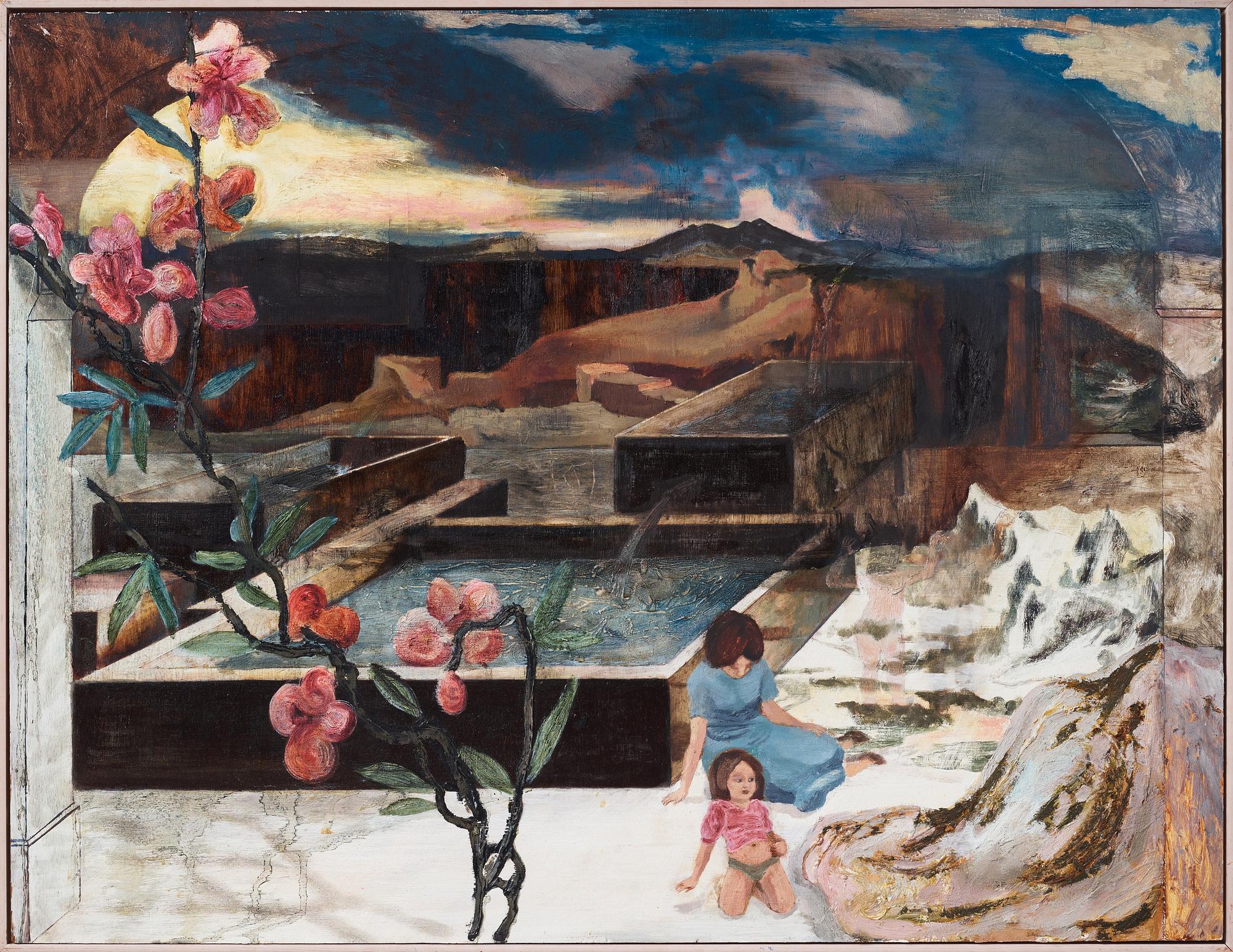

Mamma Andersson

"Objekt"

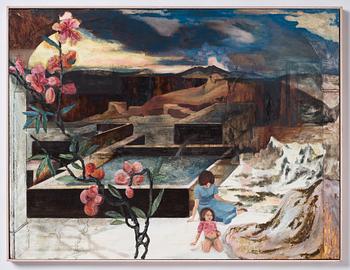

Signed Mamma Andersson and dated 2000 verso. Oil on panel 76 x 100 cm.

