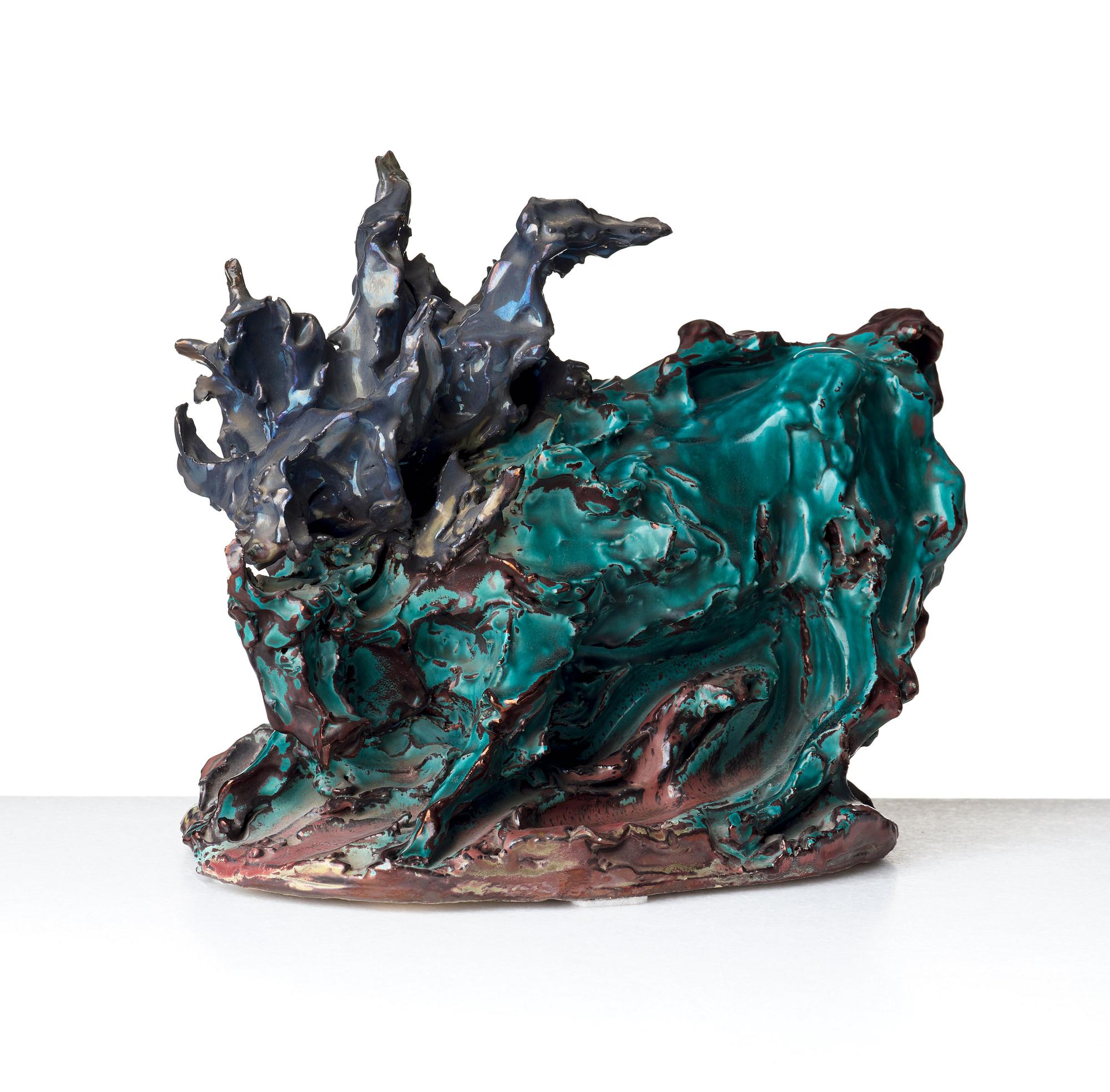

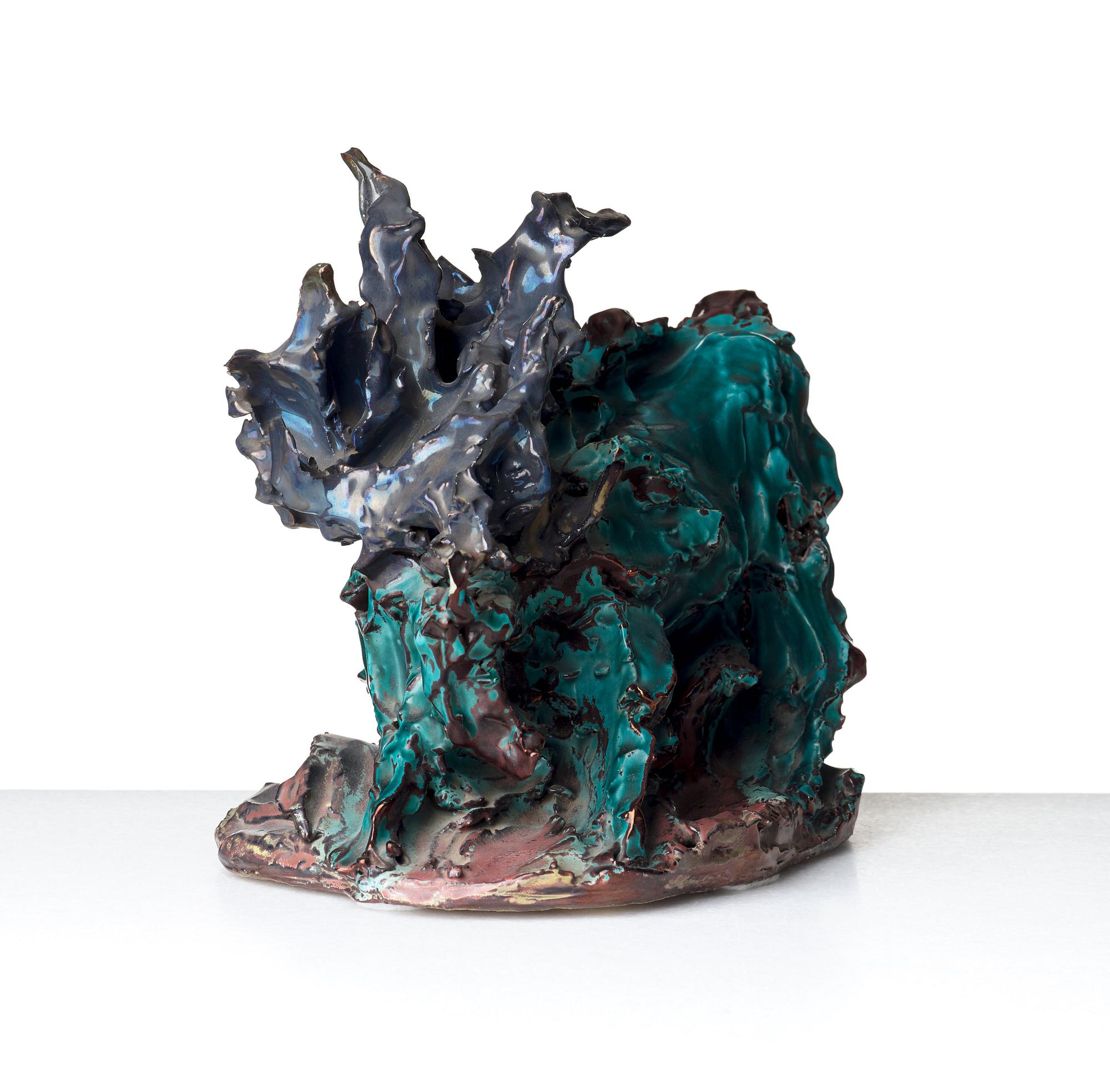

