A blue and white bowl, Mingdynastin, Transition/Chongzhen period circa 1643.

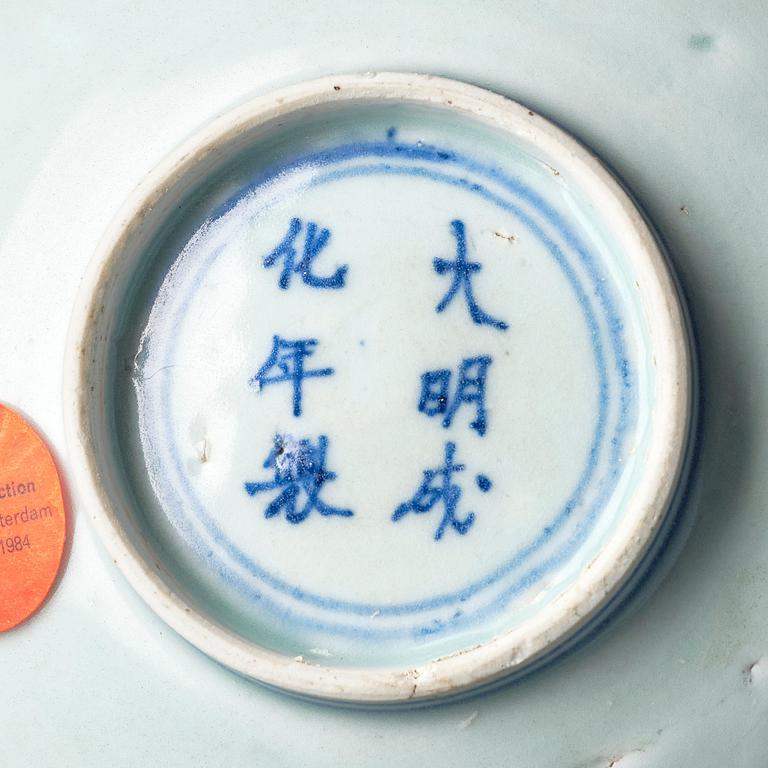

The shallow bowl is decorated on the interior with a central medallion containing the white hare seated beneath an osmanthus tree, all below the rim encircled by a key-fret band. The exterior is decorated with three small insects and the recessed base is inscribed with an apocryphal Chenghua mark. Diameter 18 cm.

Small chip to footrim. Fritting.

Provenance

The ‘Hatcher Cargo’; The Historical Importance of a 17th-Century Ship. The wares discovered in the early 1980s in the ‘Hatcher Cargo’, named after the Captain who made the discovery, now serve as important benchmarks for the dating of 17th-century Chinese porcelains. The cargo of the ship included some 25,000 pieces of porcelain, mostly blue and white wares from Jingdezhen, but also examples of celadon wares, Dehua wares, polychrome wares and provincial blue and white wares. Several thousand of these were sold in a historic sale at Christie’s Amsterdam in 1984, from which all of the 'Hatcher’ pieces in the Curtis Collection were purchased. (fig. 1) Because no trade records exist to identify the ship and hence the destination to which it was headed, scholars needed to use a combination of deductive reasoning and knowledge of the porcelain trade at the time to date the wares salvaged from the vessel. While the Dutch East India Company (VOC) used Chinese junks to transport cargos from Taiwan to Batavia, the diversity of the wares in the 'Hatcher’ wreck indicates that the ship was probably headed for wholesale markets in Batavia or Bantam.

Exhibitions

Compare lot 3515, Christies, 16 Mar 2015.

Literature

Colin Sheaf and Richard Kilburn, The Hatcher Porcelain Cargoes, The Complete Record, London, 1988, p. 30) Sheaf and Kilburn take a step-by-step process to deduce that the ship most likely sunk between 1643 and 1646. The inclusion of two covers for ovoid jars (similar in shape to the lot 3513) bearing inscriptions and a cyclical date corresponding to the spring of 1643 indicates that the vessel sank no earlier than the spring of 1643. The authors also note that because of the internal unrest in China at the time, trade was significantly disrupted at the fall of the Ming dynasty and studies of VOC records show that by 1646 the Manchus were preventing the free movement of trade and shipments out of Jingdezhen. The authors conclude that it is therefore very likely that the Chinese junk known as the 'Hatcher Cargo' must have sunk sometime in the years between 1643 and 1646. In her article, “Transition Ware Made Plain: A Wreck from the South China Sea" (Oriental Art, Summer, 1985), Dr. Julia Curtis offers an extensive and in-depth look into the significance of this find, noting that the wares auctioned by Christie’s should “enable students of Chinese ceramics to view the wares of the Transitional period as a whole; the varied nature of the load provides ceramicists with a comprehensive view of Chinese porcelain production in the 1640s. The 'Hatcher Collection' also provides insight into the origin of styles in the era of Kangxi (1662-1722). The numerous kraakwares in the load, many painted with scenes in typical Transitional rather than Wanli style, should enable students of the ware to differentiate later kraakware from its earlier counterparts.” (p. 161) The kraak-style dishes in the cargo (see lot 3521) also proved that such wares were traded, if not produced, until the end of the Ming dynasty. While other vessel shapes in the cargo such as beakers and rolwagens, previously made for the Chinese market but now popular in the West, were decorated in a contemporary style, the dishes included were predominantly all kraak style. Other wares presumed to be contemporary with the wreck include small jars and vessels decorated in a distinctive landscape style (see lot 3523), small items with figural decoration, as well as small dishes boldly painted with scenes derived from narratives or printed sources (see lots 3516, 3525). The cargo also included shapes such as kendis, presumably intended for the near-Eastern market (see lot 3515).

More information

According to Daoist legend, a jade-white hare or rabbit lives on the moon, grinding the elixir of immortality with a pestle and mortar. The elixir was believed to have been stolen from the archer Yi by Lady Chang-E, who fled with it to the moon. However, a Buddhist story provides another explanation of how the rabbit came to live on the moon. The Buddha arrived in a forest, exhausted and hungry after many days of traveling. All the animals came to him bringing the foods that they usually gathered for themselves. The rabbit intended to bring fresh green grass and leaves, but when he found them, he ate them himself. The rabbit was consumed by guilt and going to the Buddha admitted his folly and offered that the Buddha could eat him instead. The Buddha was so touched by this gesture that he bestowed upon the rabbit the gift of eternal life on the moon. Rabbits are therefore associated with long life.