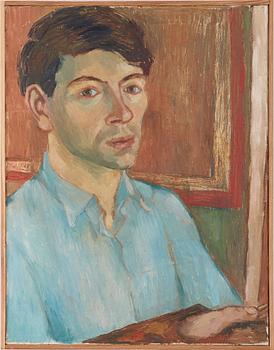

Peter Weiss – artist, filmmaker and author

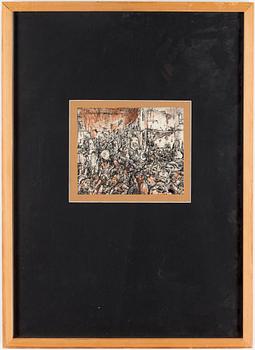

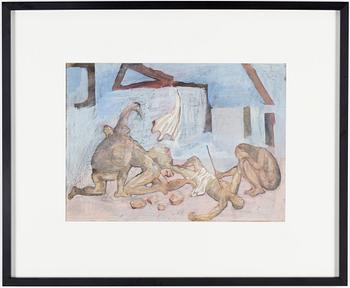

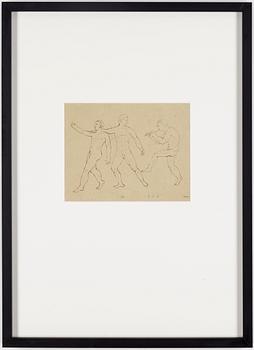

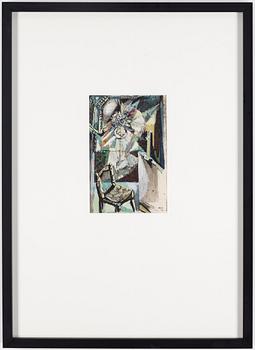

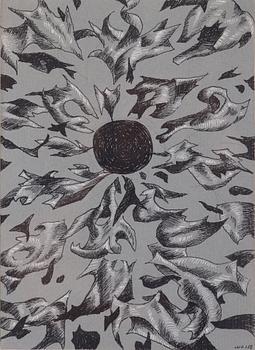

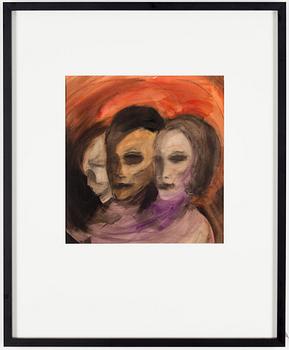

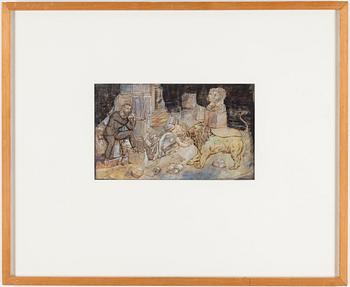

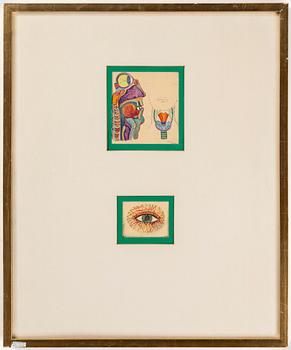

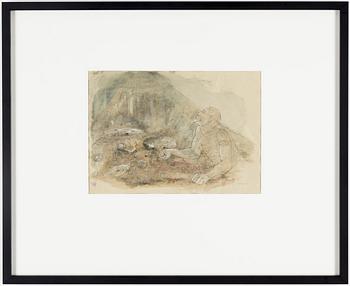

Peter Weiss, ”Fahrende Schauspieler” (detail). See the artwork here >

Viewing: January 23 –26 at Berzelii Park 1 in Stockholm. Open: Mon–Fri 11–18, Sat 11–16