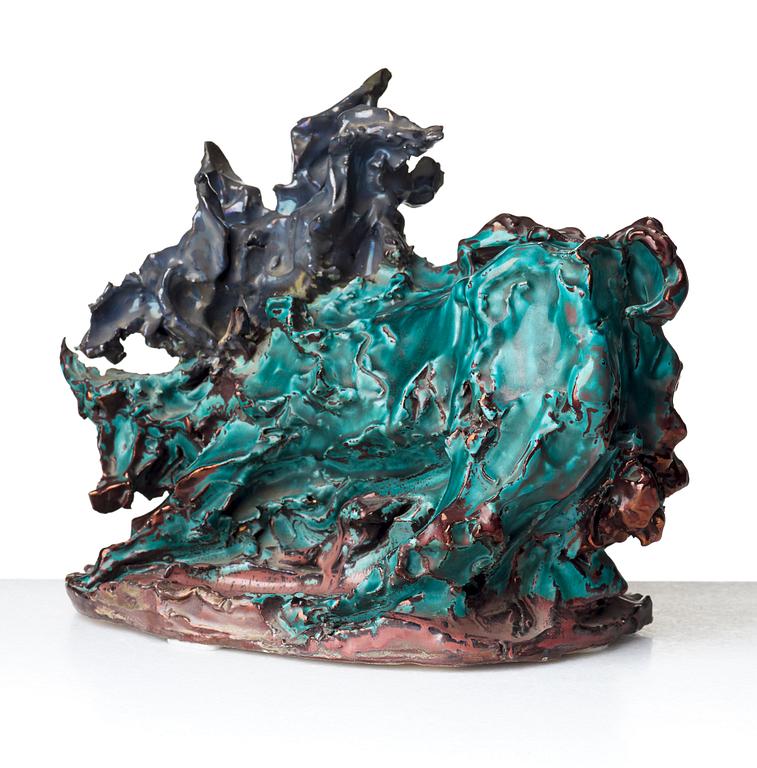

Lucio Fontana

"Senza titolo"

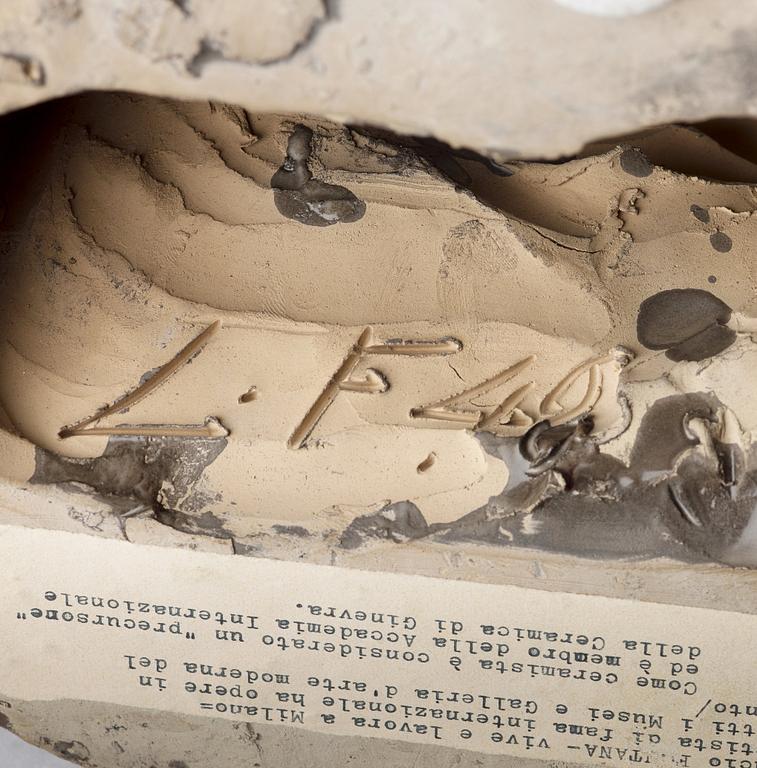

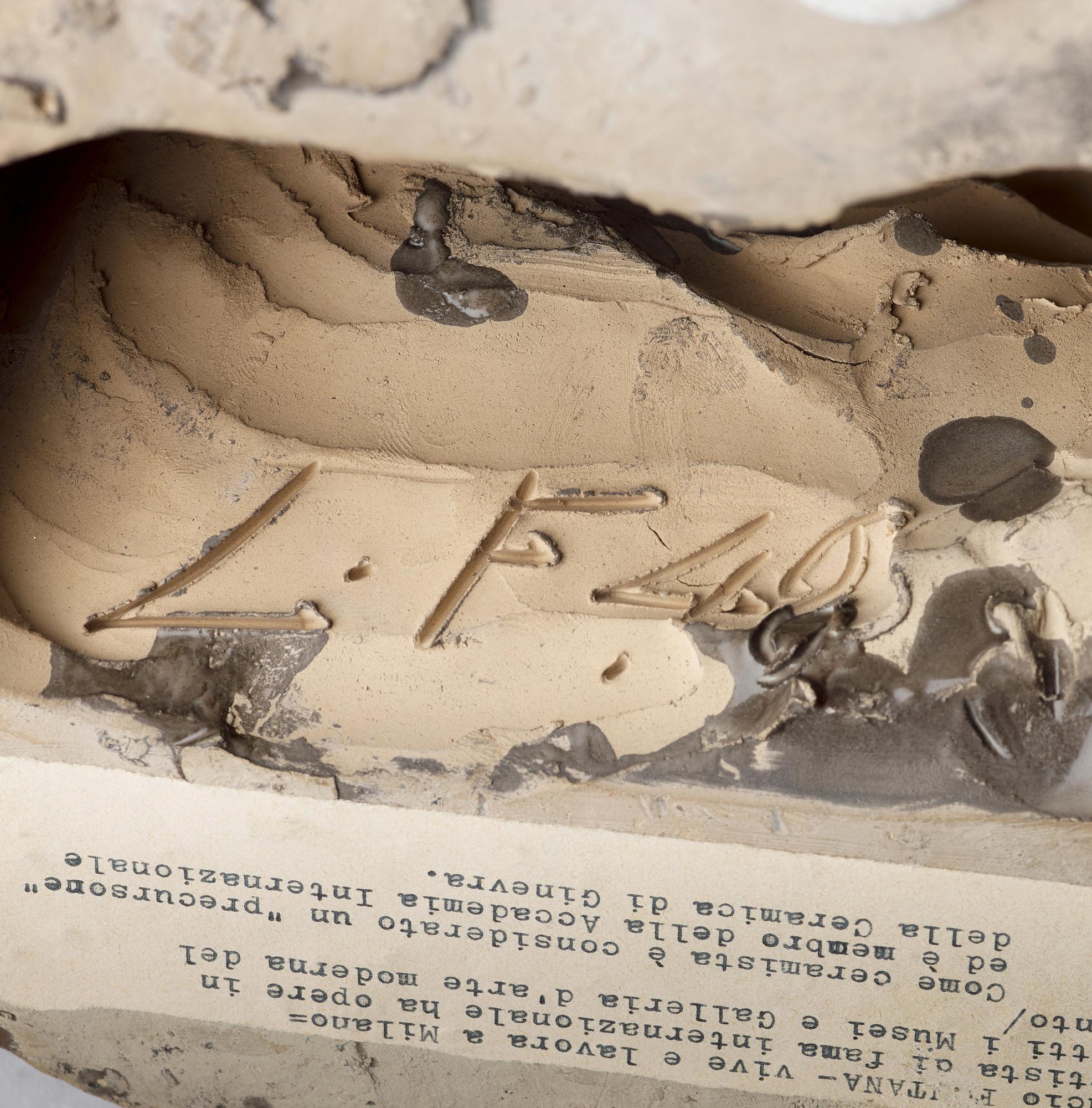

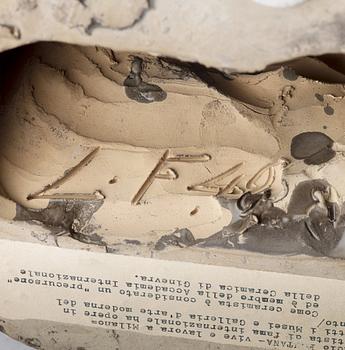

Signed L Fontana. Also signed LF and dated -48 on the inside. Glazed ceramics. Height 28 and length 34 cm. A certificate of authenticity executed by Fondazione Lucio Fontana is included with the lot.

Provenance

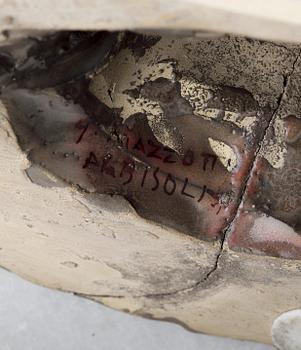

Acquired 1962 at Giuseppe Mazzotti Manifattura ceramiche, Albisola, Italy.

Private Collection, Stockholm.

More information

During the 20th century advances in science and technology captivated the West, with people following the new discoveries and inventions almost religiously. One of these people, interested in and inspired by science, was the Italian-Argentinian artist Lucio Fontana. He absorbed the new world with its radio, television and above all satellites and space exploration. Fontana’s work is clearly influenced by notions of space, light, time and parallel worlds.

Today Lucio Fontana is mostly known for his minimalist paintings with slashes and perforations, but his early ceramic work played an important role in his later paintings. In his sculptures from the 1930s and 40s he had already begun to move towards a scientific approach, with cuts and perforations being used as marks of space, light and dimensionality. This was an approach he later applied to his canvases.

Growing up Fontana had come into contact with traditional sculpture and liked to experiment as a sculptor with stone, metal and ceramics. During the 1930s he lived in France and was inspired to create expressionist sculptures – he wanted to convey emotions rather than reality. In his sculptural works Fontana returns to the techniques and traditional subjects characteristic of ceramics, such as landscapes, religious scenes, figurative and animal motifs. Fontana attempted to liberate his art from its spatial frames by creating spontaneous expressive movements through well-defined edges. In doing so Fontana highlighted the softness and the versatility of the materials he used.

