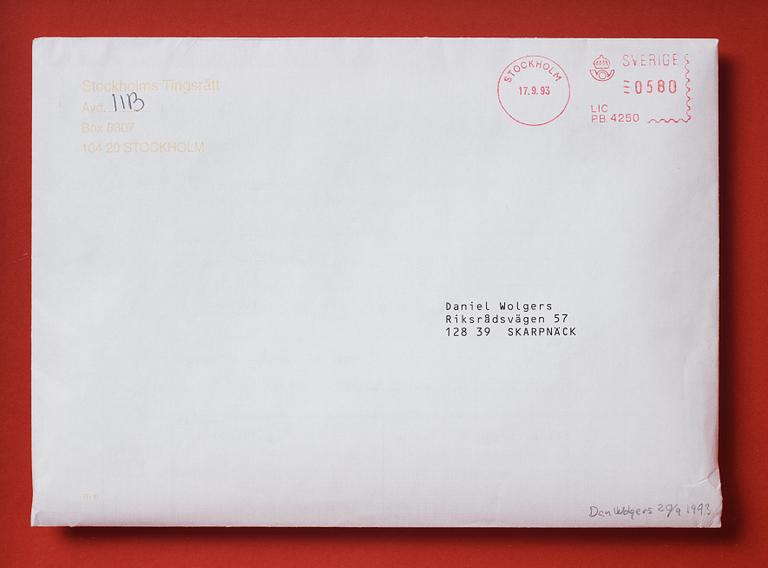

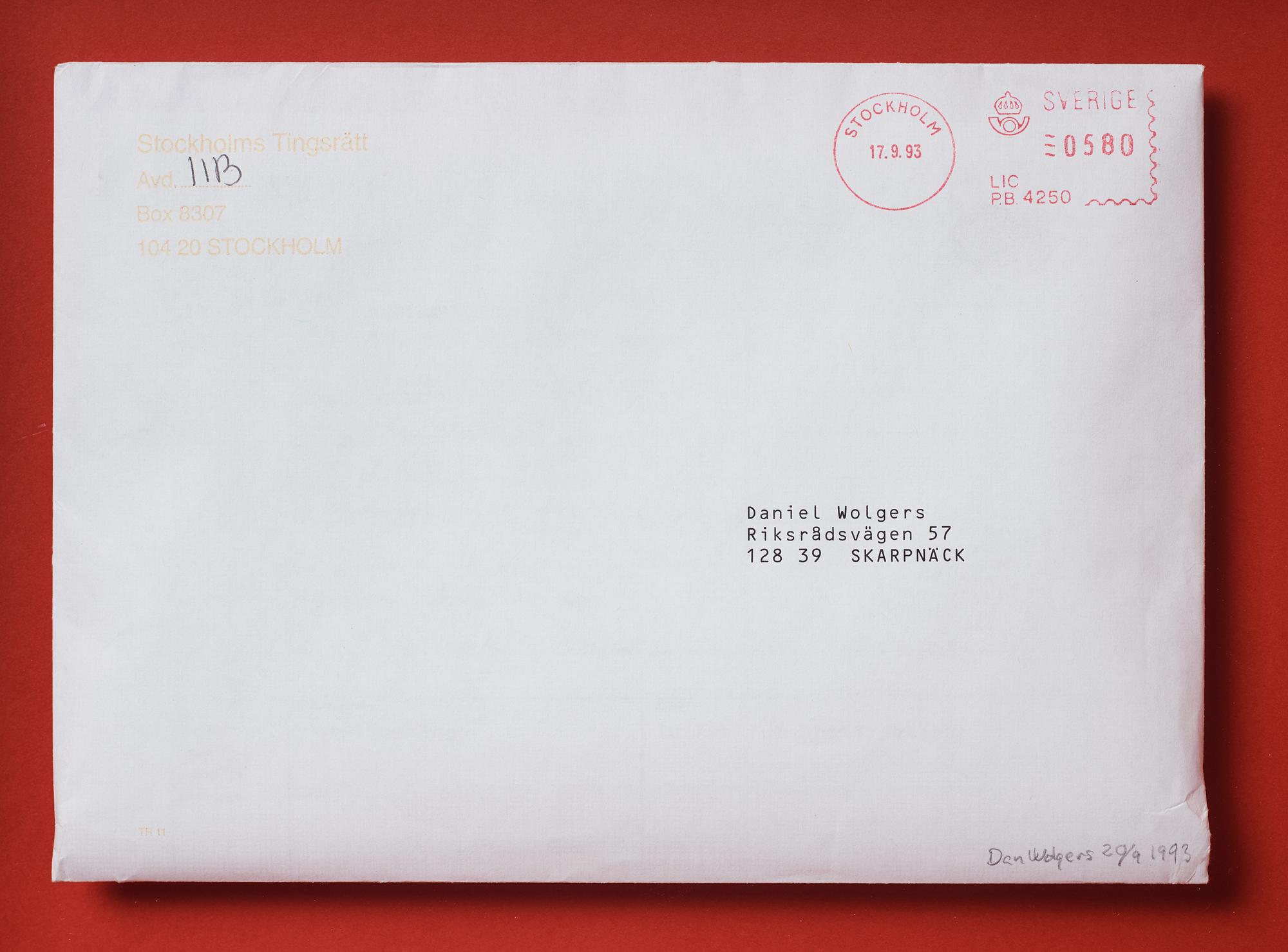