Online auction: January 12–28

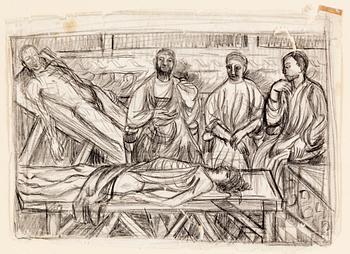

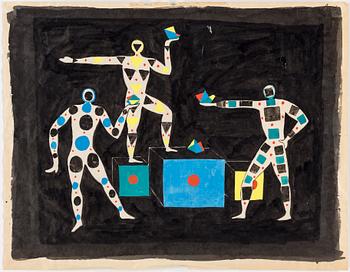

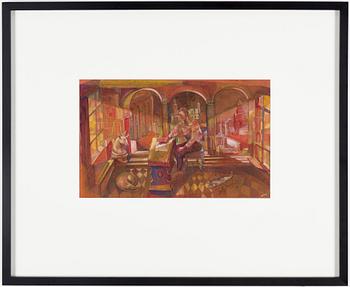

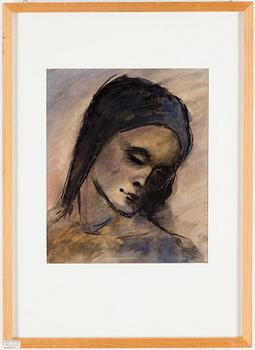

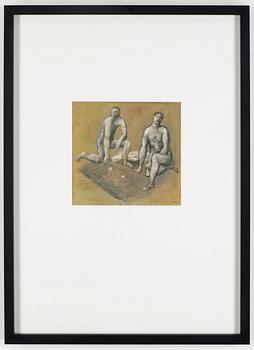

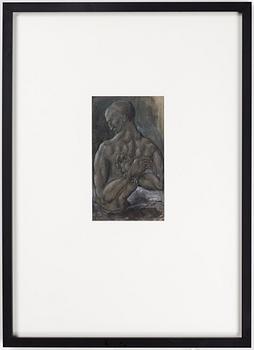

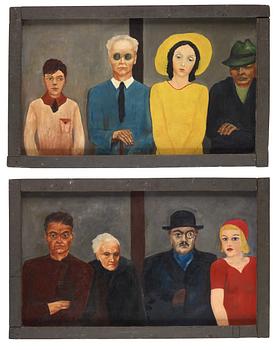

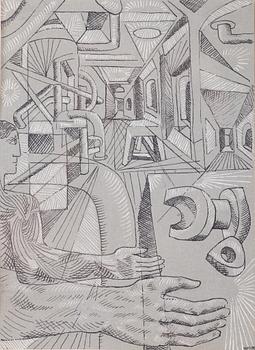

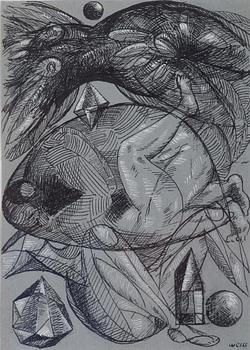

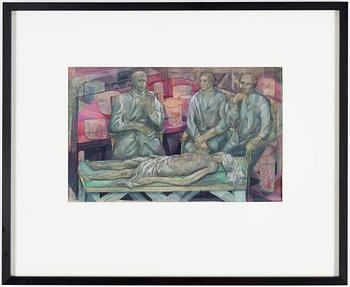

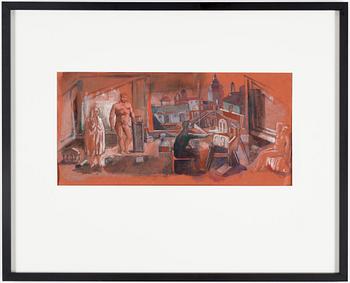

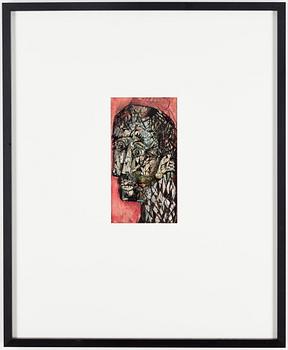

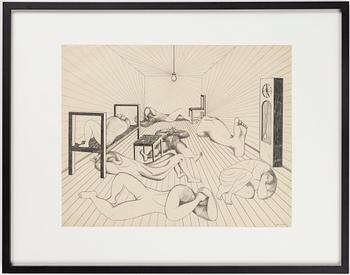

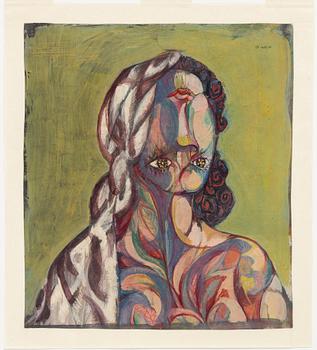

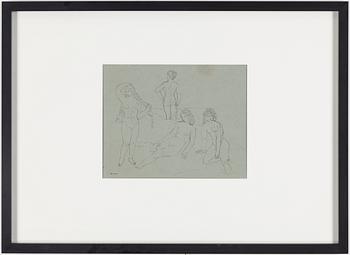

Peter Weiss’ painting was influenced by old masters such as Bosch and Brueghel and by contemporary Surrealists such as Max Ernst and Man Ray. Bukowskis has been entrusted with auctioning a collection of almost 50 works of art, from his earliest oil paintings in the mid-1930s to the late 1950s. Ahead of the auction, we talked to Peter Weiss’ wife, Gunilla Palmstierna Weiss.

