Lynn Chadwick

"Maquette I Elektra", no 579

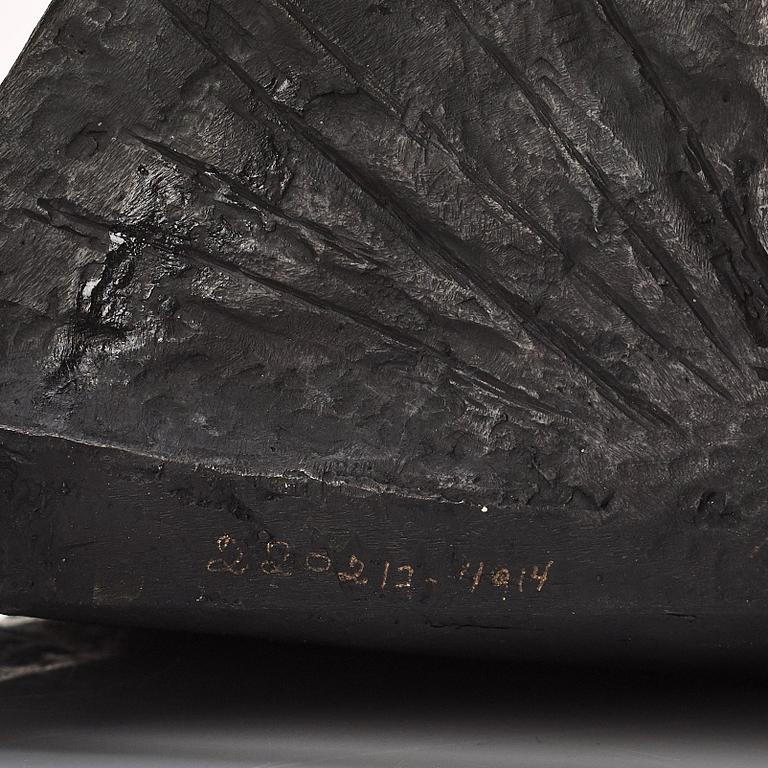

Signed Chadwick, dated -69 and numbered 579 2/4. Bronze, height 65 cm. Stamped with the foundry mark Morris Singer Founders London.

Saleroom notice

Litterature:

Nico Koster & Paul Levine, Lynn Chadwick: The Sculptor and His World / The Artist and his Work, 1988, another cast illustrated p. 97.

Dennis Farr and Eva Chadwick, Lynn Chadwick: Sculptor, Oxford 1990, p. 234, no. 579, illustration of another example p. 235.

Provenance

Court Gallery, Copenhagen, 1970, cat no. 21 in the exhibition catalogue.

Thence by descent to present owner.

Exhibitions

Court Gallery, Copenhagen, "Lynn Chadwick - bronzes 1959-1969", 1-30 May, 1970, cat no. 21 in the exhibition catalogue.

Literature

Nico Koster & Paul Levine, Lynn Chadwick: The Sculptor and His World / The Artist and his Work, 1988, another cast illustrated p. 97.

Dennis Farr and Eva Chadwick, Lynn Chadwick: Sculptor, Oxford 1990, p. 234, no. 579, illustration of another example p. 235.

More information

Lynn Chadwick’s characteristic sculptures are immediately recognisable as his. They have their own distinct look to them and form a unique artistic idiom. Majestic, mysterious strangers, hardly resting – more likely watching, they awaken associations and fascinate with their geometrically simplified forms and awkwardly draped cloaks.

Chadwick made his debut on the British art scene soon after the Second World War alongside a new generation of artists. Europe was in ruins and the world was in shock, having just witnessed the horrors of war, genocide and the effects of the atomic bomb. Chadwick served in the war as a pilot for the R.A.F. Yet as a young man he had already wished to dedicate his life to art. His parents’ disapproval made him compromise in his career path, and he decided to study architecture. Before the war he worked as a draughtsman in an architects’ office. Chadwick had no formal art education and perhaps it is possible to discern the strict geometry of architectural drawing in his artistic practice. After the war he was filled with the desire to create, to make something new. Chadwick recounts: “But some of us felt after the war that we had to make something and that painting was exhausted as far as this attempt to make something was concerned. Actually, we didn’t – at least I didn’t – think of sculpture as such. We thought of construction, of building with our hands”. It did, however, take some time before he dared to go the whole way and be an artist, and so for a few years he worked successfully as a designer and an interior architect. During the late 1940s he made a living from designing, amongst other things, display stands, furniture and wallpaper patterns, whilst simultaneously working on his art.