Up until the 1940s Fontana lived and worked in Italy and France, but at the start of the Second World War he travelled to Argentina. It was in Buenos Aires at the Academia de Altamira that his ideas of ‘Spazialismo’ were born, which came to shape the rest of his artistic career. He created a manifesto, Manifesto Blanco, in which he encouraged artists and like-minded people to abandon traditional and academic notions of art and dare to embrace new approaches and shapes.

A significant aspect of what made him so compelling was his ability to merge sculpture and painting. His choice of forms remained varied throughout his career – from geometrical perfection to shapes that were more difficult to define. It wasn’t about the cuts or the holes in themselves, but about the process of getting there.

Fontana’s contribution to Spatialism, and the innovative forms he used, have inspired a new generation of artists to ‘think outside the box’. Lucio Fontana’s work was a product of its time, regardless of medium or technique.

“Art is eternal, but it cannot be immortal” (Lucio Fontana, The First Manifesto of Spatialism).

Artist

Up until the 1940s, Lucio Fontana lived and worked in Italy and France, but at the wake of the Second World War he fled to Argentina. In Buenos Aires at the Academia of Altamira, his idea of Spazialismo was born, a artist movement grounded by Fontana which came to define the majority of his career. In his manifesto from 1946, Manifesto Blanco, the artist challenged his peers to steer away from the tranditional and academic elements of art, urging them to include new techniques and darw to create art into the fourth dimension.

A great reasoning behind Fontana's popularity was his ability to combine sculpture and painting. His choice of forms was inconsistent during the entirity of his career, from geometirc perfections to more undefinable forms. It didn't matter so much about the end result, but rather the process it took to get there. Fontana's art was a product of its time, no matter the medium or technique.

Already in 1947, Fontana began working with the concept Concetto Spaziale. A few years later his Pietre series was added where he seemlessly combines sculpture and painting by applying thick layers of paint on a canvas and thereafter adding a collage of colourful glass chips. Not long after that Fontana entered a period with Buchi, where he made holes in the canvas to break up the two dimensionality of the composition in search for the space behind the painting. At the end of the 1950s he began his work with Tagli, whereby he sliced his canvas which continuously applying his Buchi technique, a style which he continued with up until his death in 1968. Through Concetto Spaziale, Fontana managed to blurr the lines between painting and sculpture.

His first Tagli was created at the end of the summer and early autumn of 1958 when Fontana was almost 60 years old. His canvases were filled with small diagonal incisions which he grouped together. Fontana experimented with size and form, and with time the slices became less and more powerful. To reach the right effect, Fontana was incredibally precise with the surface of the canvas, coating it first with a matt, often water based, monochrome colour. His pieces with only one slice are marked as "Attesa" and the canvases with multiple slices are marked with the plural form, "Arrese". The meaning "expectation or hope" gives an additional dimension to the work. Fontana covered the back piece with "telleta," strips of deep black fabric to create the illusion of an empty space behind the canvas. In Tagli, destruction and creation merge. Every slice is formulated through a definitive and irreversable gesture. Every action which results in a wound upon the canvas simultaneously allows for a new sculptural perspective out into the black neverending space behind the canvas. Fontana's artistic journey with Tagli and Buchi happened correspondingly with the 1960s space race.

"As an artist, when I work with one of my perforated canvases, I have no desire to create a painting; I want to create an opening for space, to give art a new dimension, to bind it to the cosmos, as it endlessly continues beyond the boundaries of the painting. With my innovation of holes drilled through the canvas in repeated formations, I do not wish to decorate a surface, but rather to break up its dimensional limitations. Behind the perforations lies a newfound freedom for interpretation, but also, just as inevitably, an end to art." (Lucio Fontana, 1966)

Fontana came and had several exhibitions in Sweden during the 1960s. One of his greatest admirers was the gallerist Pierre Lundholm at Galerie Pierre in Stockholm who not only arraned exhibitions in 1964, 1967, and after Fontana's death in 1971, but also stored and sold Fontana's work. Fontana even managed to exhibit at the Swedish French Art Gallery in 1965 as well as have a large exhibition at Moderna Museet in 1967 in Stockholm through the initiative of Pontus Hultén. His paintings were admired by the most asteemed collectors, and with the wider public, his works were preceived as bizzar and incomprehensible. Today Lucio Fontana is praised for his art that stood as a testament beyond his time.

Read more