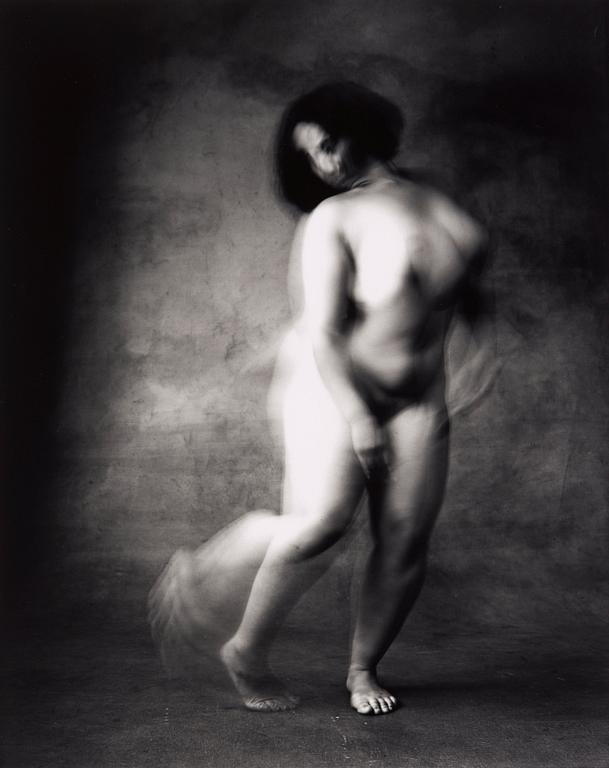

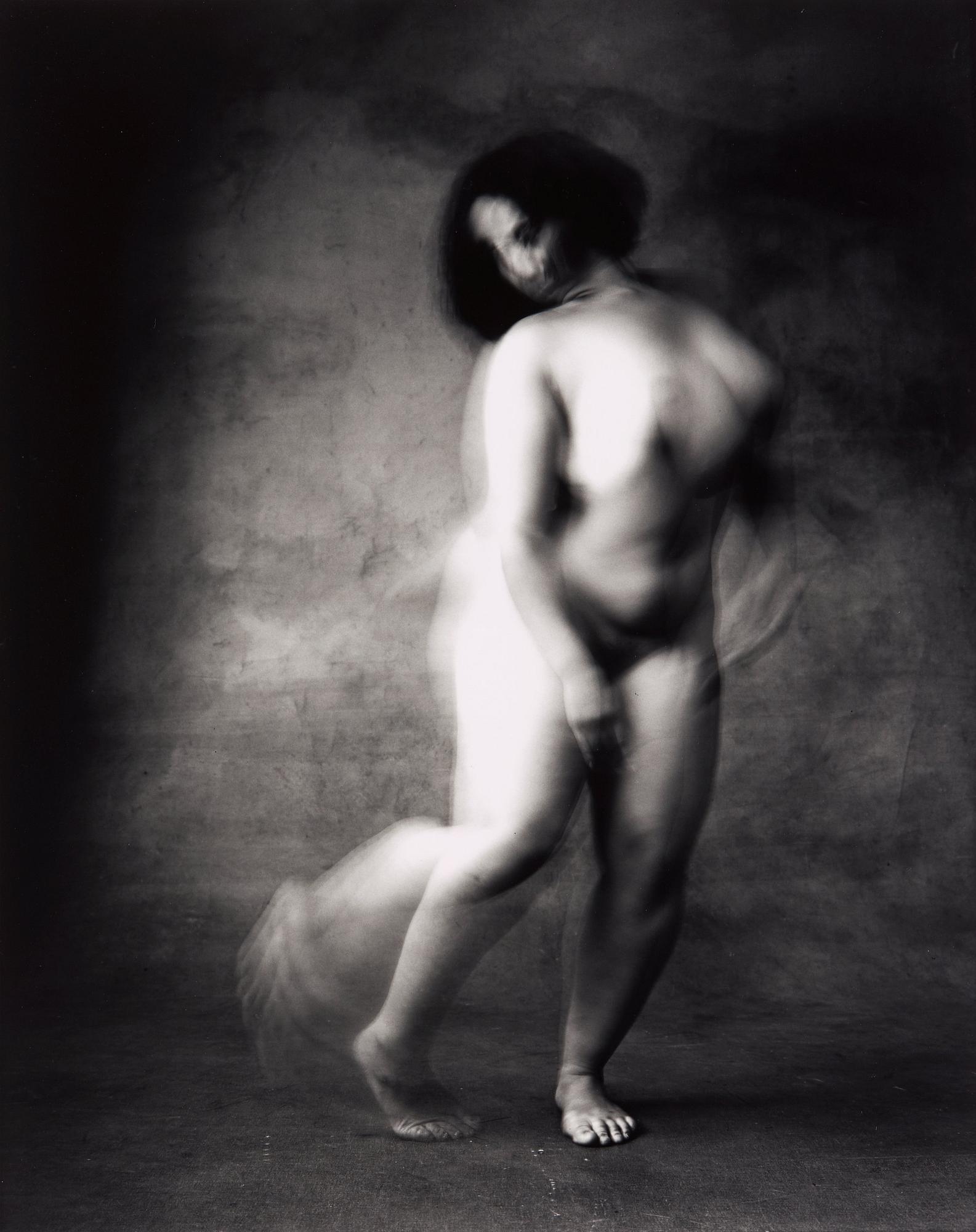

Irving Penn

"Alexandra Beller, New York", 1999.

Signed Irving Penn and dated January 2000 on verso. Also stamped "Photograph by Irving Penn copyright 1999" on verso. Edition 20. Vintage. Selenium-toned gelatin silver print, bildyta 48 x 37.5 cm. From the "Dancer" series.

Literature

Irving Penn e.a, "Dancer", 2001, illustrated fullpage pl. 24.

More information

Serien med bilder på dansaren Alexandra Beller, ”Dancer”, blev Irving Penns sista stora konstnärligt sammanhållna projekt. Resultatet är en rad bilder, alla olika, några med större skärpa och kraft i uttrycket andra mjukare med mer poetisk höjd. Hans personliga engagemang framgår tydligt i bilderna. Just auktionens bild har ett mycket levande och spännande uttryck där Penn har lyckats fånga flyktigheten i Alexandras rörelser samtidigt som skärpan är inställd på hennes fötter. Bilden betraktas som en av Dancer-seriens bästa bilder. Fotografierna varierar i storlek, auktionens bild tillhör det större formatet. Senare (2001) publicerades även boken ”Dancer” där hela sviten finns samlad.

Två saker som spelar roll för ett specifikt konstverks betydelse är dess historiska kontext och den berättelse som kan kopplas till verket. I det här fallet är bägge dessa markörer tydliga -serien Dancer markerar avslut på ett stort konstnärskap och i boken med samma namn har Alexandra Beller själv fått berätta om mötet med Penn och känslan av att stå framför hans kamera.

