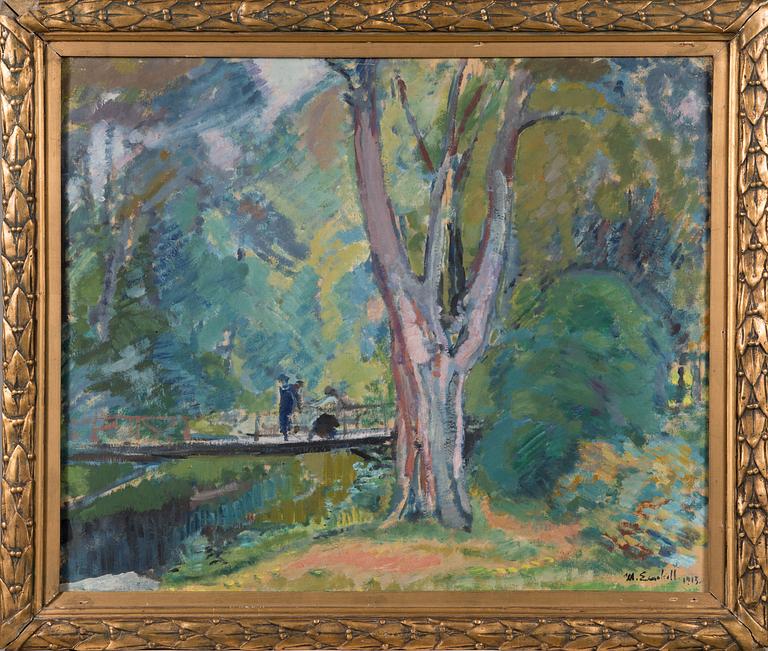

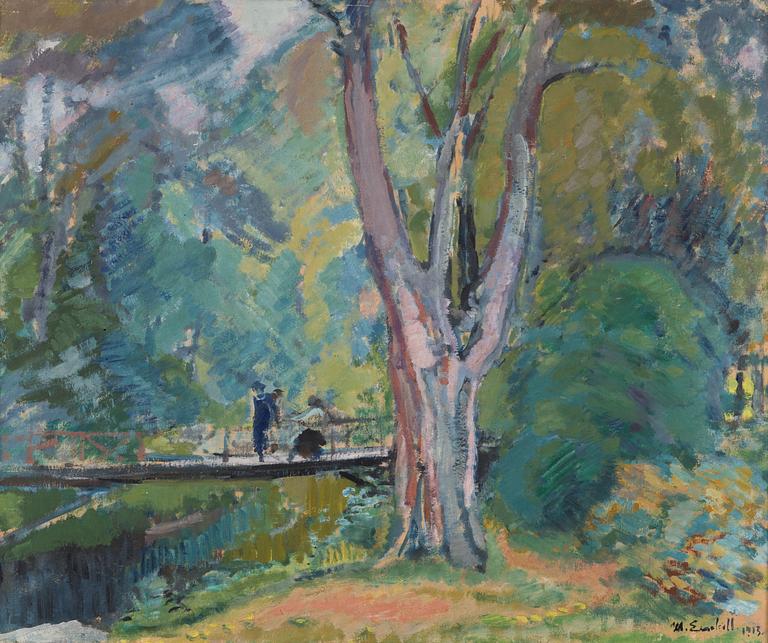

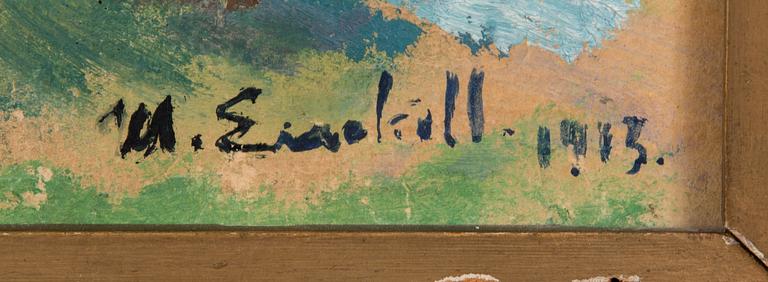

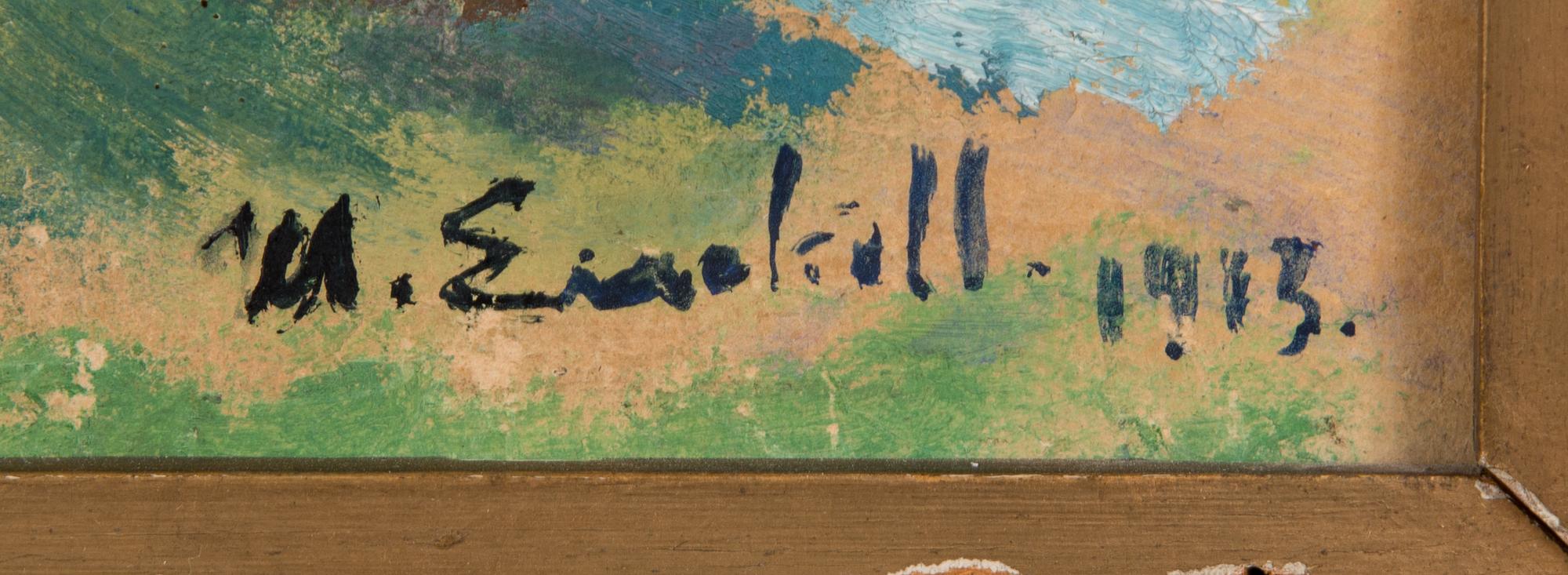

Magnus Enckell

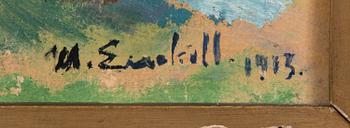

Magnus Enckell, View from Vääksy park.

Sign. 1913. Oil on panel 54x65 cm.

Wear due to age and use.

Literature

Jaakko Puokka, "Magnus Enckell- Ihminen ja taiteilija", Otava 1949, no. 324.

More information

Magnus Enckell (1870-1925) grew up in Hamina, in the Kymenlaakso province. He was the youngest of six to his parents, a docent of Greek and vicar Carl Wilhelm Enckell and his second wife, Alexandra Fredrika Appelberg. Carl Wilhelm didn’t think Hamina would offer appropriate school education for his youngest son, so in 1881 Magnus was enrolled at the Borgå Lyceum in Porvoo. Magnus was a withdrawn child, and only at Borgå Lyceum he made his first proper friend, Yrjö Hirn, who had a great influence on him. Hirn became later known as an aesthete and a literature scholar.

Magnus Enckell was interested in drawing from an early age on, but it was the cultured atmosphere of Porvoo and especially the acquaintance with Albert Edelfelt that led him to his path. Edelfelt recognised Enckell’s talent at an early stage and did his best to support and encourage him.