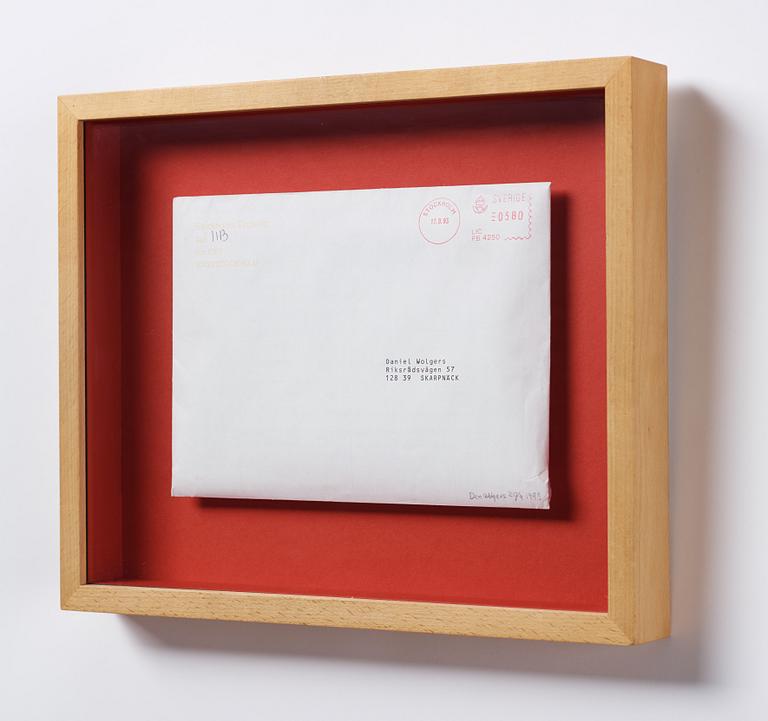

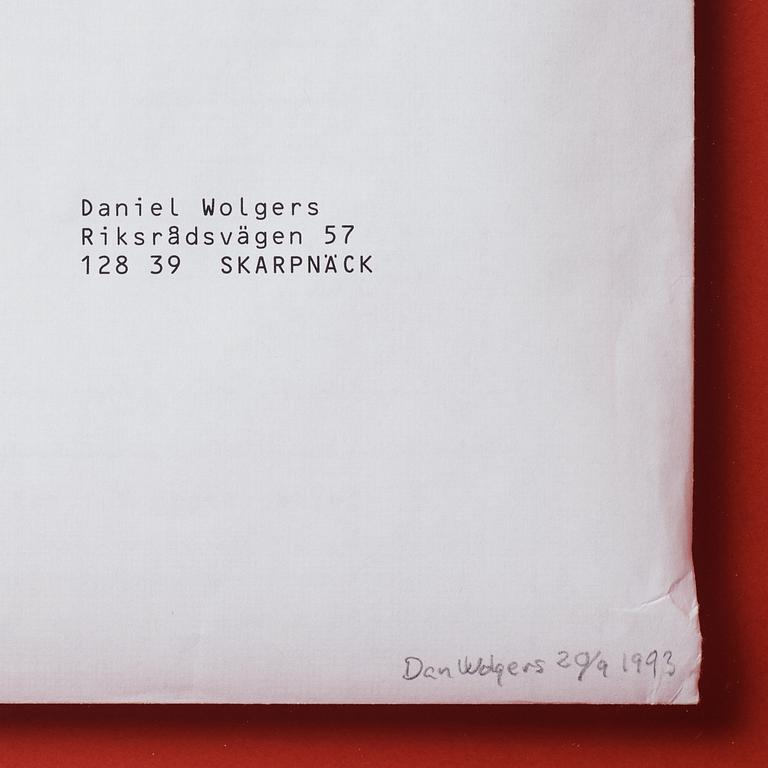

Dan Wolgers

"Domen"

