and revealed a truth about who we wanted to be." Avedon realised at an early stage that he could “create” pictures and not just “take” them, and this sums up his photographic approach. A style that resembles that of a film director rather than a photojournalist. In the same way that he created family pictures in his childhood, mixing one part truth with one part longing and a large portion of imagination, he borrowed material from reality and staged his own scenes.

As mentioned, Avedon’s talent was discovered in 1945 by the legendary art director Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar. The good fortune of having Brodovitch as a benefactor was shared by Irving Penn and Robert Frank. Avedon began taking photos for Harper’s Bazaar and also started at Brodovitch’s groundbreaking “Design Laboratory". Together with Irving Penn, Avedon dominated American fashion photography from the late 1940s. Both survived in a profession where fashions, people, styles, taste and trends are constantly changing.

Over the years, fashion assignments became a way for Avedon to finance other activities.

In 1948, he was employed as a photographer and editor of “Theatre Arts”, for which he took many seminal theatre portraits. These powerful portraits were taken in a flat lighting against a grey or white background. The results are reproduced in the books “Observations” (1959) and “Nothing Personal” (1964).

Avedon continued to work for Harper’s Bazaar until 1965. In those years, he took many controversial photos that stirred up the fashion scene. He was the first, for instance, to use black models, the first to get pictures of famous women in the nude published in a fashion magazine, and the first to shoot bikini pictures, which was considered to be extremely daring in the USA at that time.

In the global student revolts of the 1960s, Avedon investigated the American power structures. He portrayed political representatives and, during a seven-week journey in Vietnam in 1971, photographed the rank and file of the US forces. In 1976, the USA celebrated its Bicentennial, and Avedon filled an entire edition of Rolling Stone with his 69 portraits of the political power spectrum, people like union leaders, leading journalists and heads of corporations and state. Another acclaimed series of photographs comprised eight gigantic pictures that shocked New Yorkers at the MoMA in 1974. The exhibition featured pictures of his father, who was dying of cancer. The commotion was matched the following year, when Avedon was the first photographer to be exhibited at the Marlborough Gallery, a prestigious art gallery on 57th Street in New York, where he showed portraits of famous artists, writers, musicians and politicians. The exhibition was a roaring triumph with both critics and the public. Avedon’s success and acclaimed exhibitions of photographers such as Irving Penn established photography as a collectible and turned photography into a viable investment object. That year, in 1975, Sotheby's and Christie’s held their first photography auctions.

The Amon Carter Museum in Texas invited Avedon in 1979 to portray the American West in the form of an exhibition. The concept of the West is more than just a geographical region of the American Midwest. It is a culture and a lifestyle that has been immortalised by artists like Georgia O’Keefe, photographers like Edward S. Curtis and Ansel Adams and actors including John Ford and John Houston. In Avedon’s pictures of the Wild West he leaves out the Rocky Mountains and Grand Canyon and focuses exclusively on people. During six summers, in 1979-1984, Avedon travelled around with a large-format camera and a mobile studio, documenting local meeting places like folk music festivals and rodeos. After a while, Avedon decided to photograph 754 of the many, many people he met. He finally selected 123 whom he worked on more intensively. He positioned his models at arm’s length from the camera, and the chemistry and social interplay that arose between them determined the outcome of the portrait. Commenting on his portraits, Avedon once said: “The moment an emotion or a fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. My portraits are opinions and my opinions are strong."