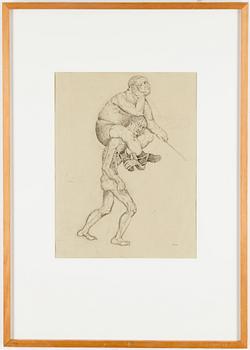

Peter Weiss trained in the 1930s in Berlin, Bremen, London, and in Prague, where Surrealism and Dadaism were flourishing, while also being influenced by Renaissance artists such as Bosch and Brueghel. What was it about these disparate styles that attracted him?

Peter was predominantly interested in Bosch and the symbolism of Surrealism. He also wanted to get back to the fundamentals of painting, learning to master the techniques of the past. His artistic training was founded in a Central European tradition, as it was for his friend and colleague Endre Nemes.

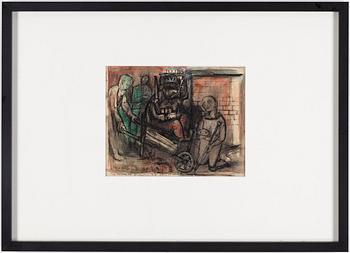

Even when Peter Weiss painted People in a tram I and II, one of his earliest works, he was writing texts in parallel (including Günter an Beatrice, Traum and Dämmerung). What attracted him most, painting or writing?

Both, right from the start. When Peter was living in London in the mid-1930s, he corresponded with the Swiss writer Herman Hesse, who commissioned him to illustrate some of his short stories. Hesse considered that Peter had more talent as an artist than he did as a writer. It was Hesse’s contacts with the Prague Art Academy that saw Peter accepted there in 1937. Hesse’s encouragement meant that painting took precedence at this point but even then, he was a literary artist and an artistic author.

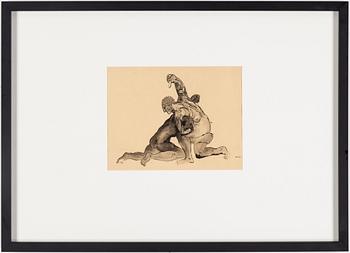

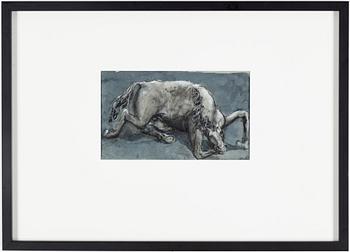

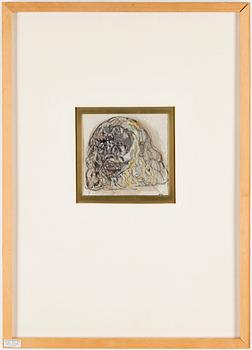

Peter Weiss often returned to different themes in his paintings; self-portraits, lions and deserted places. What did this symbolise?

The lion symbolises strength and loneliness. The self-portraits are fairly self-explanatory. Whether the paintings are deserted places or depict crowds of people, he often put himself in there in a corner. The subjects are clear contemporary depictions of human vulnerability in different situations in a general sense, without necessarily being political. He only became politically active later on in the mid 1960s when we were mostly concerned with Vietnam and the attacks on the Left going on in Germany at the time. The plays Marat/Sade and The Investigation came out of his views on those issues.

The book The Aesthetics of Resistance was published in the mid-1970s. Here Peter Weiss addresses a view of art that incorporates reproductions set against the original, ideas that are central to much of Postmodernist art.

Peter was very interested in examining his own time in relation to history. He actually intended it to be a much shorter book but in the end The Aesthetics of Resistance filled three volumes and took nine years to write. It was a work in which he succeeded in combining painting, literature and music (when the text is read aloud it has a clear musical rhythm). In principle, he stopped painting after completing the illustrations to A Thousand and One Nights in the late 1950s. After The Aesthetics of Resistance, he took up the collage technique again but he sadly died soon afterwards, at the age of only 65.

When we read bibliographies of Peter Weiss’ works, they mainly list plays, books and films. The first time his painting attracted attention was in an exhibition at Södertälje Art Gallery in 1976. Why was that?

It was Per Drougge, the manager of the art gallery, who wanted to hold an exhibition that focused on Peter’s painting. The exhibition then toured other European cities and played a part in raising the profile of his work as an artist. It was a powerful experience for Peter to see so many of his works gathered together in an exhibition after all those years.

In spring 2008, several hundred works by Peter Weiss were stolen and most of them have never been recovered. The catalogue for the Peter Weiss exhibition at Uppsala Art Museum in 2016 stated that: “With a kind of historic irony, [the theft] thus completed the erasure of Weiss’ pictorial art that began a long time ago.” What do you think about that sentence?

I see it the other way around. Peter constantly expressed himself in pictures. When he stopped painting, he made a number of films before then moving to text. His entire life was the ongoing experiment of a painter. It simply moved through different forms of expression.

Contact: