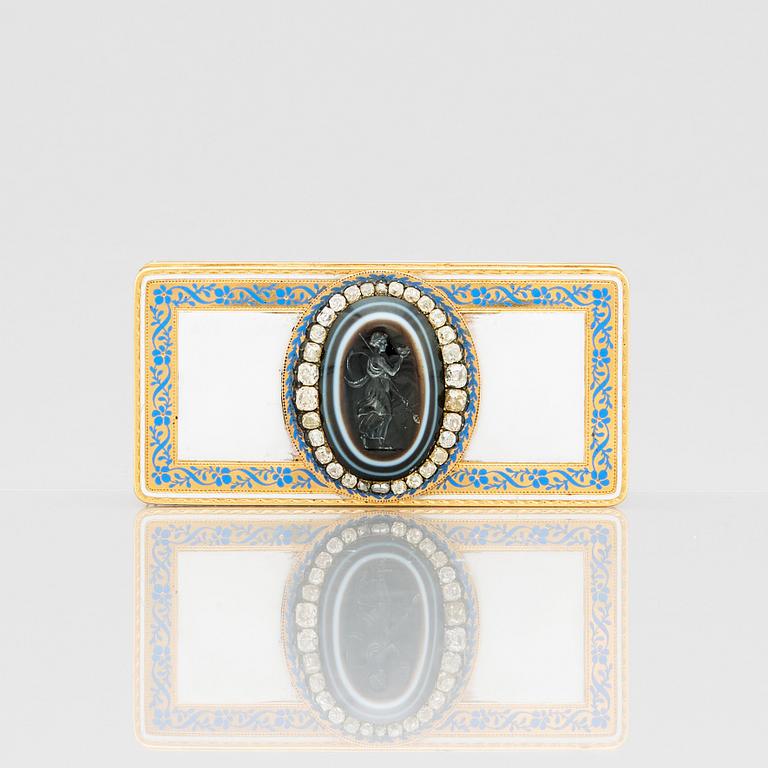

A jewelled gold and enamel box, Otto Keibel, St Petersburg 1799, Empire

Rectangular, decorated on all sides with panels of white enamel framed by flowers in blue enamel, the lid set with an agate intaglio mounted in a frame of 30 old cut diamonds.

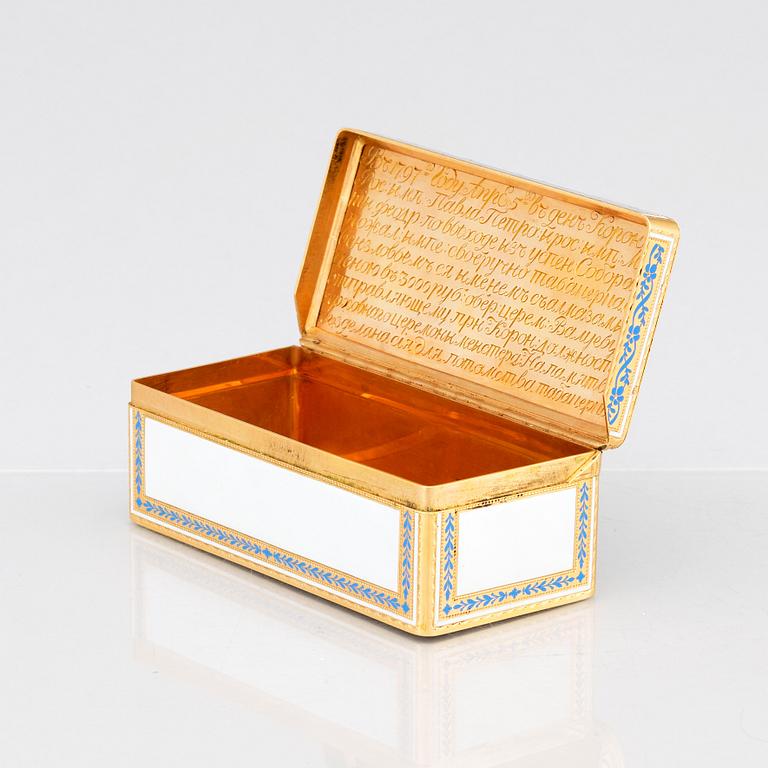

The inside struck with makers initials, 76 standard, year and assay master Aleksander Ilych Yashinov. The inside of the lid set with a later engraved gold sheet indicting another box presumablly gifted 1797.Length 9,5, width 4,5, height 4 cm, weight 217 gram. Original red leather case.

Provenance

Swedish private collection.

Thence by decent.

More information

Otto Keibel was one of the first in St. Petersburg to design empire style boxes of which the auction box is an early example.

However, the engraved gold sheet embedded in the inside of the lid has nothing to do with this box. Not only does the text not quite fit, the box is clearly stamped 1799 while the text refers to the coronation of Paul I in 1797. According to the engraved text, the box would also have the emperor's monogram in diamonds, be worth 3,000 rubles and be from the emperor's own hand given as gift to the Chief Master of Ceremonies Valuev.

According to Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, who has researched the Russian reward system, the entire text is an impossibility. The emperor never "of his own accord" gave a gift to a subordinate. These were official gifts whose design and value were tied to a set of regulations. A gift was always presented by a high representative of the court - perhaps the minister of the court and it was legion that a recipient rarely received his grace immediately, but it could take a year, but the recipient immediately received a certificate of the gift.

Inscriptions never appeared on these favors, which could also be seen as disguised monetary gifts. The recipient had every right to return his box to the imperial cabinet, which was the place where the whole process was handled and then you got the full amount the box was worth. If the gift was worth 3,000 rubles, as it says, it was a considerable sum, by comparison a general had about 10,000 a year in salary.

Inscriptions on gifts are thus secondary and were put there by the recipient or by later generations. In this case, the original box does not remain, but someone has wanted to preserve the memory of the event by moving the text plate to another box, the one that is now being sold.

Bukowskis would like to thank Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm for the information.