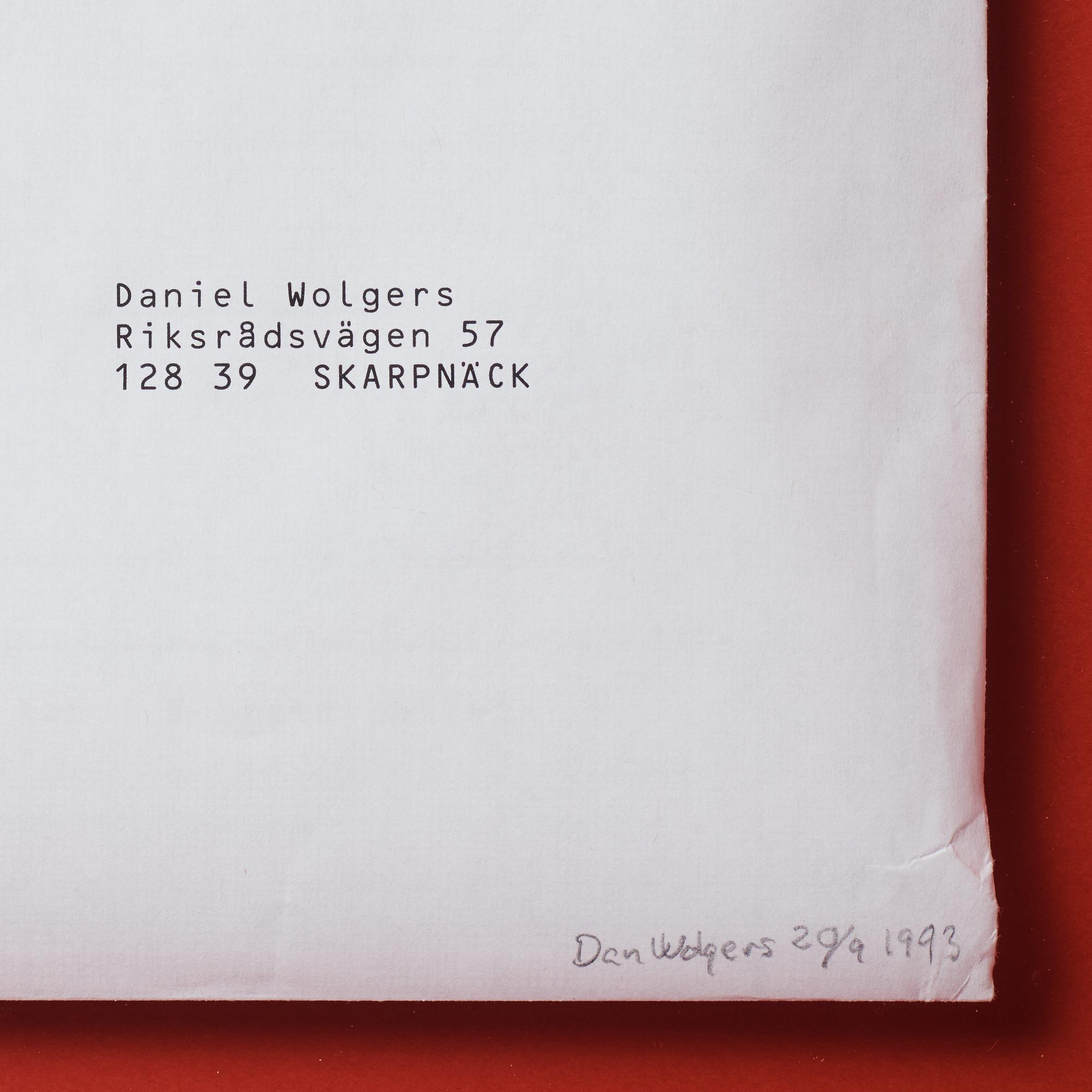

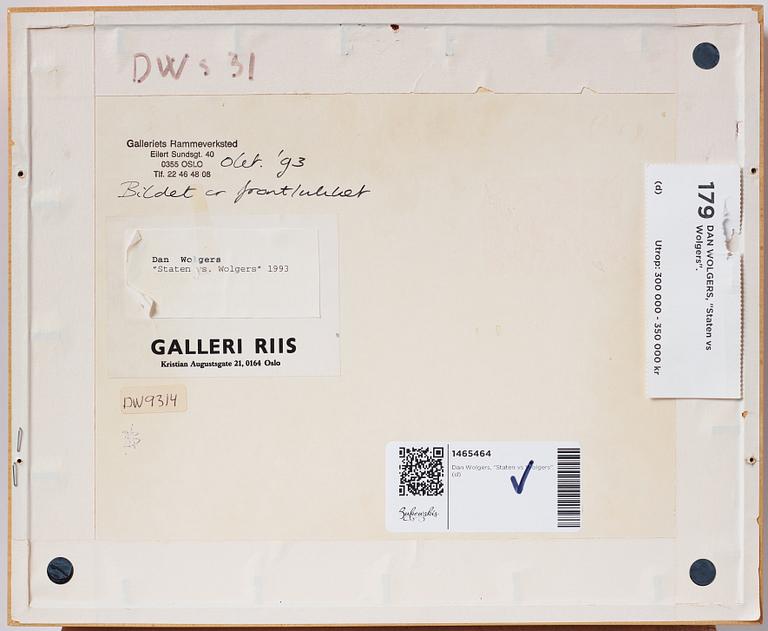

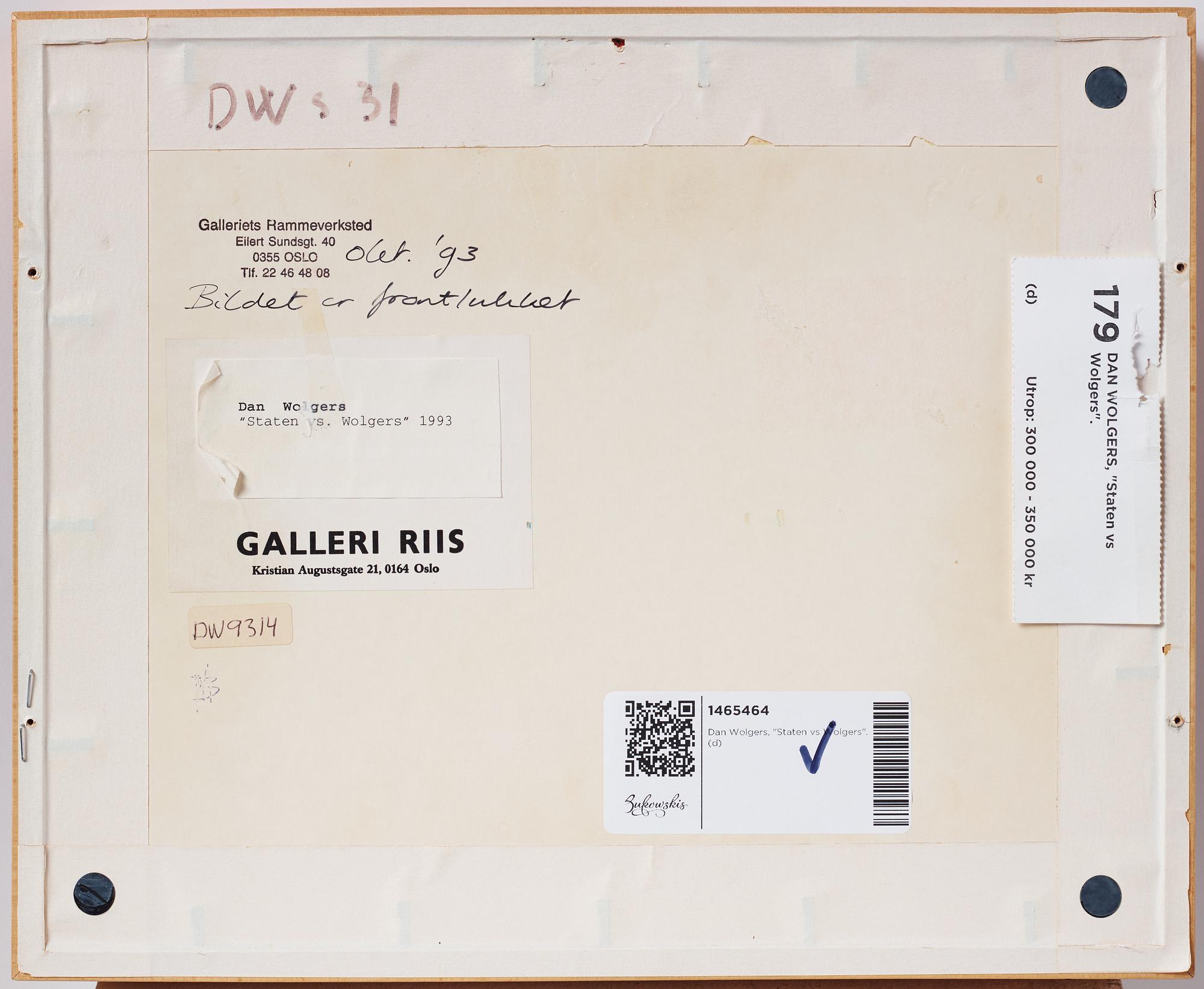

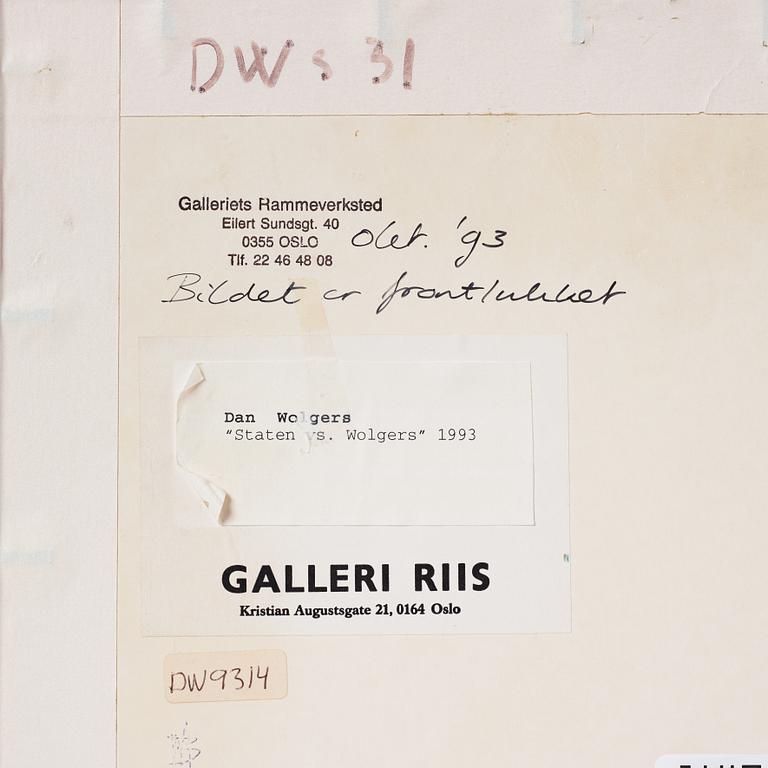

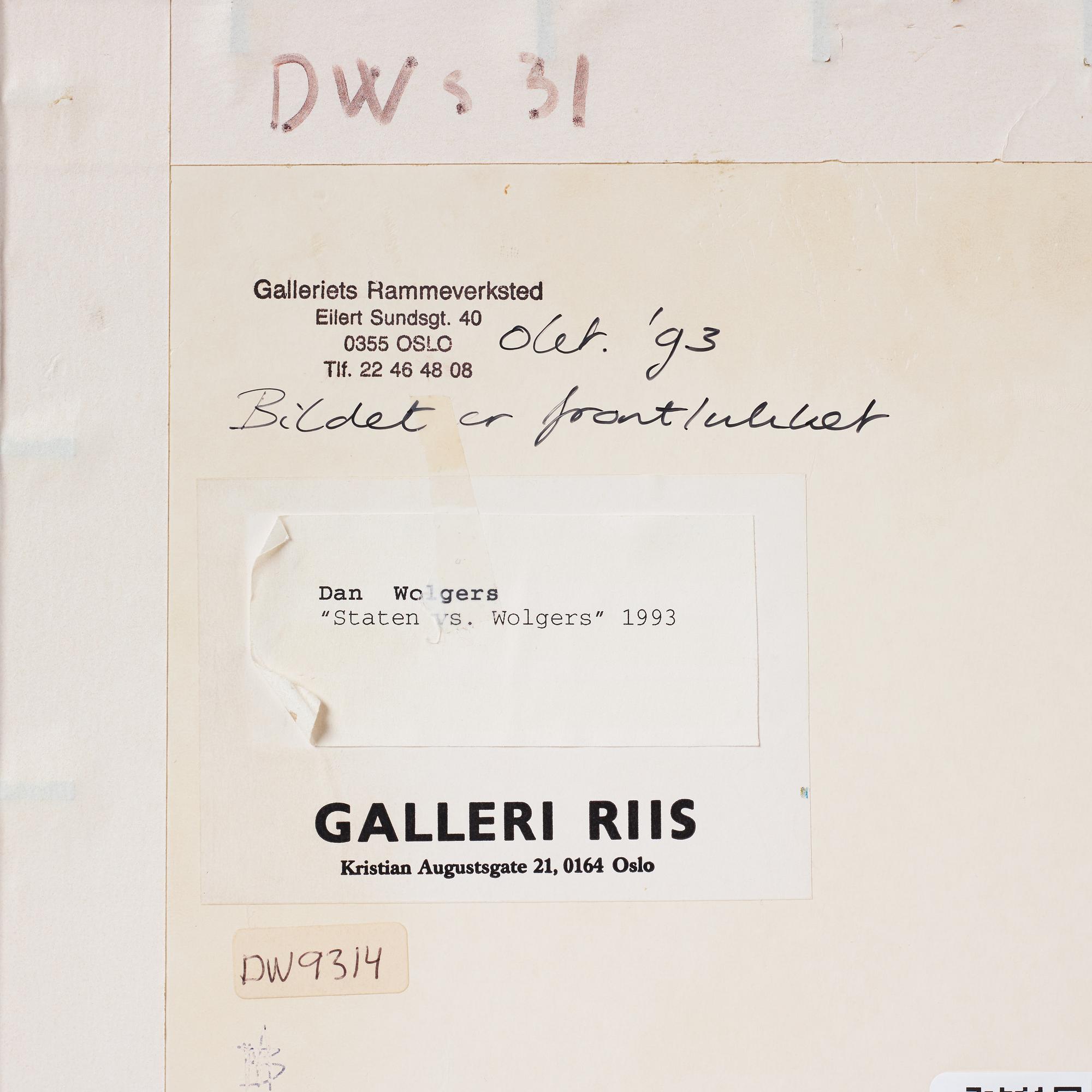

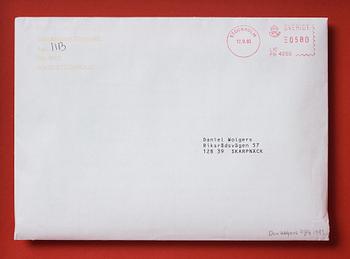