It was with the Venice Biennales of 1952 and 1956 that Chadwick had his major international breakthrough. Since then he has been considered as one of the most important artists of the British postwar period. The expression in Chadwick’s sculptures is highly interlinked with his working methods. Practically self-taught, he invented his own techniques. The method has been described as a kind of three-dimensional drawing with iron rods, where Chadwick first curved and shaped the rods into the desired form and then welded them together. Next he filled the sections that were to be solid. In some sculptures he used metal plates, which created the impression of ‘metal skin’. It wasn’t until the end of the 1950s that he also began casting in iron. Chadwick placed great significance on the sculptures’ patina and worked a lot with the structure and nuances of colour in the surfaces.

He further recounts: “I think that my personal idiom came through my technique, really, and because I worked in this way these images came this way and I couldn’t have done it any other way. I couldn’t have painted this and I couldn’t have carved this in wood because it would have come out quite differently. I wouldn’t have been able to do it. Everything is because of, shall we say, the limitations of my technique.”

The triangle in different executions is the fundamental geometric shape in Chadwick’s art, sometimes joined together to create rectangles. This form, placed vertically or diagonally (rarely horizontally), constitutes the framework of the sculptures and creates their formal tension. The artist suggested himself that the triangle was to be regarded as the simplest outline of a human or animal figure, and that it was from this shape that the body was created. He emphasised how he always began from the human in his art, as he explained, “I shall never neglect humanity. Even in my most abstract figure ‘The Pyramids’ I took man as a starting point… The stars can be seen as heads with a single eye and the pyramids can begin to suggest a figure or beast”.

In contrast to many of his contemporary sculptors, inspired by ethnographic or classical art, Chadwick found much of his inspiration in modern architecture.

The object in the auction, Maquette I Elektra, from 1969, is an exquisite example of Chadwick’s late 1960s production. At this time he had returned to his human-like figures, after a period in the 60s when he experimented with more minimalist and abstract work as well as with techniques such as assemblages of found objects. In this phase he began using the representational geometric forms of the triangle and the rectangle as symbols of man and woman. Chadwick has himself never explained or given any interpretations of his sculptures. This leaves the viewer free to let their own imagination and associations wander around these powerful and mysterious figures.

Artist

One immediately recognises Lynn Chadwick’s distinctive figures. They have their own visual language, with their formal language resembling no other. These majestic beings appear enigmatic, hardly at rest – rather vigilant. With figures which draw upon simplified geometric forms with sharply draped cloaks, these sculptures evoke associations and fascination.

Chadwick joined a new generation of artists which all debuted on the British art scene shortly after the World War. Europe was in ruin, and the world was arrested in great shock after having experienced the trials and tribulations of war. Chadwick himself was an active participant, having worked as a pilot in R.A.F. Already in his younger years Chadwick was sure that he wanted to direct his career into the world of art, yet his parents disapproved, and thus he was forced to compromise and thus began to study architecture. This is why Chadwick found himself working at an architectural firm before the onset of the war. It can therefore be argued that it is thanks to his architectural training that his sculptures exhibit such a strong geometrical aura. The aftermath of the war left Chadwich longing to create and to achieve something new. Yet it took a while for him to find the courage to fully commit, and thus he continued to have a successful career as a interior designer. In the 1940s Chadwich made a living by designing exhibition stands, furniture, wallpaper simultaneously as he began his career as an artist.

It was thanks to the Venice Biennale of 1952 and 1956 that Chadwick gained international recognition and has since then been thought to be one of the most important artists within the British post-war era. The expression in Lynn Chadwick's sculptures is deeply linked to his methods. For the most part Chadwick is solely self-taught, with his technique having been described as a three-dimensional metal drawing. Chadwick would bend and shape of rods into desired forms, then weld them together, after which he filled in the areas that were to be solid. For various sculptures he utilised metal plates, giving the impression of a “metal skin”. In the 1950s Chadwick began experimenting with bronze. Chadwick placed great emphasis on the patination of his sculptures, meticulously working on surface texture and color nuances.

The triangle is the overarching form in Chadwick’s art, which is sometimes combined with the rectangle. This form, often placed vertically or diagonally (never horizontally), forms the backbone of the sculpture and establishes the formal tension. The artist himself has declared that the triangle is the most stripped-down, basic form of the human body, and it is from this shape people are constructed. He had always clearly expressed how his primary inspiration lay always with the human form.

In contrast to many of his contemporaries who were inspired by ethnographic or classical art, Chadwick found inspiration from modern architecture. The artist never explained the symbolism or meaning behind his sculptures, rather he has left his blank to allow the viewer to form their own interpretations as to the reasonings behind these powerful, enigmatic figures.