After his matriculation exam in 1889, Enckell moved to Helsinki to start his studies at the Finnish Art Society drawing school. The tuition, led by Carl Jahn, of German descent, and Fredrik Ahlstedt, was very routinelike and, only after a couple of weeks, Enckell expressed his discontent in a letter to his mother: “the tuition at the Art Societys drawing school is so terribly, so utterly awful that the only thing that can happen to me there is going backwards in my artistic development.” Enckell’s complaint resonated in some of his artist friends, for example in Väinö Blomstedt, Helmi Biese and Beda Stjernschantz, and they turned to Gunnar Berndtson, who promised to arrange them private tuition according to “the French method”. During that time, Enckell’s paintings were characterised by soft and somewhat romanticised realism.

Encouraged by Edelfelt, Enckell travelled to Paris in 1891 and started his studies in Académie Julian. He was strongly influenced by the French symbolists and neoplatonists, such as the mystic and author Joséphin Péladan. At first, he joined the Finnish artist colony but didn’t feel at home in it. After his return to Finland in 1892 he finished his first paintings with a boy motif: “Nude Boy”, “Two Boys” and “Resting Boy”. During his second period in Paris (1893–1894) he finished his works “Head” and “The Awakening”. The latter, depicting a waking youth, is probably Magnus Enckell’s most famous painting.

During his early career, Enckell’s reviews were often sour, or like in the case on “Melancholy”, downright depressing. This continued until the 1910s, when the public’s view in symbolistic paintings of the 1890s changed radically.

Enckell’s most meaningful project was organising Finland’s 1908 participation in the Salon d’Automne in Paris, and he managed to get Finland a section of its own. The mixed reviews for the exhibition in Paris were one of the reasons for Enckell to further develop his style. Pure colours and contrasts created by them became the leading principles in his art, and he was heavily influenced by his contemporaries Pierre Bonnard and Éduard Vuillard. He never gave up the motifs from the classical mythology, however, and the confrontation between apollonian and dionysiac art was a continuous source of inspiration and fascination for him. At the beginning of the 20th century, Enckell got acquainted with architect Sigurd Frosterus, who became an important atelier critic and a friend to him. Frosterus influenced Enckell to set himself to the path of Neo-Impressionism and encouraged him to gather other artists with a similar perception of art and to form an art group. Together with colleagues A.W. Finch, Verner Thomé, Mikko Oinonen, Juho Rissanen, Yrjö Ollila and Ellen Thesleff, Finland’s first real art group Septem was formed, and their first joint exhibition in 1912 is considered to be the breakthrough of modern art in Finland. At first, the group enjoyed a positive reception, but later the more nationally focused November group, led by Tyko Sallinen, received more credit. Septem was considered much too academic and intellectual, even though the group had a massive influence on the use of colour by contemporary artists.

Enckell acted as the chairman of the Artists’ Association of Finland during 1915–1918 and always defended his impartial and liberal views of art. Belonging to the art world’s elite of his time, Enckell received a great number of public artwork commissions. Aforementioned Yrjö Hirn and Sigurd Frosterus, together with Torsten Stjernschantz, belonged to Enckell’s closest circuit and influenced his artist’s path and orientation throughout his career.

In Finnish art history, Magnus Enckell was long neglected because of his nude motifs. These paintings did not fit in the nationalistic writing of history, characterised by heterosexuality. Even though Enckell has always been portrayed as one of the masters of the Golden Age of Finnish Art, he has often been shoved to the margins due to his uncomfortable motifs. As an artist, he was also seen as not “genuinely Finnish” enough, and his individualism and disgust for mass movements burdened his success. Throughout his career Enckell was considered to be a difficult and intellectual artist.

Magnus Enckell was a true cosmopolite and always open for international trends, and his art reflected this in many ways. In his landscape paintings, Enckell made no distinction between domestic and foreign motifs but depicted them always in the same manner. When examining these two colourful landscape motifs in the Neo-Impressionist style now being auctioned, one can be surprised to learn that they are in fact purely Finnish views from Vääksy.