Provenance

Galleri Kavaletten, Stockholm, 2000.

Stockholms Auktionsverk, Moderna Kvalitén, 25 April 2007.

Private Collection, Stockholm.

More information

Mamma Andersson’s painting ‘Objekt’ was executed in the year 2000, when the millennium was fresh and exciting. That same year she exhibited the painting at Galleri Kavaletten in Stockholm. Could she have even imagined that twenty-five years later she would be considered one of Sweden’s most important contemporary artists, be represented by galleries in three countries, and that her work was to fetch record prices at auction?

The first decade of the 2000s was more or less a golden age for Mamma Andersson. She was productive, succeeding in creating some of her very best paintings, whilst at the same time being represented at major art fairs and biennales. The big breakthroughs came in quick succession, including being awarded the Carnegie Art Award in 2006 and a solo show at Moderna Museet in 2007.

In her long artistic career she merges several classic genres such as still life, landscape painting and interiors, yet her expression remains highly contemporary. The paintings are created as a kind of painterly collage, where image fragments, stories and motifs are joined together in multiple layers. Time and space are fractured, forming new, completely independent worlds.

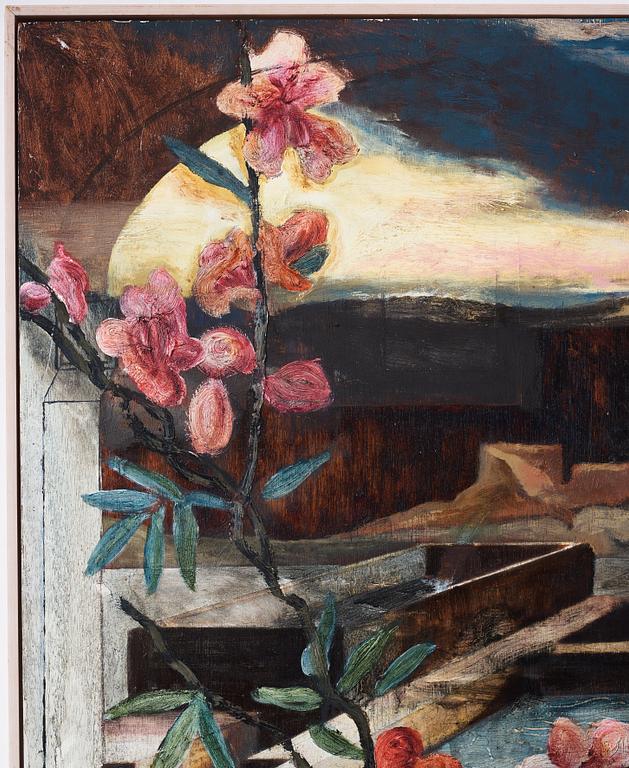

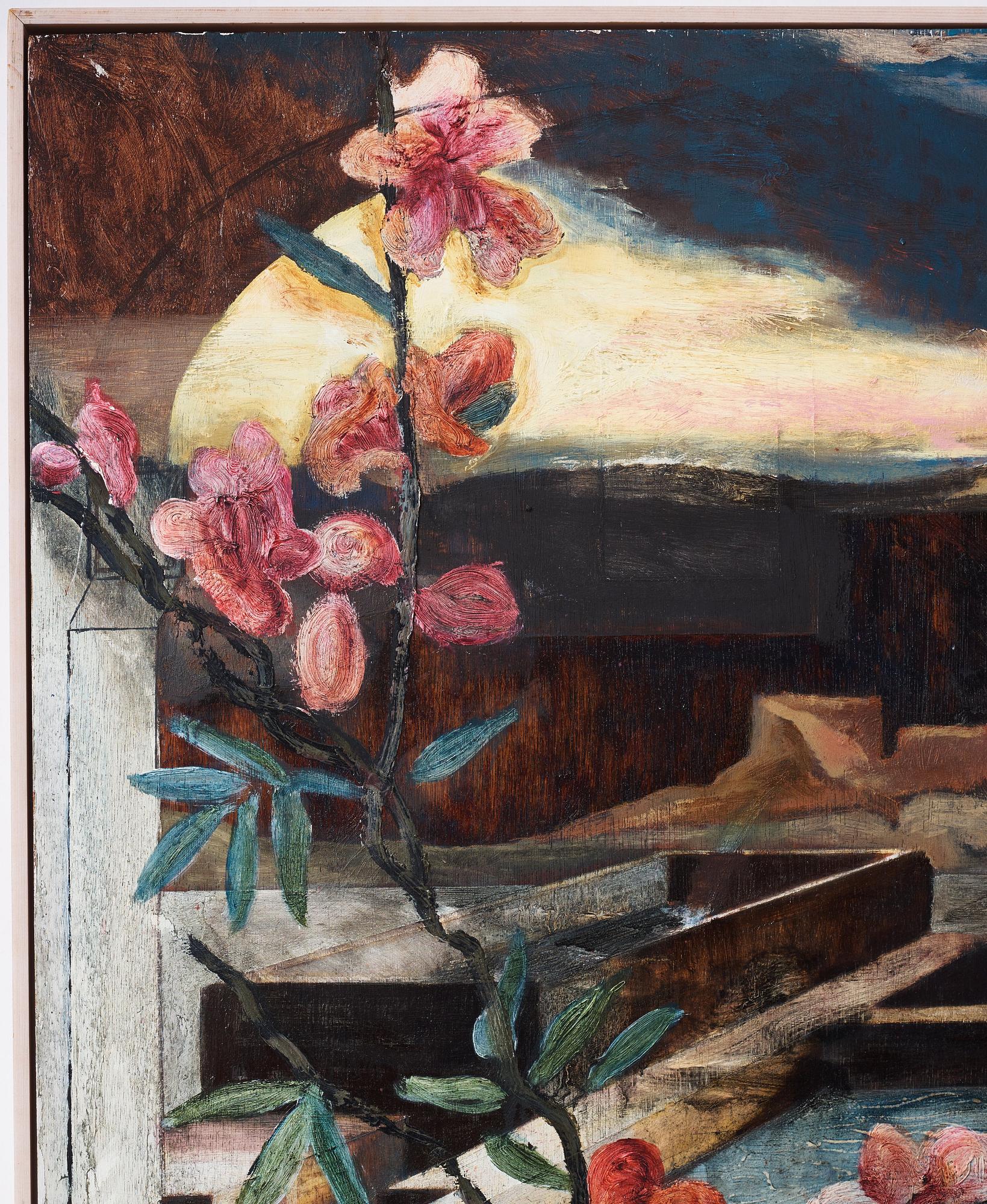

The architectural elements in ‘Objekt’ consist of the arch in the painting’s foreground, but also of the angular pools in the centre of the painting. The dramatic, dark landscape in the background is contrasted with an intimate family scene, where a