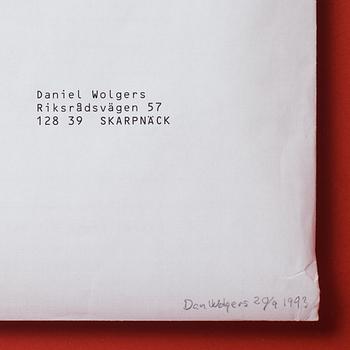

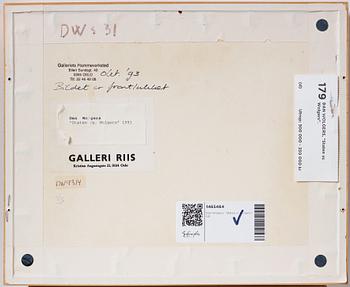

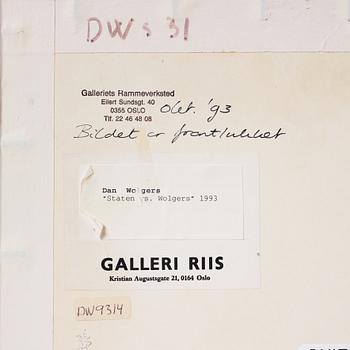

Signed Dan Wolgers and dated 20/9 1993. A letter mounted in frame 28 x 34 cm.

Provenance

Galleri Riis, Oslo.

Stockholms Auktionsverk, 2007.

Private Collection, Stockholm.

Bukowskis, Vårens Contemporary 2016, Stockholm 592, cat. no. 179.

Tom Böttiger Collection, Stockholm.

Exhibitions

Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm, "Dan Wolgers", 27 October - 6 January 2002.

Malmö Konstmuseum, "Dan Wolgers", 10 February - 7 April 2002.

Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm "Jubileumsutställning", 15 October 2021 - 16 January 2022.

CF Hill, Stockholm, "Samling Tom Böttiger, Part I", 26 September - 15 November 2019.

Literature

Dan Wolgers and Pontus Hultén, "120 verk 1977-1996", 1996, illustrated on fullpage p. 102.

Dan Wolgers e.a, "Dan Wolgers, Verksamhet 1977-2001", 2001, Liljevalchs Konsthall cat. No. 453, illustrated on spread.