"Having never modeled nude before, my first session with Mr. Penn was an anxious and uncomfortable event. Penn's gaze made this both more and less relaxing. His respect, his integrity, his incredible calm were, of course, sources of relief to me; his intensity of focus, however, was like an X-ray, so any comfort gained by my superficial body evaporated quickly in the soul-searching depth of his eyes. His eyes were like no other that I have seen; keen does not begin to cover it. But after the first session, we scheduled another, and then another and another and eventually, without premeditation, the collection was born.

If one were pressed to describe the sensation of sight to someone born without it, where would we begin? I believe, from watching him watch, that his sense of sight was simply different from ours. He would just watch me, allowing me to dance, saying only one of the two words he generally spoke to me: "Slower." I would continue to dance, slower. Then I would hear "stop." And I would stop. So, dancing, painfully slowly, and stopping, we would find a place to begin. Once I had stopped in a place, a shape, the architecture of a picture, he would give me tiny bits of information: "Look up," "pull your right shoulder back," "Straighten your left leg." Those tiny bits of direction yielded enormous resonance for me; I would feel, as if a curtain had parted, the emotional moment we were seeking. The vessel would fill with life. The look upwards, the opening of the shoulder revealed desire, surrender, fear, rebellion, authority, flirtation, etc.

Having trained my body for so long to sense both the past and the present through the skeleton, the muscles, the organs, the skin, his directions were like lasers, carving out evocative emotional pictures from the neutral self. We stayed neutral, socially, with each other, preferring to find this near-silent dialogue, this almost psychic connection of shape, thought, character and feeling. It remains the quietest, and one of the richest, collaborations, I've experienced."