mother, wearing a blue dress, is seated on the ground with her head bowed. Her child is looking away towards an area of snow-capped mountains in the bottom right-hand corner of the painting. Diagonally across the picture the artist has placed a flowering cherry blossom branch, not unlike those often seen in Japanese woodcuts. In Japan the cherry blossom is a symbol of the fleeting nature of life and a reminder to appreciate its beauty whilst there is still time. Perhaps it is also a reminder to the mother of all that will be missed if she takes her eyes off her child during those first hectic years when they develop so quickly.

The turned-away gazes are a recurrent theme in Karin Mamma Andersson’s paintings. According to the artist the paintings are peopled by characters with their backs turned to the viewer, or with their faces turned away, because otherwise they would become too dominant in the painting. In an interview for the exhibition catalogue to her solo exhibition at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark (2021) she ruminated on precisely this aspect: “[…] ‘You once said that a face steals energy from the rest of the painting.’

‘Exactly. I guess it’s about a certain discomfort. As soon as a figure has its face turned to you, your gaze stops there. That’s just the way it is. […] A gaze is very dominant, and I often feel a bit bothered by it. I think it comes down to shame. When I do paint faces, they are often the faces of dolls. It’s easier to meet an unreal person’s gaze, because it’s not an actual gaze. It may be hindsight, but I have often wondered why I shy away from the face. Maybe it’s just because it seems disturbing to me.’”