Exhibition catalogue, Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm "Jubileumsutställning", 15 October 2021 - 16 January 2022, ill in colours under year 1992.

More information

The Verdict is one of Dan Wolgers' most renowned art pieces, and it secured its place in Swedish art history the moment it was signed. However, it was simultaneously torn from its actual context and taken into its own realm, where myth and reality have gradually intertwined. Here, Dan Wolgers has compiled the background of this legendary ready-made in his own words for the first time:

In the spring of 1992, Liljevalchs Art Hall invited around twenty Swedish artists to participate in a group exhibition that was scheduled to open in November of the same year. The exhibition was named "Se människan," which translates to "See the human being" and refers to Pontius Pilate's exclamation when he presented the scourged Jesus to the roaring crowd shortly before the crucifixion. It is tempting to understand the title as the art hall considering its art to be sacred and exhibiting it to an uncomprehending audience.

For the exhibition's vernissage, an exhibition catalog was to be compiled with a simple presentation of the participating artists. I accepted the invitation, well aware of the conditions that prevailed at the time regarding exhibition compensation. The concept of exhibition compensation did not yet exist (it wasn't until 2009 when the so-called MU agreement was signed between the state and several artistic organizations). In 1992, and probably still in practice today, artists individually negotiated with the commissioners (in this case, Liljevalchs Art Hall) and competed with each other for compensation until the commissioner's meager exhibition budget was depleted. Those who were granted funding may have received a few thousand Swedish kronor, but in general, the commissioner claimed that it was sufficient compensation for the artist to have the opportunity to exhibit their work free of charge. In practice, it was the artist, at the bottom of the food chain, who financed the art hall's mission to showcase art for the public with their own money and labor.

This time, I decided not to embarrass myself or the exhibition commissioner with negotiations about money that would be humiliating for both parties.

In the art hall, there were, and still are, a dozen or so benches in the exhibition rooms for visitors to sit on. I informed the exhibition commissioner that I needed two of the benches for my participation and, without any questions or objections, he helped me carry the two benches to my car outside the main entrance. In my studio, I tidied up the benches, removed the labels on the inside of the frame, and scraped off hidden chewing gum (which is now in the collection of the Moderna Museet, the labels, that is). After that, I transported the benches to a photo studio for the image in the exhibition catalog and then directly to submission and display at Stockholms Auktionsverk, which was located in the center of Stockholm at the time. The timing of the submission was synchronized with the vernissage so that the auction would take place before, but as close as possible to the vernissage day, which happened to be only a few days apart. It was crucial for me that even though I hadn't fully disclosed what I intended to do for the exhibition (because what artist does?), the sale of the benches would still be conducted as openly as possible, and what is more open than a city auction in the middle of town? As the day of the auction approached, I received a phone call from the exhibition commissioner, who urged me to call back with a concerned and serious voice. I assumed that someone in the art hall's management had accidentally seen the benches at the exhibition and, to buy time, had refrained from calling me back. Finally, after repeated reminders, I found it unsportsmanlike to further delay the call and called back. I was then informed that the art hall had plagiarized my telephone directory cover for the exhibition catalog's cover, which was present in every home and workplace that year. The art hall had simply replaced all the information with their own. But now they had become remorseful and concerned about what they had done, now that the finished catalog had finally been printed and delivered to the art hall. I burst out laughing, and when asked what was so funny about the news, I replied, "Well, you'll see!"

It was only when the exhibition was fully hung the day before the vernissage, the benches were sold, and my empty space in one of the rooms still stood empty, that I told the management that my contribution to the exhibition was that by selling the benches at auction, I had arranged compensation for my work, and I had nothing more to contribute except for the sign on the wall that marked my empty space, even though the sign was put up by the art hall and not by myself (the sign was stolen a few days later). The management reacted with delight to my contribution and treated me to both lunch and dinners to discuss the matter further, as it had spread to the